Pau Waelder

The following text is an excerpt from my contribution to the book The Meaning of Creativity in the Age of AI, edited by Raivo Kelomees, Varvara Guljajeva, and Oliver Laas (Tallinn: EKA, 2022). The volume is focuses on critical observations of the possibilities of Artificial Intelligence in the field of the arts and includes contributions by artists, art professionals, and scholars Varvara Guljajeva, Chris Hales, Mar Canet Solà, Jon Karvinen, Luba Elliot, Oliver Laas, Raivo Kelomees, Mauri Kaipainen, Pia Tikka, and Sabine Himmelsbach.

The book, which addresses key questions currently being debated around AI systems such as DALL-E 2 and Chat GPT, has been recently made available as a free PDF.

Can you teach your machine to draw?

On 5th February 1965, during the opening of Georg Nees’ exhibition of algorithmic art at the Technische Hochschule in Stuttgart, there was an exchange between the engineer and an artist who asked him provocatively if he could teach the computer to draw the same way he did. Nees replied that, given a precise description, he could effectively write a program that would produce drawings in the artist’s style (Nake, 2010, p.40). His response echoes the conjecture that had given birth to the field of artificial intelligence ten years earlier: that “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it” (Moor, 2006, p.87). It should be noted that, at least at this point, the machine is not meant to think or create, but simulate. In his seminal paper from 1950, Alan Turing already suggested that computers could perform an “imitation game” (later known as the Turing Test) in which the aim was to mimic human intelligence to the point of seeming human to an external observer (Turing, 1950).

Therefore, what Nees asserted is that the computer could create a successful imitation of the artist’s work. The exchange between Nees and the artist did not go well, as the engineer’s vision of a computable art seemed to threaten the superiority of artistic creativity. Upset and resentful, the artist and his colleagues left the room, with philosopher Max Bense trying to appease them by calling the art made with computers “artificial” (Nake, 2010, p.40) – as opposed, one might think, to a “natural” art made by human artists. The need for this distinction denotes the uneasy relationship between artists and their tools, the latter supposedly having no agency at all, being mere instruments in the skilled hands of the artist.

The computer introduced an unprecedented level of autonomy: the artist only needed to write a set of instructions, the program did the rest.

Certainly, there had been some room for randomness and uncontrolled processes to emerge in the different artistic practices that had succeeded each other during the 20th century, but until that point creativity was unquestionably anthropocentric, with the artist (or their assistants), at the centre of the creation of every artwork. The computer introduced an unprecedented level of autonomy: the artist only needed to write a set of instructions, the program did the rest. This was challenging for artists at a time when few had seen a computer and even fewer knew how to write a program or understood what it could do.

Despite the profound differences from our current perception of computers, over fifty years later, AI still holds the same fascination and is subject to the same misunderstandings as early computer art. The initial rejection of computer-generated art has turned to uncritical enthusiasm, and the prospect of an art that does not need human artists has been celebrated with a spectacular sale at Christie’s. But the artist was never out of the picture.

