Pau Waelder

On October 29, 2024, Valencia experienced catastrophic flooding due to an isolated high-altitude low-pressure system (known in Spanish as Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altos, or DANA) . This weather phenomenon brought torrential rains, with some areas receiving over 300 millimeters (approximately 12 inches) of rainfall in a single day—equivalent to the region’s average annual precipitation. The deluge resulted in severe flash floods, leading to a death toll of at least 217 individuals (as of November 5th) and extensive property damage.

The floods in Spain are yet another reminder of the life threatening consequences of climate change, precisely because the disaster has not solely been caused by rising temperature of the Mediterranean Sea, but due to a series of factors that include irresponsible urban planning, real estate speculation, and a lack of awareness about the serious effects of an adverse climate.

In a press release launched the day after the flooding, the environmental activist group Greenpeace asked “who will pay for this?,” pointing out the responsibility of fossil fuel companies in creating the environmental conditions that now lead to such a catastrophe. Describing the effects of the DANA as a “natural disaster” diverts attention from the fact that its causes can be found not in nature, but in human activity and economic profit.

“In 2023 a new study was released indicating that the world’s top fossil fuel companies owe at least $209bn a year in climate reparations to compensate communities suffering the most harm from climate change.”

Paolo Cirio. Climate Tribunal, p.71

Addressing this economic profit, artist and activist Paolo Cirio aims to shift public perception by holding the fossil fuel industry accountable for its role in the climate crisis in an ongoing body of works titled Climate Tribunal. Cirio combines art, scientific research, and advocacy to bring forth a new cultural understanding of climate change and its ethical implications in a call for legal and moral accountability for the environmental destruction caused by fossil fuel companies. The Tribunal seeks to prosecute these corporations for what the artist refers to as “climate crimes”—the deliberate misinformation and public manipulation that has fueled decades of environmental degradation. Using historical, scientific, and political evidence, the Climate Tribunal positions itself as a platform for public discourse and action.

Cirio recently published the book Climate Tribunal. Fossil Fuels Industry On Trial, which collects a series of texts by the artists and documentation of his artistic projects. The volume, which is available as a downloadable PDF, addresses how fossil fuel corporations have strategically influenced public opinion, politics, and cultural institutions, shielding their culpability through misinformation campaigns. Cirio highlights that despite numerous lawsuits, the true scale of these climate crimes has yet to be acknowledged, with most cases focusing on financial compensation rather than addressing the deeper injustices against humanity and nature. The Climate Tribunal suggests a shift in perspective, urging global citizens to focus on those truly responsible, rather than blaming individuals for global warming.

Through artistic, legal, and ethical lenses, Cirio’s The Climate Tribunal not only presents a case against the fossil fuel industry but also challenges the art world and society at large to recognize their role in climate justice. It is a bold proposition to rethink how we engage with climate change, urging us to move beyond the abstract and into tangible action, holding corporations and systems accountable for their environmental impact.

“It was the idea of the ‘Carbon Footprint’ by British Petroleum (BP) that moralized personal ethics of climate change.”

