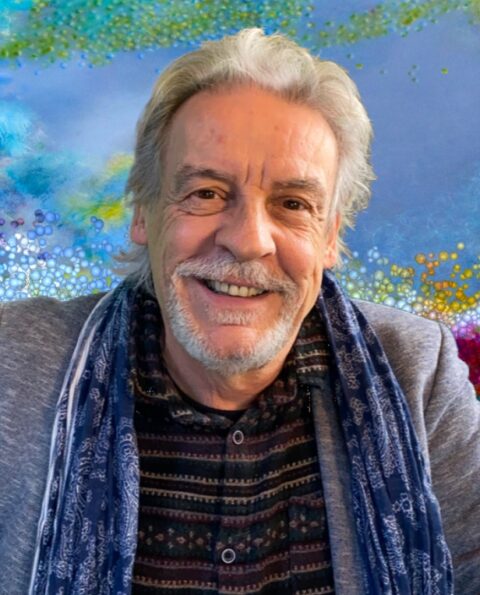

Pau Waelder

A contemporary artist, developer and an interaction designer, Ronen Tanchum has developed a body of work that explores the representation of natural phenomena and our perception of reality as it is mediated by the entertainment industry and digital media. At a time in which the attention economy fosters a visual culture based on spectacularity and evasion to fantasy worlds, his work draws attention to how digital technologies, from 3D modeling to machine learning, reshape our perception of the world around us.

In his long-time collaboration with Niio, Tanchum has presented numerous artworks that we are now gradually collecting in a series of solo artcasts, offering a glimpse into the many facets of his artistic practice. In this interview we dive a little deeper into the main subjects of his work.

Ronen Tanchum. Particle Forest, 2022

Your work is characterized by an interest in nature and natural phenomena, particularly the behavior of fluids. This is obviously related to your work in the film industry, but if you look at it from the perspective of your artistic research, what does nature as a subject and fluid mechanics as a tool bring to your art practice?

Yes, this is the DNA of my artworks and what they convey. Ever since I learned computer graphics for the first time and had access to 3D software, some 20 years ago –when I was 16– I was trying to learn the software and to make the computer create something that is believable. This notion always brought me back to study the real world. So, I had to carefully observe the world around me, from the little imperfections of a corner of wall that needs to be reproduced synthetically, to complex natural behaviors that need to be recreated digitally in order to create realistic content. This required a lot of work, but additionally it was not only about making the recreation realistic, but rather a hyperreal, exaggerated reality that made the content visually attractive and engaging.

“Instead of starting with nothing (a blank canvas) and adding on to it, I start with a lot of chaotic data and I shape it little by little, tweaking the algorithms, refining, and testing again and again until I reach a result that I’m satisfied with.”

During my whole career as a specialist in 3D technologies and simulations I had to recreate a lot of natural effects synthetically, so that they are used in key moments of Hollywood films, where reality is presented as a spectacle. For instance, an effect of clouds covering the sky and then dissipating, that has a narrative role in the film, so it has to be created in a way that looks as realistic as possible while also supporting the narrative. I worked with many natural phenomena, like waterfalls and tornadoes to rain, snowfall, and fire, and I found that the possibility of reproducing these phenomena synthetically within the machine was fascinating. So I continued to explore these technologies while also playing with the boundaries of what is real and what is not, and the way that natural forces and elements behave. Exploring these techniques led me to a deep understanding of the human role in the synthetic reproduction of nature, and how we do not simply reproduce what we observe, but we interpret it. We play with it, we make it more expressive, we manipulate the behavior of the elements, time, and natural forces to give a dramatic quality and visual appeal to something as mundane as a splash of water from a bucket on the floor.

So my artistic practice has focused on exploring the creative possibilities of reproducing natural elements and landscapes, flora and vegetation synthetically through different technologies, programming languages, and mediums. Using computer algorithms to create these simulations of nature is quite a challenge in itself, because instead of starting with nothing (a blank canvas) and adding on to it, I start with a lot of chaotic data and I shape it little by little, tweaking the algorithms, refining, and testing again and again until I reach a result that I’m satisfied with. I find this practice very challenging and encapsulating in ways that I could never do with a pen, paper, and ink, or with a canvas, a brush, and paint. I design systems that have a life of their own once the program starts running, so there is also a sense of creating a situation with a certain degree of control, and also letting go.