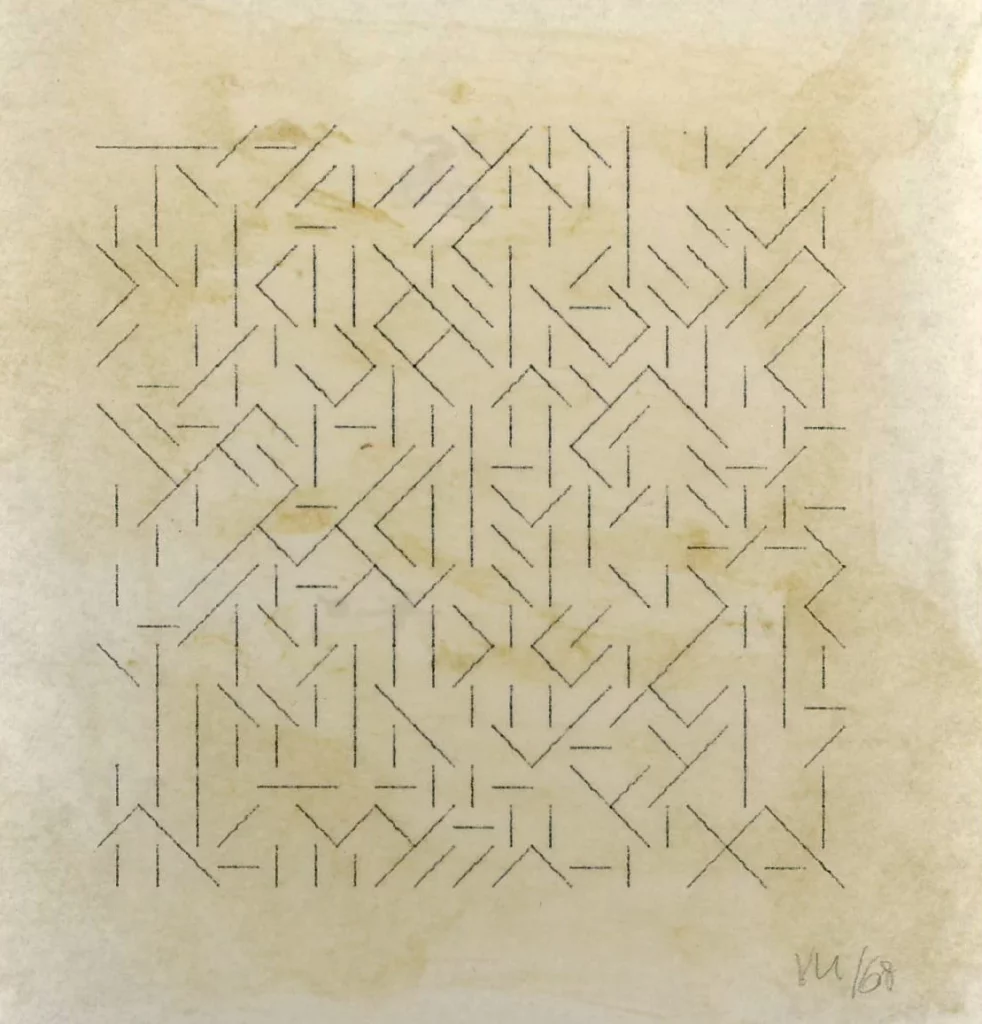

Pioneering computer artist Vera Molnar created her first artworks in the 1960s with a “machine imaginaire”, a program for an imaginary computer that helped her develop a series of combinatorial compositions of geometric forms and colours. In 1968, she started working with a real computer (which back then was only available at a research lab), but she has always stressed that the machine is, to her, nothing but a tool: “The computer helps, but it does not ′do′, does not ′design′ or ′invent′ anything” (Molnar, 1990, p.16).

“The computer helps, but it does not ′do′, does not ′design′ or ′invent′ anything”

Vera Molnar

Another pioneer, Frieder Nake, recalls the experience of creating his first algorithmic drawing in 1965, underscoring his role as the creator of the artwork:

“Clearly: I was the artist! A laughable artist, to be sure. […] But an artist insofar as he – like all other artists – decided when an image was finished or whether it was finished at all and not rather to be thrown away. I developed the general software, wrote the specific program, set the parameters for running the program. […] I influenced the process of materialization by choosing the paper, the pens, and the inks; and I finally selected the pieces that were to be destroyed or to leave the studio to be presented to the public.”

