Pau Waelder

Centre d’Art Lo Pati in Amposta opens a new season of screenings in the art center’s building façade. Following an art program curated by Irma Vilà, I have been invited by the director of Lo Pati, Aida Boix, to curate a new selection of artworks for 2024. Titled Anthroposcenes: narratives about life in the Anthropocene, it features the work of Diane Drubay, Claudia Larcher, Kelly Richardson, Theresa Schubert, Yuge Zhou, and Marina Zurkow. In the following text, I introduce the concept behind this curatorial project and the work of the artists.

The term “Anthropocene” was proposed in 2000 by the ecologist Eugene Stoermer and the Nobel laureate in chemistry Paul Crutzen to indicate the decisive influence of human activity on our planet. It carries the danger of accepting that our actions are irreparable, but at the same time it gives us a sense of responsibility in our relationship with the environment. Understanding the consequences of our consumption habits and our daily activities in an ecosystem pushed to the limit by the abuse of natural resources, the production of waste and pollution is both a necessity and a duty.

The notion of the Anthropocene can lead us to think that the effects of human activity on the planet are just a consequence of the evolution of our species.

Philosopher and biologist Donna Haraway indicates that the danger of talking about the Anthropocene is that it leads us to consider that the effects of human activity on the planet are inevitable, and that this is just a consequence of the evolution of our species. For this reason, she proposes the term “Capitalocene,” pointing out that it is the capitalist exploitation of the Earth’s resources, including human beings, that leads to the destruction of the environment. The philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour also indicates that it is practically impossible to study a phenomenon such as the Anthropocene from a purely scientific, distant and objective perspective, because we find ourselves embedded in the very phenomena we are trying to study .

We therefore find that the notion of the Anthropocene is both very obvious but also in a certain way invisible, as it points to something as commonplace as our daily activity. As humans, we need to exploit natural resources to obtain food, warmth, and shelter, but we also extract resources to fulfill the numerous needs created by a consumer society taken to the greatest excesses by the very functioning of a globalized capitalist system. The Anthropocene is often linked to climate change and the danger of mass extinction, but even if we manage to avoid a planetary disaster, our way of life leads us to create an environment in which it will be increasingly difficult to live.

In this aspect, we must also remember, as the geographer Erle C. Ellis points out, that there are “better and worse lower case «anthropocenes»” depending on how the changes that occur in the environment affect us. In the most industrialized countries, we still do not suffer many effects from the extraction of minerals, the massive use of plastics, the production of waste from the fashion or technology industries, among others, because we divert them to poor countries. That is why it is essential to understand this phenomenon as something in which we participate daily, and to become aware of it we not only need a big poster telling us to recycle more and consume less, but also a narrative, or a series of narratives that make us think about life in the Anthropocene and can lead us to adopt a different mentality, born of conviction and not of guilt or a regulation.

We need narratives that make us think about life in the Anthropocene and can lead us to adopt a different mentality, born of conviction and not of guilt or a regulation.

The facade of Centre d’Art Lo Pati incorporates a screen that brings art to the street and is therefore an ideal space to show these narratives: six audiovisual works created by artists from the international scene that offer us, from different perspectives, narratives about life in the Anthropocene, particularly in those environments and systems that we ignore but that play a determining role in life on Earth. From the ocean floor to the mines from which we extract the materials that facilitate our digital life, from glaciers to atmospheric phenomena, from forest fires to crowded cities, these works invite us to reflect on our planet, the world in which we want to live and what we will leave to the next generations.

Marina Zurkow. OOzy #3: Just because you can’t swim in it doesn’t mean it isn’t there, 2022.

The ocean, a “capitalist Pangea”

The artist Marina Zurkow (New York, USA, 1962) opens this cycle with a work that takes us to the bottom of the ocean. A good part of her work focuses on this natural environment of which she points out that it is “a surface and a volume. The surface, which is what we humans mainly experience, is a space in which we play and a surface through which we transport goods, this is what turns the ocean into a capitalist Pangea.” Zurkow points out that, while we look to the sea or the ocean as a space in which to relax and dream, we use it as a dumping ground and exploit its resources without considering its sustainability. In the artwork OOzy #3: Just because you can’t swim in it doesn’t mean it isn’t there (2022), she imagines life 6,000 meters under the sea, in an environment where humans could not live. She represents this underwater landscape in vivid colors, in a playful way, because she believes that it is through humor and apparent innocence that a message can be communicated in a way that is not paternalistic or authoritarian. The work invites us to enjoy a fanciful vision that can entertain us, but over time it will also lead us to think about how the elements that appear in it (underwater probes and other devices created by humans) are alien and invasive.