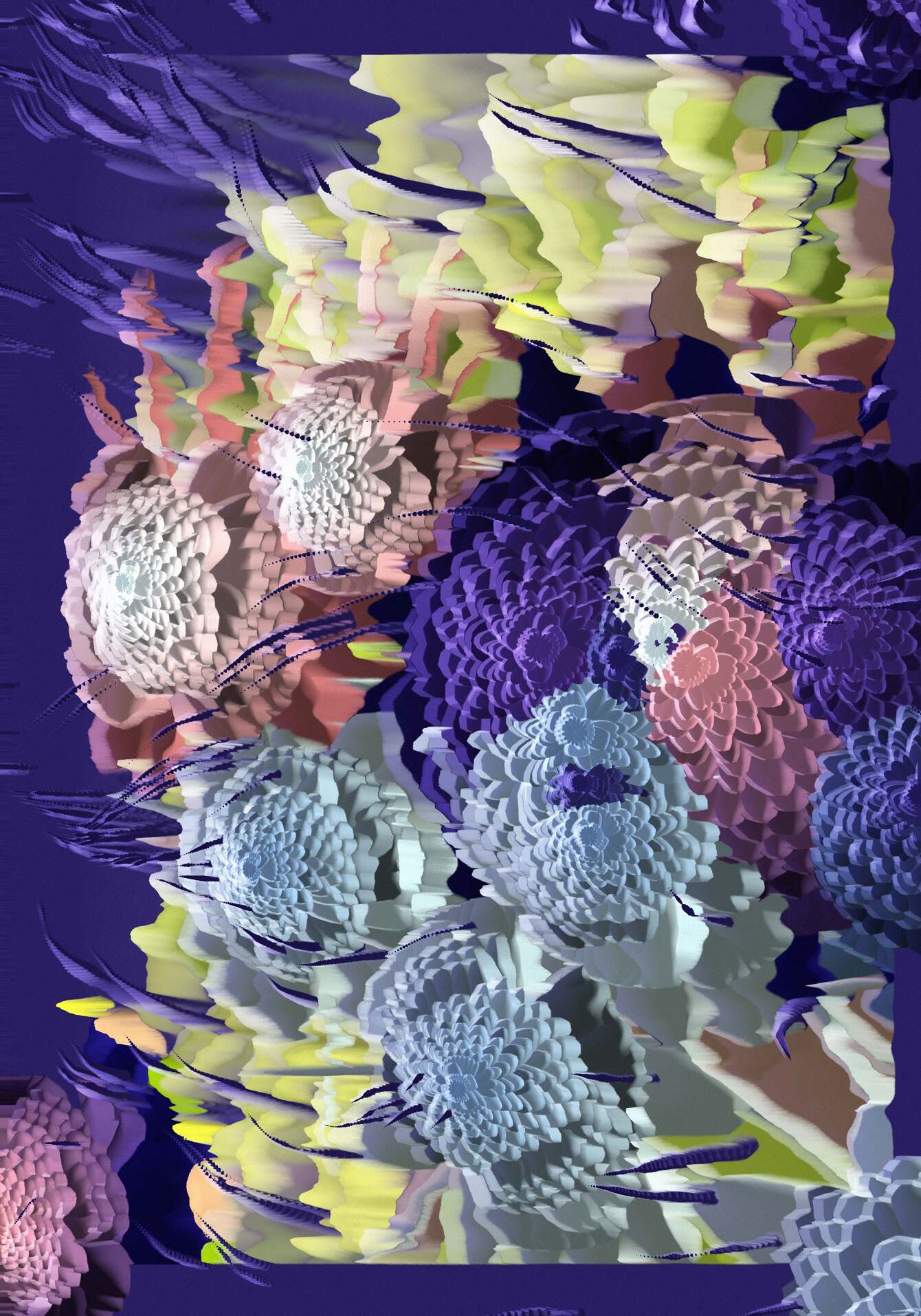

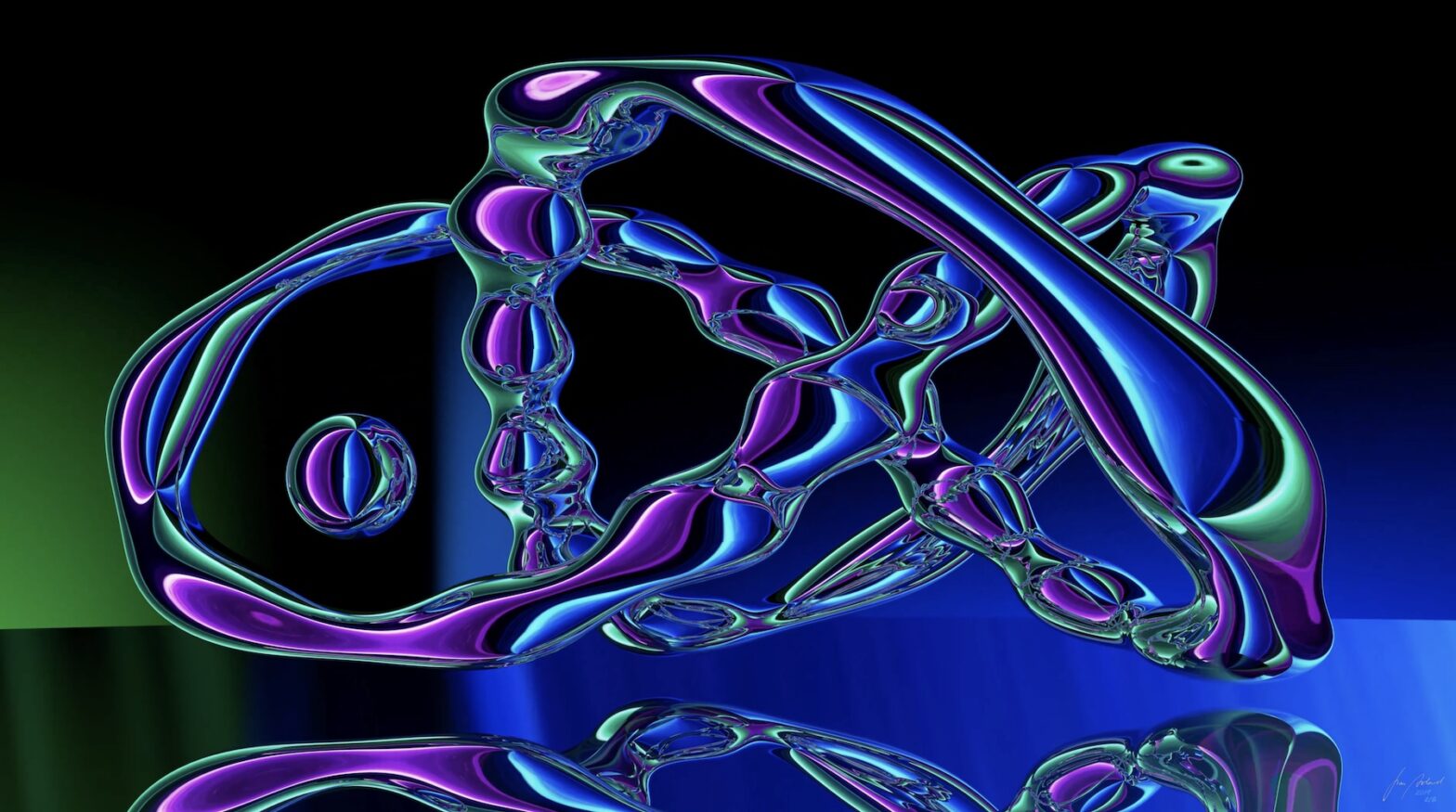

Ronen Tanchum. FEELS I, 2021

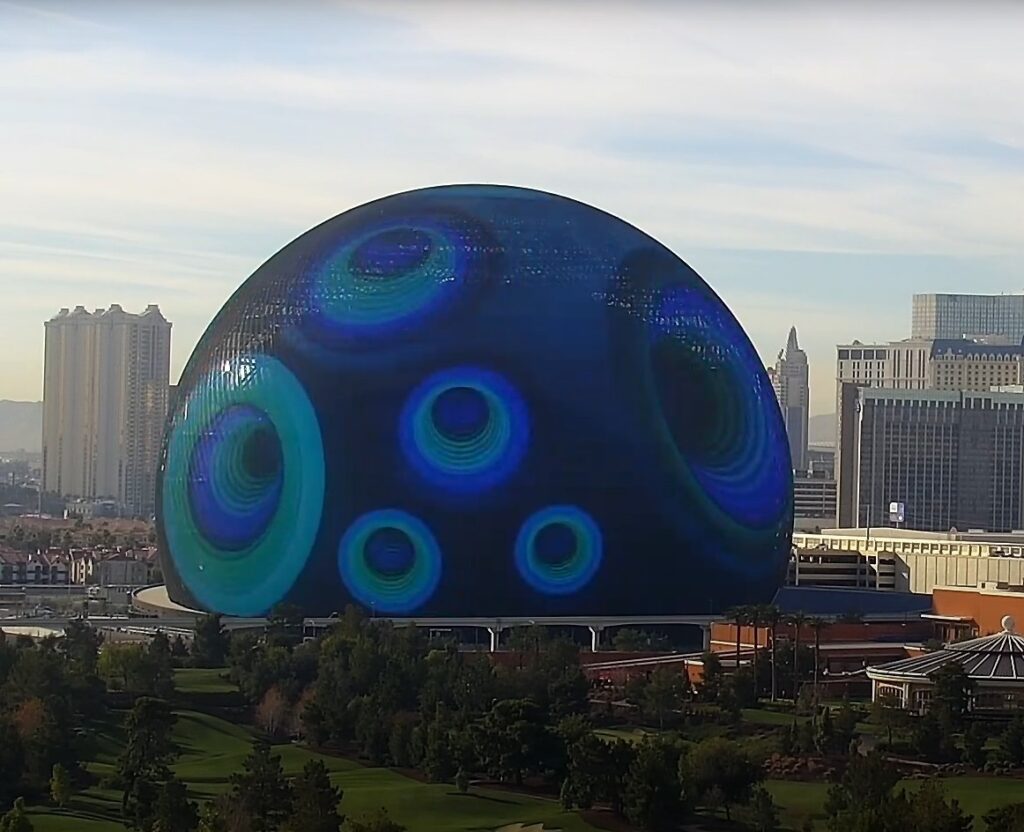

You have mentioned how the depiction of reality in films leads to spectacularity, and that is also something we frequently find nowadays in digital art, with large installations and projections in public spaces, that lead to equating digital art with a visual spectacle. As an artist, how do you see this expectation of digital art being eye-catching?

That’s an interesting question. Certainly, spectacularity is a tool to tell your story and convey or emote feelings. I do believe that art needs to be felt more than understood, and I also see that the spectacular aspect of digital art is there by choice. As a medium that is relatively new and exciting to a large audience, digital art is often perceived in this way, as something that catches your attention, and for artists that is a powerful tool to have in their hands. So, I understand the pull, both for artists and the audience, to expect spectacularity from digital art, but I also don’t feel that this is a necessity. Digital art doesn’t always have to cause a strong visual impact or be displayed in large LED screens. Of course, screens are its habitat, it is where digital art is meant to be experienced. We’re moving into a new age where art is no longer only on canvases, or sculptures, but on different mediums, and also everywhere. The screen is often understood as a digital canvas, but that is only the beginning, there will be many more ways to experience art digitally.

In my practice, I would say that it is not so much about making art that draws attention, but using the medium in interesting ways. Exploring the possibilities of software, of generative algorithms, 3D modeling, artificial neural networks and so on, to question our reality and our experience of nature is what feels interesting to me.