Nake, 2020

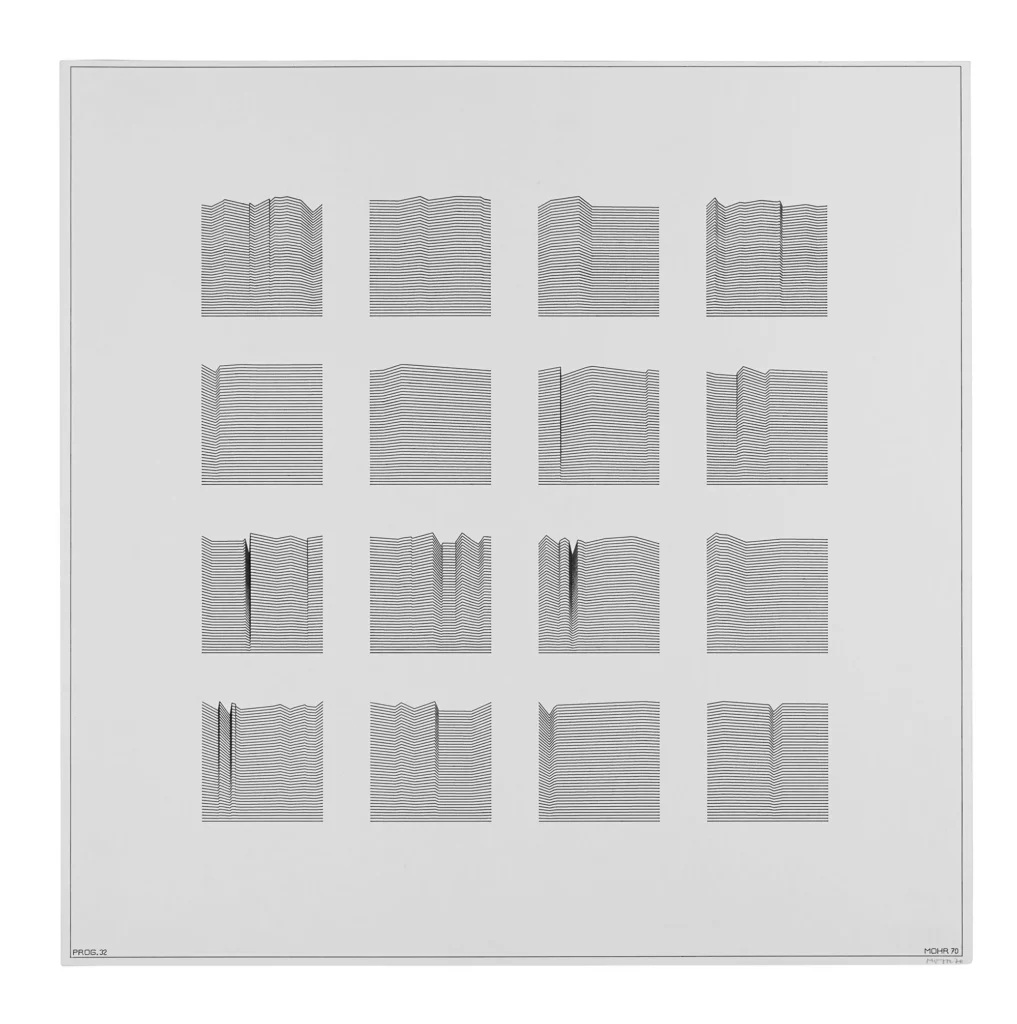

Manfred Mohr, one of the first artists to work with computers who, like Molnar, had a background in fine arts instead of mathematics, has frequently stated that his artworks transcend the computational process they are based on: “My artistic goal is reached” he states, “when a finished work can visually dissociate itself from its logical content and convincingly stand as an independent abstract entity” (Mohr, 2002).