Paolo Cirio. Climate Tribunal, p.24

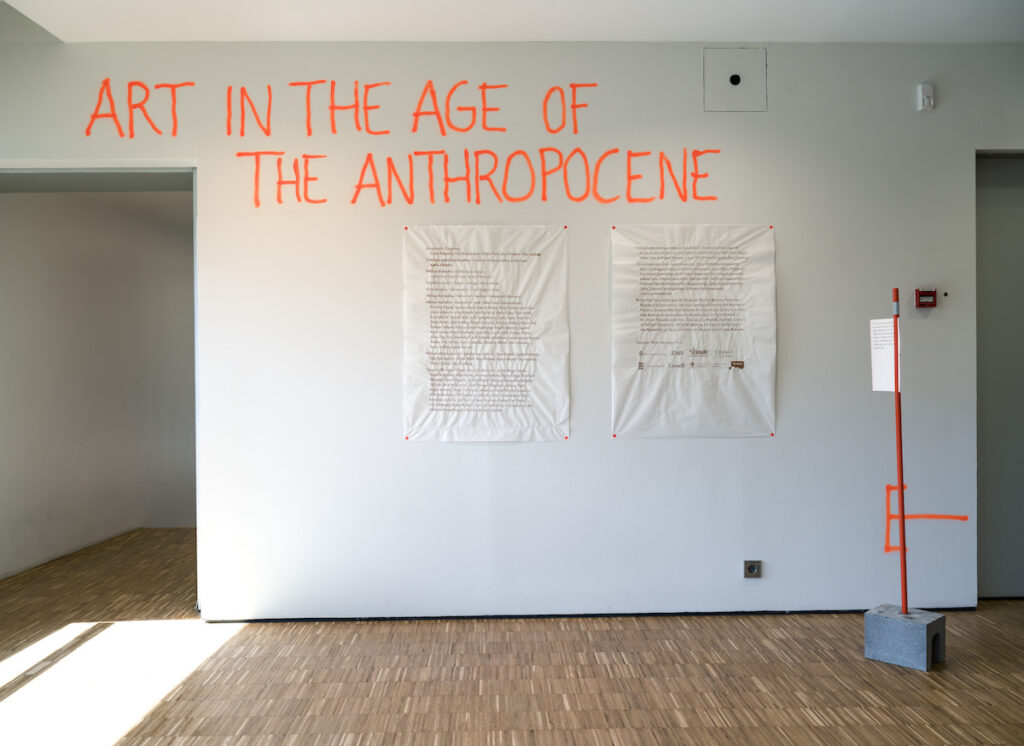

Climate Aesthetics

While it can be said that in this project Cirio bridges the gap between activism and artistic expression, his book also addresses the representation of climate change in the arts. This is not simply a question of aesthetics, but also a form of activism, since art can inspire new ideas, respond to people’s emotions, and question widespread assumptions in visually attractive and engaging ways. The “white cube” space of museums and art galleries creates a specific environment to which visitors go to pay attention to what the artists have to say, and this is a powerful context for the artworks to communicate ideas and catalyze emotions about climate change and the future of our planet.

According to Cirio, the representation of climate change in the visual arts is often “diluted within the broader discourse on the Anthropocene, remain purely scientific, merely depict nature, or just adopt defeatist attitudes.” He also points out that these vague or unrealistic messages can be part of what is often termed “green-washing” or “artwashing,” referring to the patronage of cultural events and institutions by fossil fuel companies to present a positive and relatable image to society.

“Art can play a key role in fostering the ability to see, feel, and comprehend the scale of climate change. Particular uses of semiotics and linguistics in Climate Aesthetics can make the perception and cognition of climate change accessible through emotive, compelling, and appealing works of art.”

Paolo Cirio. Climate Tribunal, p.205

The artist therefore raises the question of the ethics of art that represents climate change, asking whether by, for instance, when creating a fictional scenario, scientific facts may be altered or disguised, contributing to an increased confusion as to the effects of global warming. He also points out that “representing climate change with only data and information or with just weather events and climate anomalies might be reductive and limit signification without integrating struggles for climate justice, social inequality, and human rights.” His main point is that addressing the damaging effects of our exploitative relationship with nature should encompass all of its aspects, not just the longing for an idyllic, peaceful nature, or the catastrophic events that are happening with increasing frequency around the world, but also the causes and the role of those who contribute to climate change and even hinder any efforts to prevent it.

