Pau Waelder

This interview is part of a series dedicated to the artists whose works have been selected at the SMTH + Niio Open Call for Art Students. The jury been selected at the SMTH + Niio Open Call for Art Students. The jury members Valentina Peri, curator, Wolf Lieser, founder of DAM Projects/ DAM Museum, and Solimán López, new media artist, chose 5 artworks that are being displayed on more than 60 screens in public spaces, courtesy of Led&Go.

Bruno Tripodi is a 26-year-old Chilean audiovisual artist whose work merges cinema with new technologies. Raised in a creative family, his early exposure to film sets inspired him to study audiovisuals. In 2020, he began experimenting with TouchDesigner, leading to work as a Video Jockey and co-founding Sonda Tecnopoética, exploring sound synthesis and digital art. By 2022, he was creating music videos, commercials, and documentaries for a production company. Bruno aims to fuse cinema and new media, encouraging deeper appreciation and new perspectives on these artistic forms.

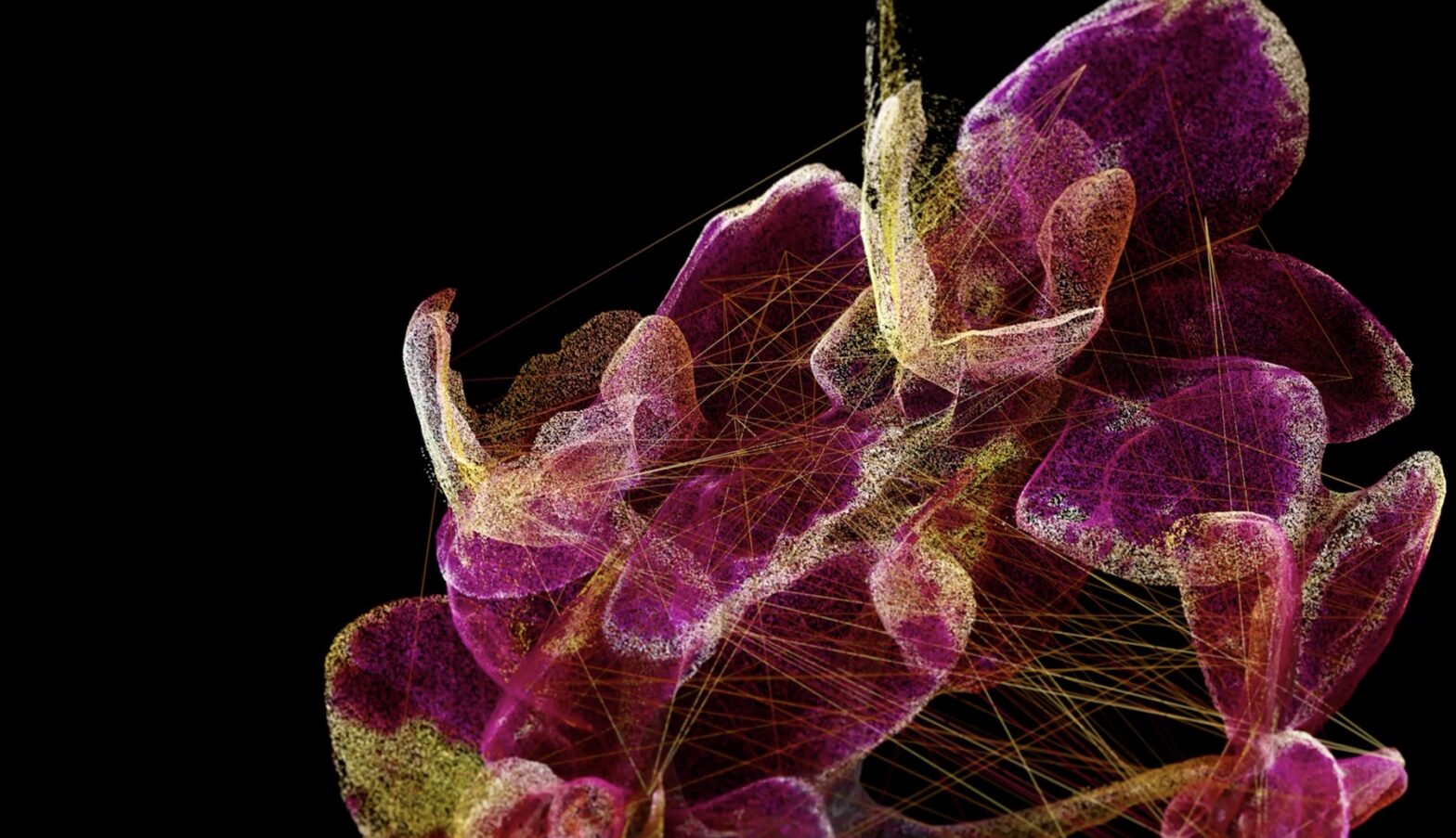

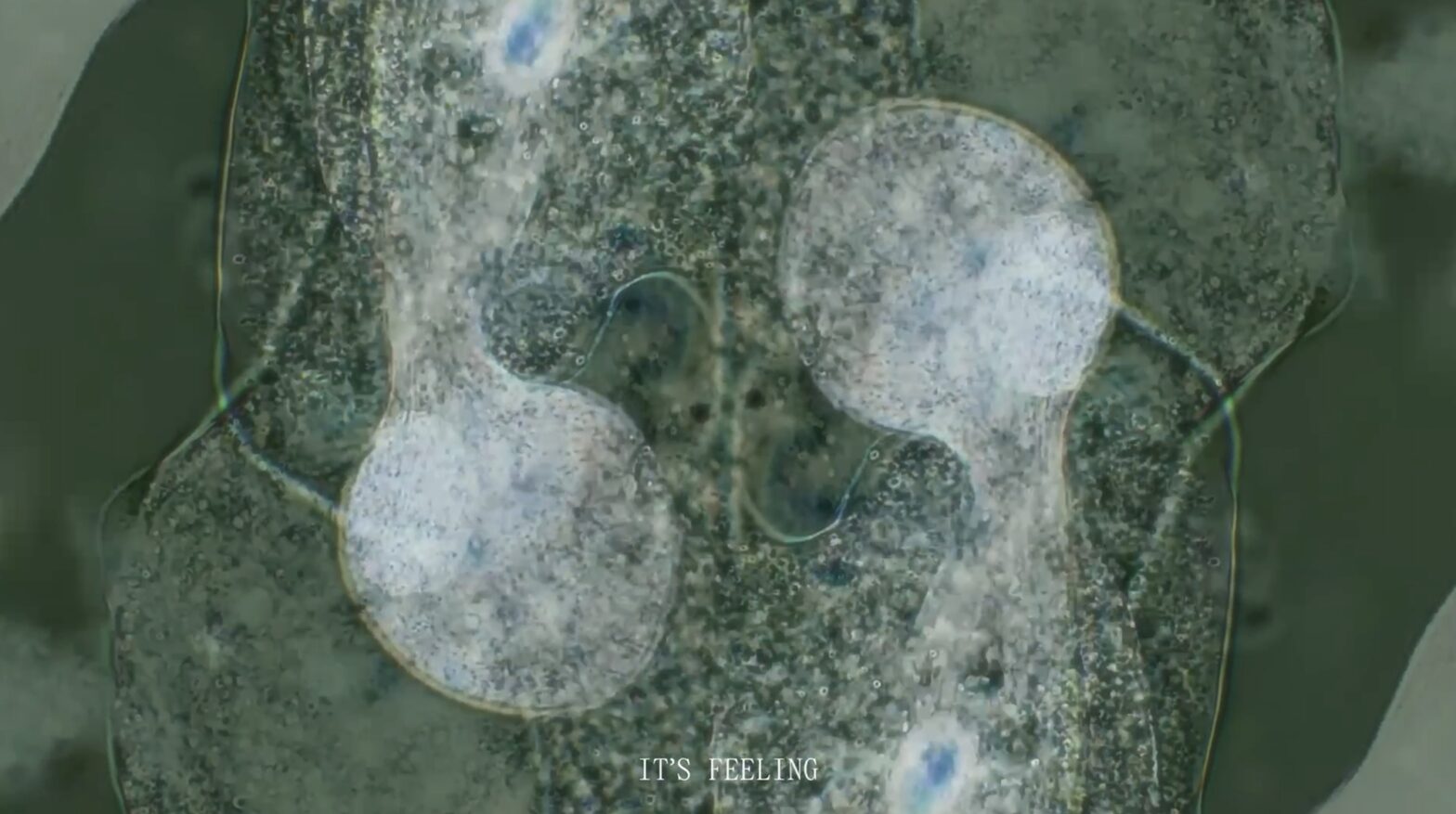

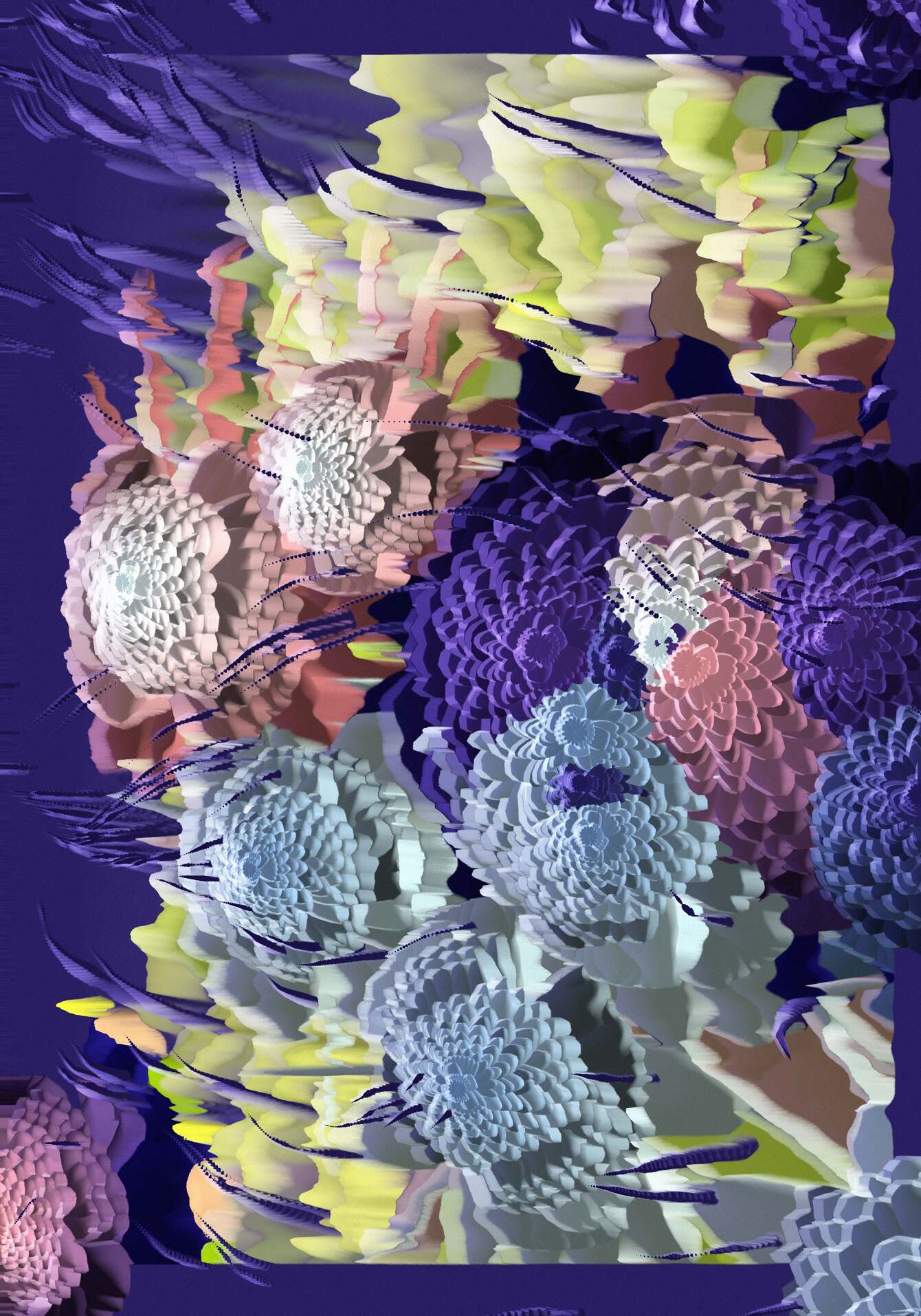

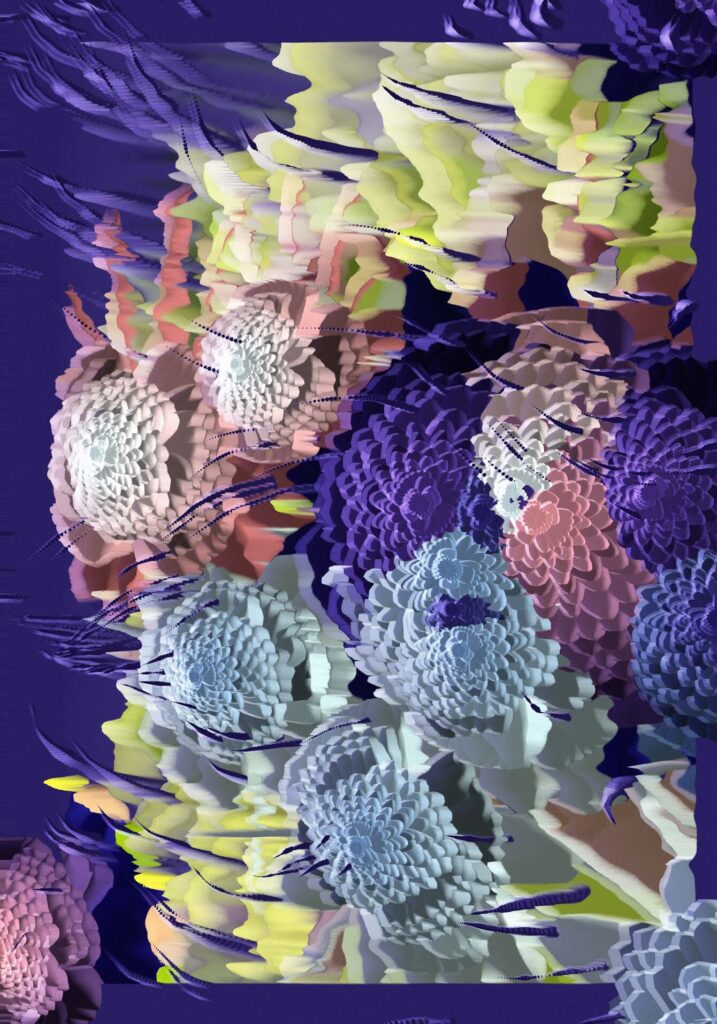

Bruno Tripodi. Desvanecer, 2024

Your work combines an interest in visual art made with digital media and sound art. What attracts you to these disciplines, and how do you combine them in your work?

From an early age, my best friend and I immersed ourselves in electronic music, exploring its many facets and participating in communities where we shared a passion for DJing and live performances. Together we would travel to festivals in other countries to see performances by DJs who did not visit Chile due to the scarce electronic music culture in the country.

During one of those trips, in Colombia, I was fascinated by the visuals displayed on a giant screen. This experience transformed me. At that moment I knew I wanted to get involved in that world. That’s how I started exploring new media and experimenting with tools like TouchDesigner. My approach has always been to combine animations with music, looking for a harmonious integration between both elements to create meaningful works.

As time went by I also started to define myself as a visual artist. My initial inspiration came from music, but I gradually evolved towards creating animations that complement the music I love. In my work Desvanecer, for example, I not only incorporate visual elements, but I also create the sound. I use the image data and turn it into channels to generate sounds, allowing the images (flowers) to produce their own sound as an allusion to the fact that they are expressing themselves.

You are co-founder of the project Sonda Tecnopoética, can you tell us a little more about this group, its members and its trajectory? How would you compare the dynamics of collective work and individual work as a creator?