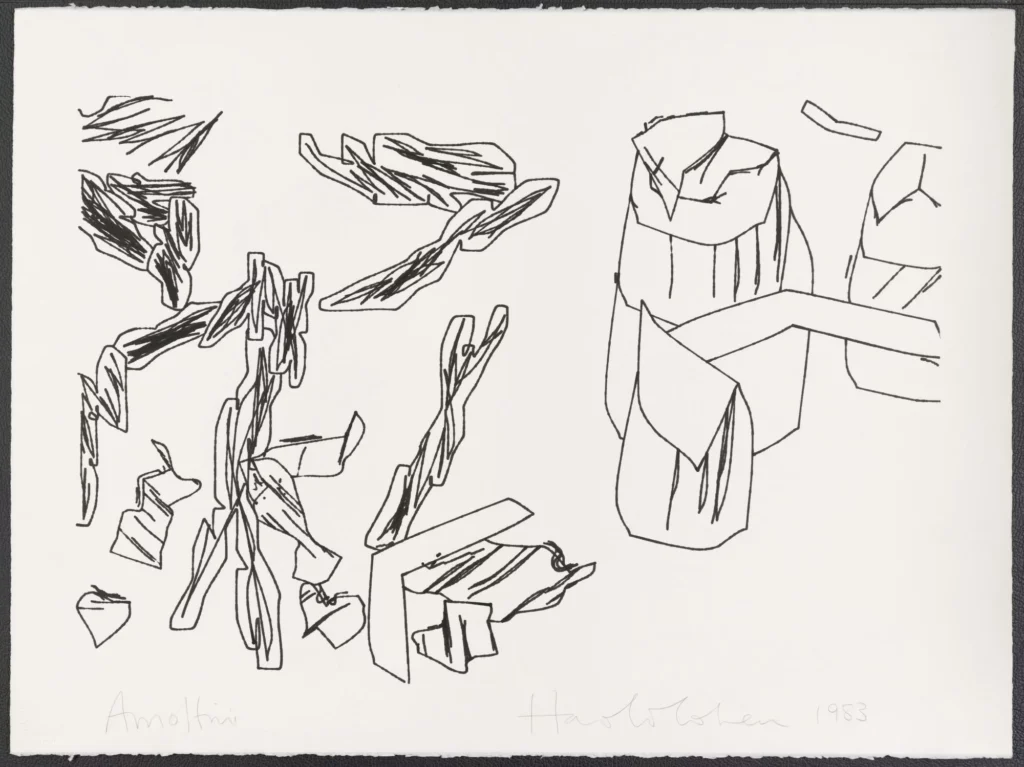

Algorithmic artists have played with the balance between control and randomness, always keeping a direct involvement in every part of the process of creation, from the code to the final output. The software, however, can be allowed a greater portion of the decision making. This is what Harold Cohen did in 1973 when he developed AARON, a computer program designed to generate drawings on its own, with no visual input, based on a complex series of instructions written by the artist.

Influenced by the ideas that were being discussed at Stanford University’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at the time, Cohen sought to understand how images were made. AARON aimed to answer that question by creating drawings that simulated those of a human artist, without human intervention. Cohen stressed AARON was “not an artists’ tool” but “a complete and functionally independent entity, capable of generating autonomously an endless succession of different drawings” (Cohen, 1979). This autonomy led to thinking about AARON in cognitive terms, with Cohen himself stating that the program “has a very clear idea of what it is doing” (Cohen and Cohen, 1995, p.3). For over four decades, the artist kept developing the program, establishing a relationship that he described as the kind of collaboration one would have with another human being:

“AARON is teaching me things all the way down the line. From the beginning, it has always been very much a two-way interaction. I have learned things about what I want from AARON that I could never have learned without AARON”

Cohen and Cohen, 1995, p.12

Cohen’s work prefigured the current applications of AI systems in art making, not only in the way the program worked but also in its role as a collaborator rather than a mere tool.

Artists working with artificial neural networks nowadays describe their experience in similar terms to those expressed by AARON’s creator. When Anna Ridler created her own dataset of 200 drawings to train a GAN for her animated film Fall of the House of Usher I (2017), she sought to push the boundaries of creativity by producing an artwork that is a machine generated interpretation of her drawings, which in turn represent scenes from a silent film based on a short story by Edgar Allan Poe. The outcome has led her to wonder where is the “real” artwork, and to doubt the role that the program plays in its making: “I do not see a GAN as a tool like I would think of say a photoshop filter but neither would I see it is as true creative partner. I’m not really quite sure what is is” (Ridler, 2018).

For Patrick Tresset, working with robots that can draw in their own style enables him to distance himself from his work: “I found it very difficult to show my work, as a painter, as an emotional thing, and the distance that we have with the action when you use computers, that you are not directly involved… makes it far easier for me to exhibit” (Upton, 2018).

Memo Akten explores the structure and functioning of artificial neural networks and uses Machine Learning as a form of exploring human thinking: “My main interest,” he states, “is in using machines that learn as a reflection on ourselves, and how we navigate our world, how we learn and ‘understand’, and ultimately how we make decisions and take actions” (Akten, 2018).