“Certainly, spectacularity is a tool to tell your story and convey or emote feelings. But digital art doesn’t always have to cause a strong visual impact or be displayed in large LED screens.”

Another aspect that you’ve mentioned is the idea of control. You sometimes work with software that lets you control every element, every detail and behavior. But you also work with generative algorithms and machine learning programs, with which there is more of a “dialogue.” How do you balance your creative authorship with the outputs of these autonomous systems?

A lot of my practices are procedural and generative in nature. So even when I want to create a specific thing and aim for a certain output, I test a lot of methods to get there, naturally. I’ve been building systems and algorithms before releasing them as long format and as something with the aspect of randomness in them before, and I often work with JavaScript, and GLSL, to create long format, generative art, which is not AI. It is a way to release control and let go, so it’s interesting, because at first, I start building towards something and then I find myself thinking about variations of that original intention. To give you an example: a random function gives you a different number every time and then you can use that number to perform visual modifications on the artwork. So, for instance, every time some element appears, it can have a different color or a different size or a different shape. And then I use these somewhat random functions in order to create the output. But this output that you’re looking at lives in a spectrum of outputs: every time that you iterate on the algorithm, there will be a different output. How different that new output can be, of course, depends on the degree of so-called “randomness” you give to the system. So, if I want to get a certain degree of control over this spectrum of outputs, I must limit the amount of unexpected results that might come out of it.

“Generative art on the blockchain is a match made in heaven because here the algorithm is not only producing an endless amount of random outputs, it is creating a series of artworks that people can own and say «okay, this one belongs to me.»”

I particularly like this method of working, to experience and be surprised by the interaction with the machine. Working with algorithms gives me an opportunity to do something that is not necessarily static. It could be dynamic, or it could be influenced by something and become interactive, or it could be a data sculpture, using real time data, or a data set that you train, and then play with. This is a really powerful tool: generative art and algorithmic art on the blockchain is a match made in heaven because here the algorithm is not only producing an endless amount of random outputs, it is creating a series of artworks that people can own and say “okay, this one belongs to me.” And that is really interesting because the outputs become unique, but also part of a series, and the owners of these artworks become part of a community. This generates some very interesting dynamics between the pieces of a collection and the owners of those pieces.