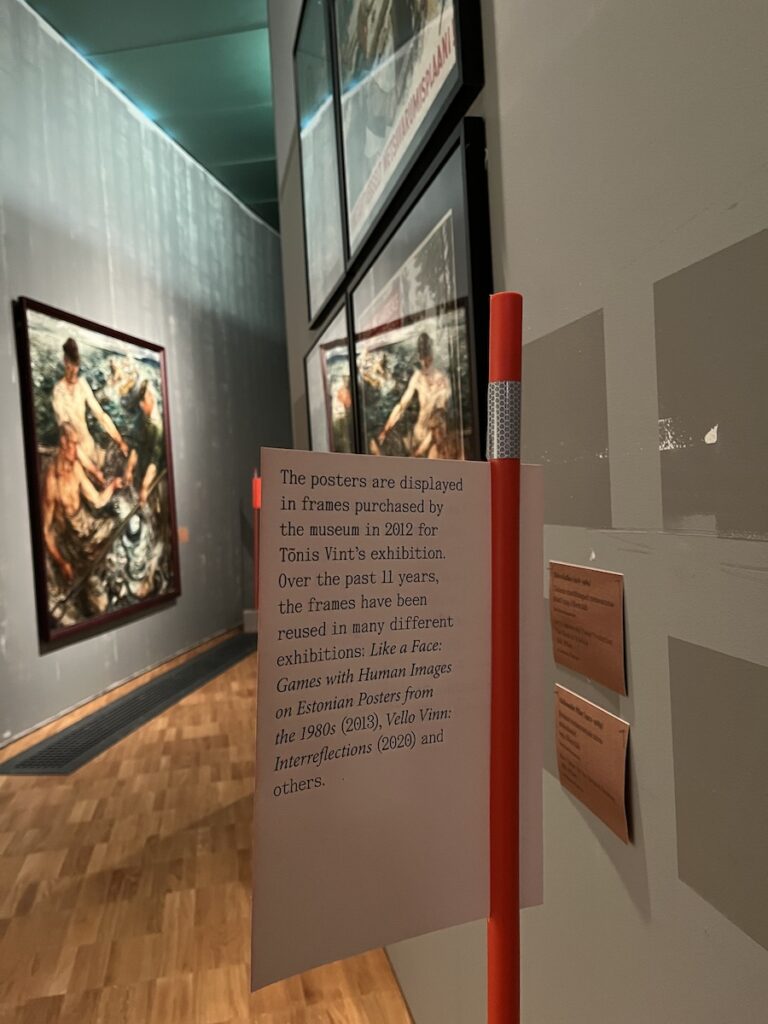

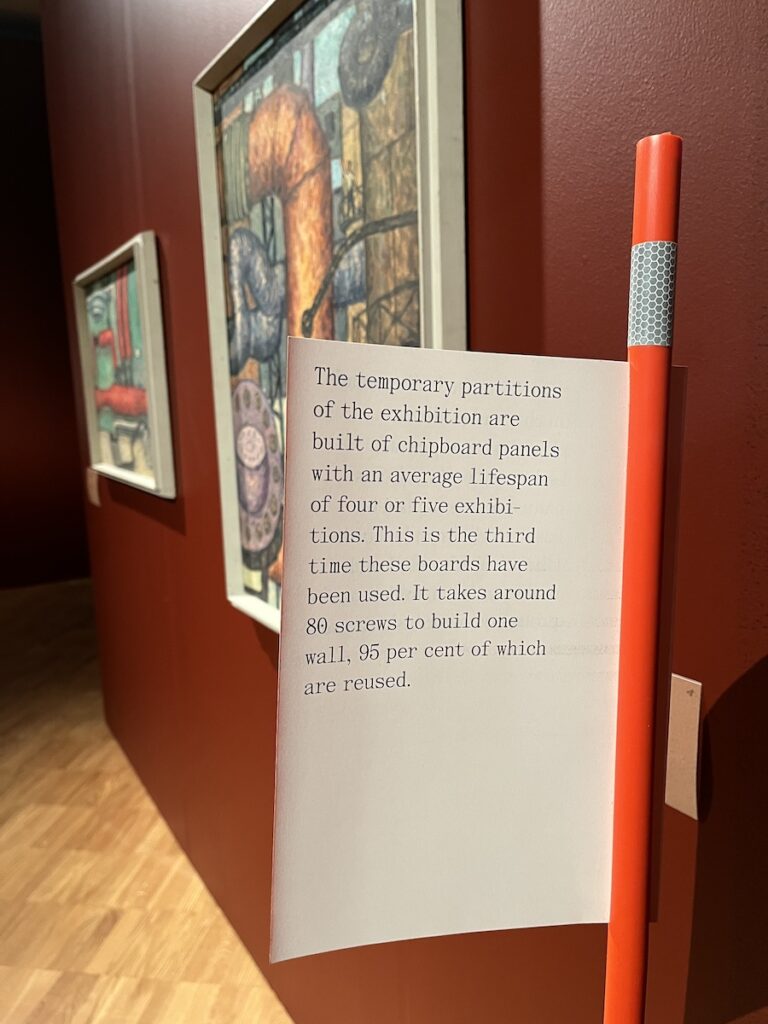

“Climate change in the cultural world is still rarely addressed as it’s a sort of inconvenient subject,” stresses Cirio. Aspects such as the “footprint” of producing artworks, shipping them to art fairs and exhibitions, or motivating individuals to travel to distant places to see art, as well as the previously mentioned sponsorship of fossil fuel companies, are part of what the art world feels guilty of in terms of their commitment to higher ethical values, the preservation of our natural environment being one of them.

At this point, Paolo Cirio suggests a series of tactics and strategies that can be applied (and are actually applied by some artists) in the context of climate aesthetics (p.213-214):

Some tactics of Climate Aesthetics

- Raising Awareness Art to inform and galvanize the audience and the general public.

- Social Commentary Art to examine political themes and document social, economic, and ecological conditions.

- Social Innovation Art to provide social solutions and adaptation to disasters.

- Monumentalization Art to remember what is lost with memorials, archives, and ceremonies.

- Mourning Art for emotional support and healing through care and empathy.

- Activism Art for campaigns and protests to bring change and justice.

Some strategies of Climate Aesthetics

- Documentary Art including documentation of causes and effects in order to inform and keep records of events and experiences which can be used in activist, journalistic, and juridical contexts.