Gregory Chatonsky criticizes the perception of the artist as purely autonomous and the machine as a simple tool, while describing his creative process as an interaction with the software that not only generates images but also spurs his imagination: “Working with a neural network to produce images or texts,” he states, “I perceive how my imagination develops, becomes disproportionate and germinates in all directions. I try to adapt to this rhythm, to this breath. It’s almost alive” (Chatonsky, 2020).

Artists have carried out a dialogical relationship with the software they have used, considering it not just an instrument, but a collaborator.

These statements show that artists have carried out a dialogical relationship with the software they have used, considering it not just an instrument, but a collaborator. However, the deeply entrenched perception of the artist as the sole creator of the artwork, in full control of every aspect of the outcome, looms over this partnership insisting that either the machine is to remain a mere tool or it is destined to take over the artist’s role.

Towards post-anthropocentric creativity

The question whether a machine can be creative is recurrently asked as AI systems increase their capabilities and become more sophisticated. Recently developed systems such as CAN (Creative Adversarial Network), which is taught to deviate from the examples it has learnt in order to produce new types of images (Elgammal et. al., 2017), or DALL-E, which can generate images from text descriptions (Ramesh et. al., 2021), illustrate how far computers can go in creating visual content.

CAN has even been used in an attempt to pass the Turing Test, that is, to produce machine-generated art that appears indistinguishable from that created by an artist. The results have been disputed in a study that shows a preference for art made by humans and suggests that what should be asked is not if AI can create art, but whether the art created by AI is worthy (Hong and Ming, 2019).

What should be asked is not if AI can create art, but whether the art created by AI is worthy.

Seen from this perspective, the debate pivots to more practical considerations: what can AI do, and how can it be used? GANs are widely employed by artists nowadays, but they tend to generate the same type of images because of the limitations of the programs and the processors. In this sense, the artificial neural networks are not particularly creative because they do not produce anything that breaks out from a set of established parameters and similar outputs. The creativity stems from how artists use these images and assign them a certain narrative. Therefore, to expect machines to become creative by following problem-solving approaches seems limiting and even counterproductive (Esling and Devis, 2020), given that we don’t even understand how creativity works and cannot translate it into computable formulas.

Instead of asking whether an AI system can replace an artist, it would be more interesting to consider how artists can expand their creativity using AI. This proposition does not imply considering the artist as the sole creator of the artwork, but moves past this preconception to embrace a notion of creativity that includes all the actors involved, human and non-human.

Jan Løhmann Stephensen suggests the terms “postcreativity” or “postanthropocentric creativity” to challenge the idea of creativity as something that is exclusive to humans and a marker of human “greatness” (Løhmann, 2019). Through the lens of postcreativity, we can consider artworks as the outcome of an interaction between a variety of actors, including humans, objects, systems, and environments. In AI-generated art, this means taking into account all the people, animals, natural environments, institutions, communities, software, networks, etc. that take part, more or less directly, more or less willingly, in the artwork’s making.

This opens up deeper reflection on how the piece is created, as do Anna Ridler and Memo Akten in their examination of the artificial neural networks they use. It also allows artists to distance themselves from the specific output while retaining authorship of the process, as do Patrick Tresset and Guido Segni – the latter currently engaged in a five year project titled Demand Full Laziness (2018-2023), in which he outsources his artistic production to a deep learning algorithm trained with images from his moments of rest. Overall, it emphasises the potential of co-creation between humans and machines, in which computers do not mimic, but expand human creativity.

Through the lens of postcreativity, we can consider artworks as the outcome of an interaction between a variety of actors, including humans, objects, systems, and environments.

Artificial Intelligence has developed at a growing pace over the past seven decades, and it will continue to do so, bringing new challenges and possibilities for computer-generated art. As several authors point out, AI is currently at a stage equivalent to the daguerrotype in photography (Aguera, 2016; Hertzman, 2018), and it is difficult to predict what novel forms of creativity it will unfold. It might well be, if AI were to reach a stage of consciousness or self-volition, that a program may not be interested in producing a drawing or a photograph and would rather express itself through elegant programming code or a beautiful mathematical equation. Or, maybe it would even create art that is not intended for humans to understand, but is addressed to fellow AIs.