Claudia Larcher. Noise above our heads, 2016.

What lies beneath the iceberg

Zurkow refers to the “iceberg model” proposed by researcher Donella Meadows to point out that we often focus on the effects (the visible part of the iceberg) and not on the structures, systems and mental models that lead to these effects, and which are usually hidden or ignored. In Noise above our heads (2016) the artist Claudia Larcher (Bregenz, Austria, 1979) takes us deep into the earth’s surface to explore a different landscape, the crust of rock that supports the weight of humanity and provides the resources that have shaped our consumer society, dependent on fossil fuels and dominated by information technologies. Deeply interested in the way in which architecture conditions our environment, Larcher introduces between the rocks fragments of architectural constructions, masses of cement that refer to the physical infrastructure of cities, and also data processing centers, hidden in cavernous spaces. “As for architecture,” says the artist, “I am drawn to its power to create, change and destroy our environment.”

The Earth’s crust supports the weight of humanity and provides the resources that have shaped our consumer society, dependent on fossil fuels and dominated by information technologies.

Diane Drubay. Ignis II, 2021.

Stories of possible futures

While Larcher’s video takes us underground, the work of artist Diane Drubay (Paris, France) invites us to look up to the sky. We see a captivating landscape with brightly colored clouds, which slowly turn reddish and increasingly dark. Ignis II (2021) is an animation of only 14 seconds, representing the fourteen years that, in 2021, remained until the so-called “point of no return” in climate change: the year 2035. According to the most recent reports, already in 2029 it will be impossible to limit the global rise in temperatures to 1.5 degrees. Instead of showing a countdown or a graph with an upward curve, Drubay creates an alluring, almost abstract landscape that tells a story solely by transforming the colors in the image. The effect is hypnotic, and if we think about what it represents, quite terrifying. The artist emphasizes the cyclical nature of the work and its leisurely rhythm: “my art requires slowness, but above all, sustainability. The notion of time and cycle is present in my work to position it in an infinite space of time that can be easily assimilated to that of nature.” Drubay’s piece, under its ephemeral beauty, leads us to reflect on slow but inexorable processes, and our ability to react to them.

Kelly Richardson. HALO I, 2021.

Memories of a lost past

In the work HALO I (2021), the artist Kelly Richardson (Ontario, Canada, 1972) takes up the theme of Camp, a video filmed in 1998. The vision of the moon during a summer night under a campfire evokes in the artist fond memories of childhood and adolescence. In this work, it acquires a new meaning as we see our satellite subjected to increasing heat. Today, bonfires have been banned in British Columbia (where the artist lives) due to the risk of forest fires. Richardson consciously evokes a scene that has emotional connotations (the tranquility of a summer night, leisure time with friends and family) and adds to it a situation of imminent danger. She wants to establish a connection that leads the viewer to react. “Beauty invites viewers to pay attention to a subject that may be difficult for them. The tragedy lies in showing the truth about what we have created, the conditions we find ourselves in, and the call we collectively face.” Unlike Drubay, who presents us with a possible future, Richardson evokes a lost past to incite us to reflection and action.

“Beauty invites viewers to pay attention to a subject that may be difficult for them. The tragedy lies in showing the truth about what we have created”

Yuge Zhou. Interlinked II, 2022

Sisyphus routines

Paradoxically, our society is very active, but it is mostly immersed in an incessant activity marked by capitalist production and consumption systems. This is made obvious in the artwork Interlinked II (2022) by Yuge Zhou (Beijing, China, 1985), an artist who resides in Chicago and in her work often observes interpersonal dynamics in American society. Zhou works with video collage to break the singularity of the moving image and tell multiple stories at the same time, turning a scene into a narrative space rich in different scenes. These scenes are often protagonized by people going about their daily or recreational activities. In this piece we see a multiplicity of sequences filmed in the New York subway in which travelers walk along platforms and corridors without a specific destination. The composition leads to thinking about what the artist calls “Sisyphus routines,” which ultimately lead nowhere and expose the absurdity of everyday life in big cities. Referring to the flâneur, or the flâneuse in this case, Zhou describes how she stands outside the flow of activity she wants to portray, indicating that this is the way to observe and reflect on what we take for granted and consider permanent.