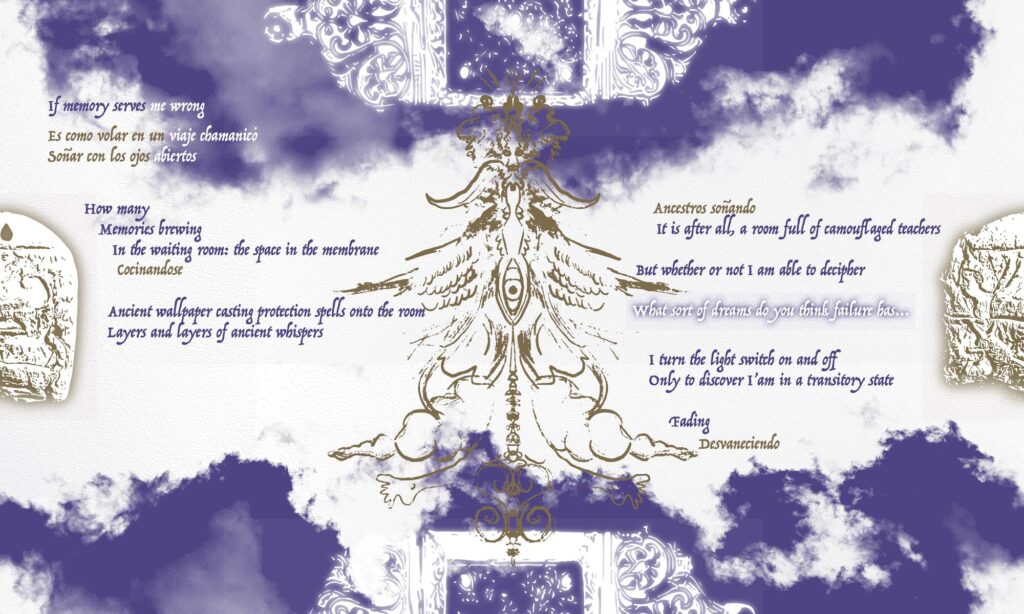

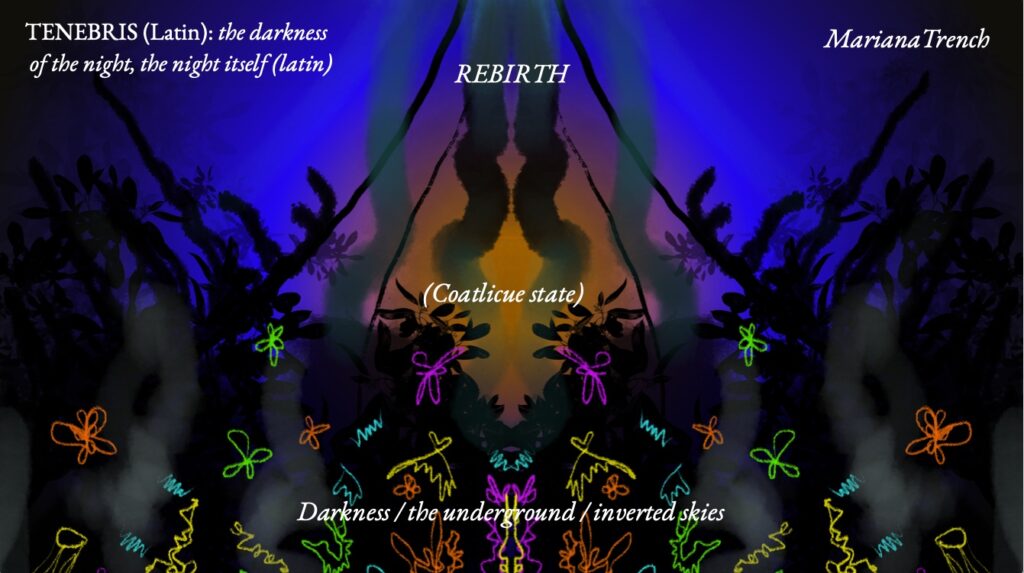

Sonda Tecnopoética emerged from a conversation with a very good friend, Darla, with whom we shared an interest in combining sound art and digital art. At that time, she was learning to use synthesizers while I was exploring the possibilities of TouchDesigner. During our chat, Darla introduced me to Vicente, who is nowadays another great friend and a fundamental part of the project. Without Darla and Vicente’s collaboration, this project would never have come to life. I deeply admire their passion and determination to achieve their artistic goals. The central idea of Sonda was to create experiences that would transport viewers to different worlds, a technopoetic exercise that explored the intersection between sound synthesis and digital art.

“The possibility of creating collaboratively with people who nurture your creativity from different perspectives is invaluable.”

We became so involved in this concept that we were invited to the Foster Observatory at Cerro San Cristóbal, to musicalize one of the guided tours of the site. We were excited and motivated as a team. Our first event was a microfestival of ambient, drone, noise and experimental music, which for me was an unforgettable experience. It was then that I realized how enriching it is to work as a team. The possibility of creating collaboratively with people who nurture your creativity from different perspectives is invaluable. After that festival, I traveled to Valencia, while Darla and Vicente continued the path of Sonda. It fills me with pride and admiration to see how they have improved their abilities to create music and sound environments. They have been invited to festivals and events, they have traveled around Chile presenting their work live and it shows how much they enjoy what they do. I look forward to meeting them in Chile and collaborating again, sharing the new things we have learned lately.

You are currently studying at LABA Valencia, can you tell us about your experience at this school and how it is helping you to channel your career, both in the contexts of design and multimedia creation as well as in the development of your artistic research?

I am currently studying at LABA Valencia, a school that I deeply admire for the quality and experience of their teachers. You can tell that they are people with extensive experience and deep knowledge in their fields. This experience has helped me to focus and find the right direction for my career. I have acquired a variety of techniques and skills that I feel prepared to apply in specific situations, and for this I am very grateful, especially to Pablo and Manuel.