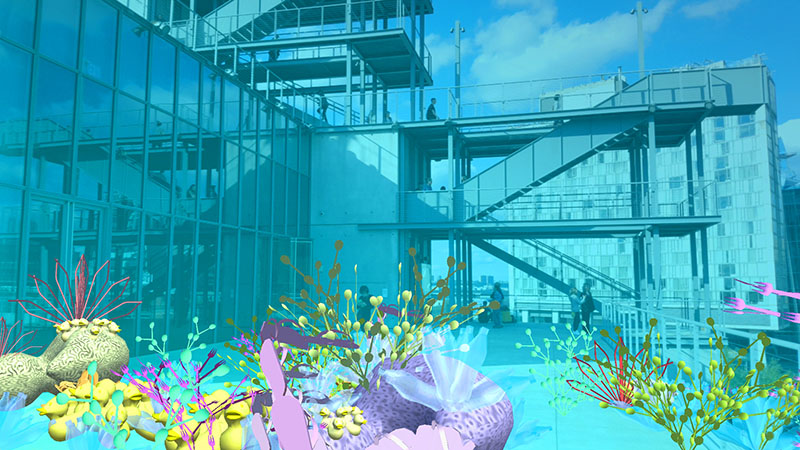

- Storytelling Art including fiction of speculative scenarios, or that integrates the causes and effects of climate change, or is based on personal and biographical experiences.

- Visual Art Art including figuration and abstraction of visual representation which can either be documentary or fiction. Any subject or issue regarding climate change can be portrayed through drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, video, imagery, data, or text.

- Social Practices Art including support to vulnerable communities and individuals through social engagement, activism, or emergency response.

- Conceptualism Art including economic and governance analysis, institution critique, or legal imagination, which overlays concepts, research, practices, and processes.

Since 2021, the artist has put these ideas into practice in a large series of artworks that combine online activism, data collection, prints, paintings, and installations and that have been exhibited in contemporary art foundations, science museums, cultural institutions and universities internationally.

Certain artworks, such as Climate Class Action (2023) or Extinction Claims (2021), are online platforms that invite visitors to claim financial compensation from major fossil fuel firms for the ways in which climate change has affected their lives, and also to present those claims on behalf of endangered species. Others, such as Flooding NYC Claims (2023), focus on a specific event and location (in this case, the disastrous floods in New York in 2023), raising awareness about the responsibility of fossil fuel companies and providing citizens with the tools and information necessary to claim financial compensation. Regardless of the fact that these claims could actually lead to legal proceedings forcing the largest polluting companies to pay large amounts of money to individuals, communities, and governments, they highlight the economic impact and motivations underlying climate change, raising awareness about the huge benefits that fossil fuel companies are making and possibly motivating legal actions or at least a change of mentality.

An important element of Cirio’s projects are the many prints, posters, and graphic materials that contribute to disseminating the messages among the population in a way that is easily accessible and that puts the message outside the context of the “white cube,” where it will be seen by an audience that is attentive, but also more interested in concepts and aesthetics and less in actual political or social action. Addressing climate change, the artist smartly focuses on the economic aspects and how people’s lives could improve if fossil fuel companies took responsibility for the effects of their activities on our environment and the way they have contributed to hinder our understanding of this issue. Footprint Justice (2023), for instance, focuses on the cost of public transportation (which is particularly felt by young people) and proposes a “utopian social movement” suggesting that everyone should have access to public transportation for free while receiving payments for maintaining low carbon footprints. Again, the implementation of this idea is hard to achieve, but the aim is actually to change people’s mindsets and consider why their efforts at being environmentally friendly are not matched by the big companies, which have the resources to make a much greater impact.

It seems like a bold statement to affirm that fossil fuel companies should compensate individuals, and even animals, for the effects of “natural disasters.” It also seems to go against the basis of capitalism that a profitable activity, supposedly contributing to the prosperity of communities and regions by generating employment and wealth, should be put on trial because of its effects on something as abstract as “nature.” Aren’t we living in the Anthropocene? Isn’t this our time to rule the Earth? Certainly, many might feel skeptical about the ideas that Paolo Cirio puts forward in these projects, and even the data he aptly shares for anyone interested in digging deeper. It might seem inconceivable to question the ethics or confront the power of these companies, let alone to imagine a society that does not depend on fossil fuels. But to address the inconceivable has often been the task of artists, sometimes under the guise of irony, speculation, or simply fiction. The Climate Tribunal artworks confront us with an issue that is both hard to understand and to assimilate. It is our choice to take action or look away.