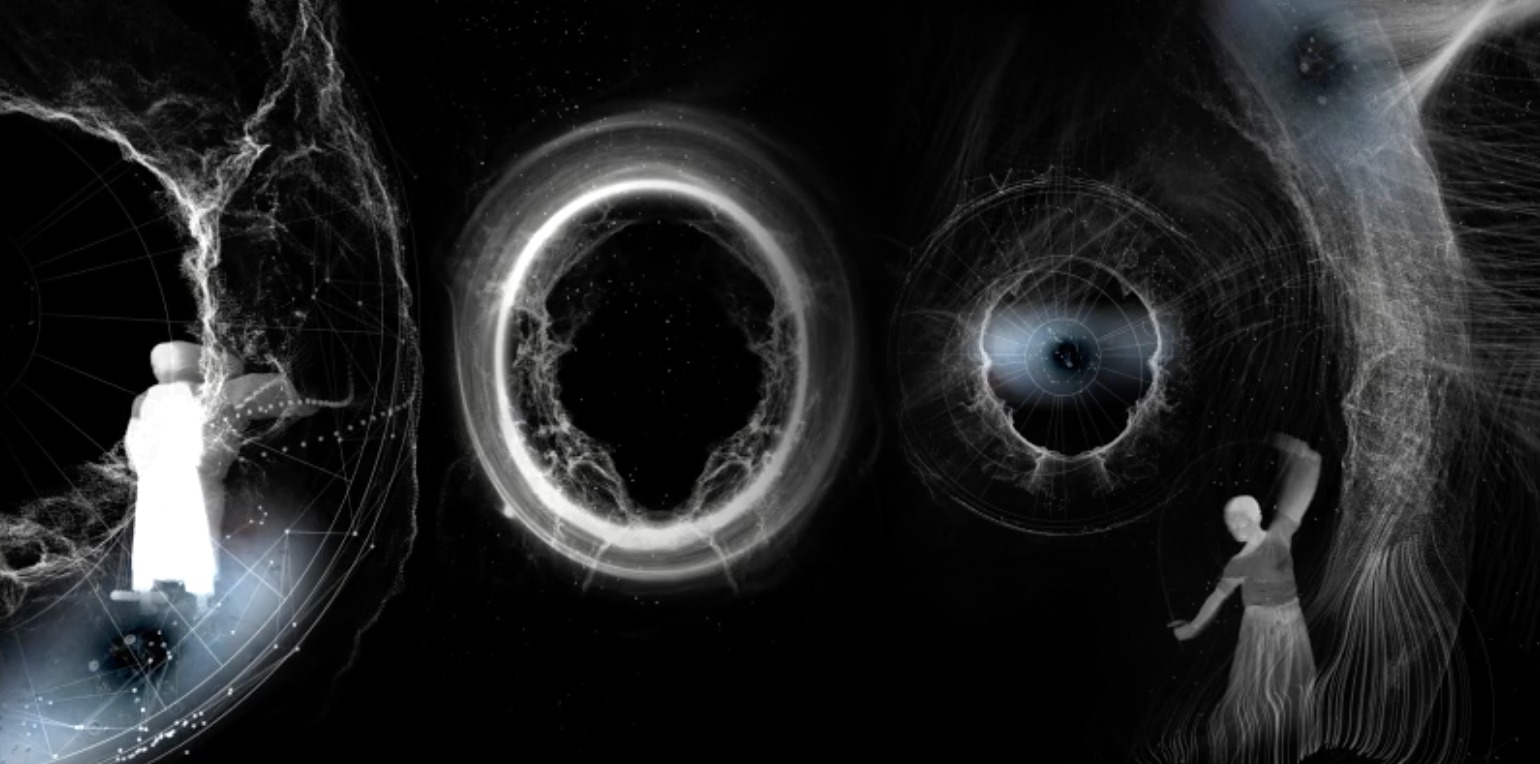

Theresa Schubert. A synthetic archive (AI glaciers), 2023.

Nothing is permanent

The last work in the series, created by the artist Theresa Schubert (Berlin, Germany, 1983) using artificial intelligence systems, explores the gradual disappearance of glaciers, a powerful image of climate change that reminds us that nothing is permanent. A synthetic archive (AI glaciers) (2023) creates a visual poem using images generated by machine learning algorithms and a sound composition that combines music, choral singing, and the voices of various narrators. The artist studied the fluvial systems in the Piemont region in Italy and collected data that was then fed to three generative adversarial networks. The fluid way in which the mountain landscapes generated by these computer programs are transformed speaks to us of a nature that, far from being static, is subject to constant transformations, which are now accelerating due to human action. Artificial intelligence, a profoundly human creation that also brings with it a particular threat of extinction, is the most appropriate tool to visualize the idea that the world is slipping under our feet.