In terms of my artistic research, being in an environment so different from what I was used to has challenged me to grow and study day by day to make the most of this opportunity. Although it has been a demanding and sacrificial time, I value it greatly. In addition, I have had the opportunity to connect with my classmates, many of whom have become great friends. I have learned a great deal from them, both artistically and personally. Their different points of view and experiences have helped me to broaden my perspective and grow as a person and as an artist.

This experience has led me to reflect on aspects that I had not even considered before, and has motivated me to keep moving forward on my artistic path. I am especially grateful to have won an award during my time at LABA, which fills me with gratitude and drives me to continue developing my artistic career.

As one of the winners of the SMTH and Niio open call you are going to see your work exhibited on more than 30 screens in public spaces. What do yo think of this opportunity to show your work outside the traditional exhibition spaces of the art world?

As someone with experience in the audiovisual world, where our creations usually appear on television or social networks, the opportunity to show my work on more than 30 screens in public spaces in 5 cities in Spain is simply amazing. Using my favorite techniques and tools to create this work and then being selected as one of the winners of the SMTH and Niio open call is an achievement I never imagined before coming to Spain. I am really happy and grateful for this opportunity.

I can’t wait to see how my work will look on an LED screen with that resolution. It is exciting to think about how my work will be received by the public in such a different environment than a gallery or museum. This experience allows me to explore new ways to connect with people through art and bring my work to a wider and more diverse audience. I am confident that this exhibition in everyday public spaces will be a unique and enriching experience for both myself and those who have the opportunity to see it.

“The experience of the SMTH + Niio Open Call allows me to explore new ways to connect with people through art and bring my work to a wider and more diverse audience.”

In Desvanecer we see references to Quayola’s Natures (2013) series. What other artists have inspired your work? What do you find most interesting in artistic practices linked to digital media today?

It’s curious because I didn’t know Quayola’s work, but upon researching it, I was fascinated and I’m sure it will be a source of inspiration for my future works. Besides Quayola, other artists who have deeply influenced my work are Tatsuru Arai and Ryoichi Kurokawa. Tatsuru Arai is a visual artist and sound composer who works mainly with dots and flowers, two elements that have always fascinated me and that I enjoy experimenting with. The way he represents nature in digital formats captivates me; the process of bringing something living into a virtual world, where everything is reduced to data, is an analogy that I find extremely intriguing. On the other hand, Ryoichi Kurokawa uses dots, light and glitch in his works, and I feel that each one tells a story. Coming from an audiovisual background, I really appreciate the narrative that Kurokawa manages to create in his work. It’s like watching a movie, and that storytelling ability inspires me deeply.

As for artistic practices linked to digital media, what fascinates me most is the infinite variety of possibilities they offer. With the advancement of technology, these artistic expressions have no limits. Every day I discover something new and find inspiration in the expanding community of digital artists. I love the online interaction and how people share knowledge and experiences to enhance our skills as artists. While the limitless growth can be a bit overwhelming, I see it as an exciting opportunity to explore new frontiers and expand my artistic practice.

Can you tell us about the digital art scene in Chile? What spaces or groups do you consider most relevant, and what are the challenges for Chilean new media artists?

The digital art scene in Chile is experiencing remarkable growth, with an increasing interest from both the public and institutions. There is growing interest in learning programs such as TouchDesigner, both from individuals and from educational institutions seeking to teach these skills. Museums are also recognizing the importance and potential of this expanding field, which is encouraging for the future of digital art in the country and motivates me to continue exploring and creating.

From my perspective here in Valencia, I have observed a remarkable space called Museo Interactivo Las Condes, which is standing out as an important center for digital and interactive art in Chile. In addition, there are other relevant spaces and projects such as Cimuad, directed by Esteban Fuica, a leading exponent of digital art in Chile, as well as Centro Cultural Ceina, Feria Fast and Hub Creativo, among others.

“New media artists in Chile face the challenge of a lack of formal education in this field, insufficient recognition and understanding by institutions, and funding, since some artworks can be costly to produce.”

For new media artists in Chile, the main challenges include the lack of formal education in this field, which is relatively new. Many learn these techniques through a constant effort of searching for resources and knowledge. In addition, there is a need for greater recognition and understanding by institutions, art critics and the general public of the value and importance of new media works. Finally, funding can be an obstacle, as some works can be costly to produce.