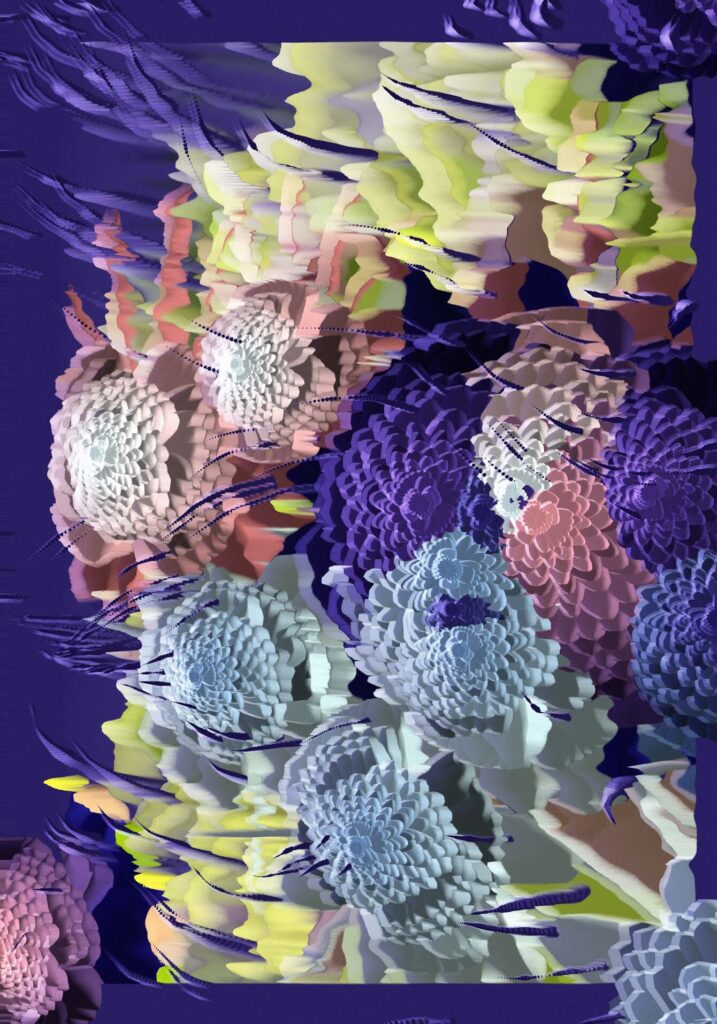

Continuing with the subject of generative art on blockchain, can you tell us about your experience with the series Rococo? How was the response to these artworks?

Rococo is a project Ori Ben-Shabat and I developed together. It is an exploration of how we can reproduce synthetically digital paintings that represent flowers. Flowers, as you know, can come in many shapes and colors, for instance with six or fifteen petals, and that gives us a lot of possibilities, in the form of functions and numbers for the algorithm. Working with the algorithm we created a type of flower that we liked, and then duplicated it a number of times, introducing variations in the number of flowers, petals, and colors. The code itself describes a bunch of spheres that move in space, and while doing so they draw and create the final painting that you see. It is a similar approach to that of a painter who would choose a brush, and a bit of paint, and then perform a series of movements spreading the paint on a canvas with the brush in order to create the image, the gestures of his hand determining the particular shape of the flowers and a certain style of depiction.

The response was very good. As you know, when you present generative art on an NFT marketplace, you put the code of the system that creates the artwork on the blockchain, then people can explore what the algorithm does prior to minting. Usually, they can explore and see the spectrum of outputs that the algorithm creates, and then they decide if they want to buy it or not. But they actually don’t know exactly which composition they will obtain, which is in a way the opposite of buying a painting. This process becomes very engaging and very surprising and personal, both to the artist and to the collector. It introduces the element of luck and chance into collecting artwork, which is an interesting way to release art. And it also creates a dynamic within the collection: some will be worth more than others, just because more people like them. This is really interesting, and it could be explored endlessly. So for instance, you can have an algorithm that creates an infinite number of outputs, but then only X amount of them are locked to the blockchain, and only those are what collectors can own.

Your work easily transitions between photorealistic 3D animations, abstract compositions, and what could be described as digital painting: artworks that explore painting as a compositional and stylistic reference using digital tools. Which of these approaches is more interesting? Which is more challenging?

What interests me is to work with the edges, to play with all of them and transition between them. I am very influenced by both traditional art and contemporary art. So in projects such as Rococo, a major goal was to find a way to use code while simulating something as materially specific and expressive as a brushstroke. This could have very well become a generator of perfectly identifiable, realistic, 3D looking flowers, but with Ori we decided that it was much more interesting to explore what the act of painting looks like and find out how to evoke the level of expression and abstraction that a painter achieves applying painting on a canvas, but using computer software.