This text was written in March, 2021

References

Aguera, B., 2016. Art in the Age of Machine Intelligence. Medium, [online].Available at: https://medium.com/artists-and-machine-intelligence/what-is-ami-ccd936394a83 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Cetinic, E., and She, J., 2021. Understanding And Creating Art With Ai: Review And Outlook. Cornell University [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.09109 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Chatonsky, G., 2020. Imaginer avec le possible des réseaux de neurones. Gregory Chatonsky, [online]. Available at: http://chatonsky.net/imager-neurones/ [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Cohen, B. and Cohen, H., 1995. Conversation: Harold Cohen & Becky Cohen. In: The Robotic Artist: Aaron in Living Color Harold Cohen at The Computer Museum. Boston: The Computer Museum. Available at: https://dam.org/museum/essays_ui/essays/the-robotic-artist/ [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Cohen, H., 1979. What is an image?. AARON’s home, [online]. Available at: http://www.aaronshome.com/aaron/publications/index.html [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Cohn, G., 2018. AI Art at Christie’s Sells for $432,500. The New York Times, [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/25/arts/design/ai-art-sold-christies.html [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Elgammal, A., Liu, B., Elhoseiny, M., Mazzone, M., 2017. CAN: Creative Adversarial Networks Generating “Art” by Learning About Styles and Deviating from Style Norms. Cornell University [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.07068 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Esling, P., and Devis, N., 2020. Creativity In The Era Of Artificial Intelligence. Cornell University [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2008.05959v1 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Hertzmann, A., 2018. Can Computers Create Art?. Arts, 7(2), 18. [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7020018 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Hong, J. and Ming Curran, N., 2019. Artificial Intelligence, Artists, and Art: Attitudes Toward Artwork Produced By Humans vs. Artificial Intelligence. ACM Trans. Multimedia Comput. Commun. Appl., 15(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3326337 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Løhmann Stephensen, J., 2019. Towards a Philosophy of Post-creative Practices? – Reading Obvious’ “Portrait of Edmond de Belamy.” In: Politics of the Machine Beirut 2019 (POM2019). [online] Beirut: BCS Learning and Development Ltd., pp.21-30. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/POM19.4 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Marcus, G. and Davis, E., 2019. Rebooting AI. Building Artificial Intelligence We Can Trust. New York: Pantheon Books.

Mohr, M., 2002. Artist’s Statement. Ylem Journal, Artists using Science & Technology, 22(10), p.5.

Molnar, V., 1990. Lignes, Formes, Couleurs. Budapest: Vasarely Múzeum.

Moor, J., 2006. The Dartmouth College Artificial Intelligence Conference: The Next Fifty Years. AI Magazine, 27(4), pp.87-91.

Nake, F., 2010. Roots and randomness –a perspective on the beginnings of digital art. In: W. Lieser, ed., The World of Digital Art. Postdam: h.f. Ullmann, pp.39-41.

–– 2020. Three Drawings and one Story. DAM Museum, [online]. Available at: https://dam.org/museum/essays_ui/essays/three-drawings-and-one-story/ [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Ramesh, A., Pavlov, M., Goh, G., Gray, S., Voss, C., Radford, A., Chen, M., Sutskever, I., 2021. Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation. Cornell University [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.12092 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Ridler, A., 2018. Fall of the House of Usher. Datasets and Decay. The Victoria and Albert Museum, [online]. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/museum-life/guest-blog-post-fall-of-the-house-of-usher-datasets-and-decay [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Russell, S. and Norvig, P., 2010. Artificial Intelligence. A Modern Approach. Third edition. Boston: Prentice Hall.

Turing, A.M., 1950. Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind, LIX(236), pp.433–460. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Upton, D., 2018. Interview with Patrick Tresset by David Upton for the Computer Arts Society. YouTube, [online]. Available at: https://youtu.be/vb1Cj0fVq1M [Accessed 14 March 2021].