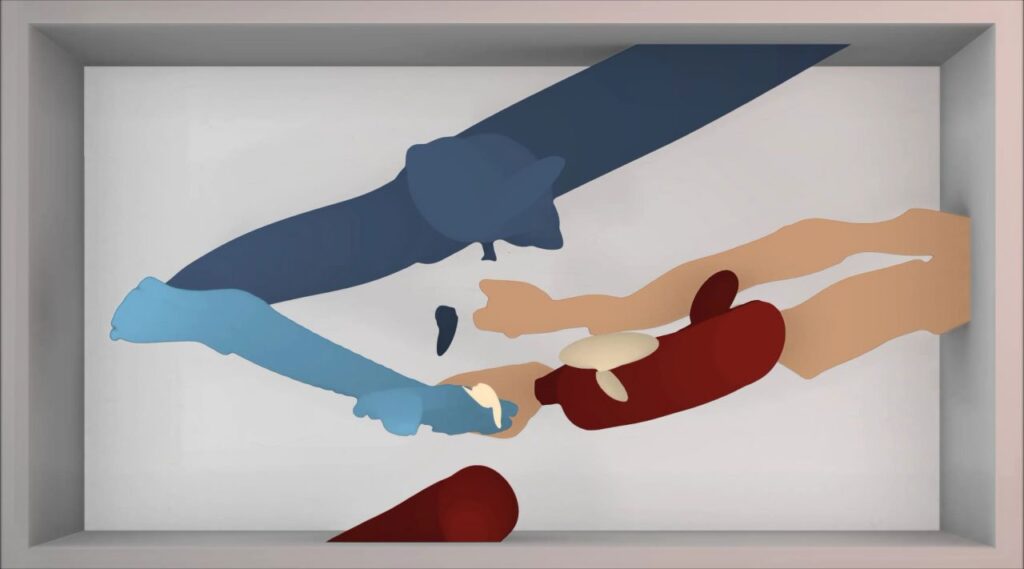

Ronen Tanchum. The Expressionists ~ Couple #2, 2020

You have mentioned your collaboration with Ori Ben-Shabat, with whom you work at Phenomena Labs, a studio that creates immersive art experiences. How does the work at Phenomena Labs differ from your individual work as an artist?

I founded Phenomena Labs almost 10 years ago with a mindset of collaborating: on the one hand, to develop a collaborative approach to creating with my friends and on the other hand, to collaborate with clients and art collectors in commissioned work. Basically, anything that I do collaboratively takes place in the context of the studio and is presented under Phenomena Labs as a brand and identity. Ori and I frequently work with other artists, designers, and architects to create immersive installations and generative art. This work is generally addressed at public spaces and large audiences.

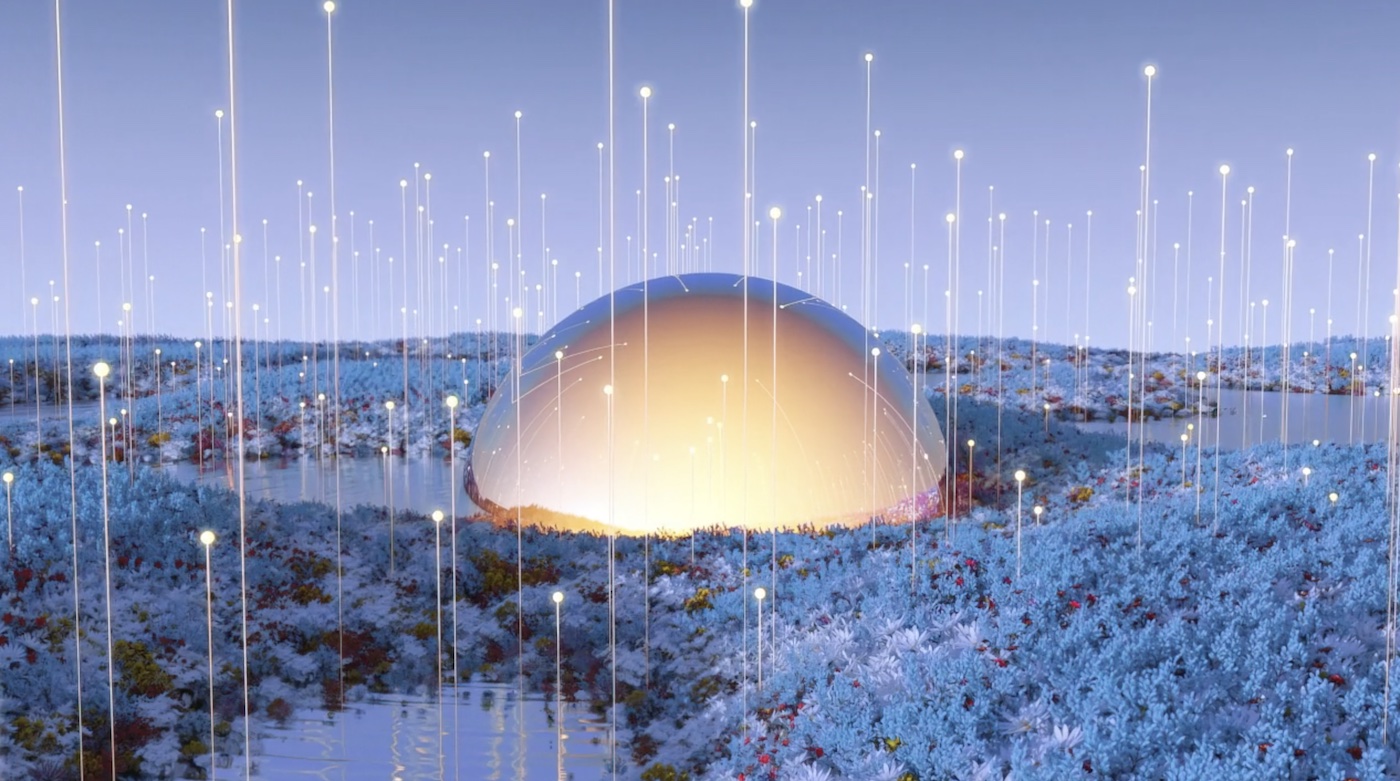

Moments in Time is a fascinating project from Phenomena Labs that connects an architectural space with its environment through real time data animations, in which we see several recurring elements in your work. Can you tell us more about this project and the possibilities of creating art with real time environmental data?

This is a unique project we’ve worked on throughout 2023. The objective was to create a mirror for the vibrant community that is about to inhabit a building in Jönköping (Sweden). We were approached by our client and the architects and we thought about a piece that is alive, and is inspiring the startup community allocated in that building. On a large screen in the lobby, the artwork displays a series of chapters, different compositions that use data in real time. We chose to use a few different metrics and data points for different visual chapters of the piece. Each data point refers to an aspect of the building and its surroundings, as well as the people inside, in order to visualize how the environment and the human activity in the building can change and evolve over time. We used motion sensing to create visual trails from the movement of people in the lobby, and turned it into a paint brush effect where people apply brush strokes on a digital canvas by walking through the lobby, thus creating a visual composition in real time. Then we used weather information to apply wind turbulence on a set of particles displayed on the screen. And we also introduced real time energy data from the building to create a virtual waterfall that becomes a sort of data visualization of all the energy that is being consumed in the building every day. It was really interesting to see that, for instance, the waterfall flows faster and has a higher volume of water when there’s people in the building, and when they go home, it settles and slows down.

You state that your work is about trying to connect humans and machines, and reflecting on our dependence on technology. Recently, the launch of Apple’s Vision Pro was greeted by enthusiastic customers who gave the world a glimpse of what is to come: more dependency on our devices, that increasingly shape how we perceive reality. As an artist and professional creator of fantastic digital realities, how do you see this relationship evolving in the future?

The launch of products like Apple’s Vision Pro remind me that in our relationship with technology, there is a constant tension between what we are familiar with and what level of innovation we are ready to adopt. This tension oscillates in cycles, so that when something pushes too much into the unknown or becomes uncertain, such as this possibility of really isolating oneself from the world, then there is a backlash. At this point, people long to go back to a simpler relationship with the environment, and instead of adding more layers of digital content to their surroundings, reconnect with nature, or at least with a calming and comforting view of nature. Finding a balance between the two and making the digital environment more familiar is a challenge that may take more than a generation.

“For me, the question is how to embrace the better aspects of digital technologies without letting them alienate us from the real world or shape our perception of the environment.”

For me, the question is how to embrace the better aspects of digital technologies without letting them –or those who market them– alienate us from the real world or shape our perception of the environment. In this sense, I intend to explore real time data in my work to let people understand and appreciate the world around them, and at the same time visualize the systems and networks that provide that data. It is important to understand that we live surrounded by systems (natural, legal, informational) that we have to think in terms of the environment and our interactions with others and with these systems. Often disruptive technologies are created thinking only in short-term solutions and specific goals that do not consider the world they will have an impact on. But there will always be a reaction from the world, society, systems, etc. Within this constant tension, and back-and-forth reactions in where gradual change, maybe progress, happens.