Pau Waelder

Paris-based artist Antoine Schmitt describes himself as a “heir of kinetic art and cybernetic art,” aptly indicating the two main aspects of his work: the interest in all processes of movement, and the use of computers to create generative and interactive artworks. With a background as a programming engineer in human computer relations and artificial intelligence, his career spans almost three decades and is characterized by a combination of interactive installations, process-based abstract pieces, and performances. He has collaborated with a wide range of professionals from the fields of music, dance, architecture, literature, and cinema. He also performs in live concerts and writes about programmed art.

Schmitt’s award-winning artworks have been exhibited internationally, in prestigious venues such as the Centre Georges Pompidou and Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and world-renown festivals Sonar (Barcelona), and Ars Electronica (Linz). A selection of video recordings from his generative works have been featured in our curated art program, including the artcasts Unvirtual Art Fair (Paris) and Possibles, which was exhibited at the ISEA2022 Barcelona Symposium. The artist kindly answered a series of questions about the concepts and processes behind his work.

From your early works to the latest installations, there is a constant interest in the relationship between the artwork and the viewer, and more generally between a human and a machine, that often become intimate, connected to emotions and to physical proximity. What do you find interesting about this strange relationship between an individual and a machine, or an apparently sentient entity?

Programming has always been for me a means to approach reality, by recreating it. I consider programming as a radically new material, in art and in general, because of its active nature: programs are processes embedded in reality and can react to it and act upon it. This specificity allows me to recreate programmatically aspects of nature that interest me. One of the most complex entities in reality (known so far) is the human being. Many of my artworks stage a programmed artificial entity that embodies a deep aspect of human nature. These artworks act for me as mirrors for the viewer, a way to question deep human mechanisms or ways of being, like desire, curiosity, language, conflict, gravity, etc… not forgetting that humans are also animals, and are also bodies in space.

This approach also allows me to reflect on the way we humans are programmed, by laws, evolution, society, etc… My artworks are, like deep science fiction, very much fueled by philosophy, physics, metaphysics, sociology, psychology, anthropology, etc… Using programming to create artificial entities, more or less intelligent, more or less sentient, but all embodying dynamic aspects of human life, allows me to focus each artwork on a specific concept or aspect of human nature. They are forms of living caricatures that are all the more effective.

“I consider programming as a radically new material because of its active nature: programs are processes embedded in reality and can react to it and act upon it.”

Your work is characterized both by its interactivity and the generative processes that bring it to life. What do you find most interesting about these two types of processes, the one carried out by an autopoietic generative artwork and the one carried out by an interactive installation?

All my artworks are active and exist in real time, i.e. the same time as the spectator. Some artworks are not sensitive to the real world, they are not interactive, they live their life in their own universe, and we watch them like we would watch a strange animal in an aquarium. With these artworks, the main link between the audience and the artwork is through empathy. By projecting oneself in the existential universe of the artwork, the spectator recognizes and feels the situation. It is the same process as with movies and books, with the additional dimension of the real time: with realtime artworks the spectator knows, or feels, that what happens happens here and now. It is not a recording. This gives a different dimension to the empathy, like when watching a live performance which also happens here and now.

With interactive artworks, I usually want to question the behaviors and inner mechanisms of the audience themselves. It is the actions of the viewer which are the artwork, I create the dynamic situation in which the viewer is immersed and I orient it so as to highlight and question certain deep ways of being. For example, the Systemic (2010), Lignes-mobiles (1999) and La chance (2017) installations draw dynamic arrows on the floor in front of passers-by to question their intention. In Psychic (2007), a text on the wall describes the movements and intentions of the spectators in the exhibition space (“Somebody is coming”).

I tend to adopt a minimalist approach: I don’t use an artistic dimension (color, figure, interactivity) unless it is mandatory for the artwork. So I don’t use interactivity unless the artwork’s subject is the spectator themselves.

“In my interactive installations it is the actions of the viewer which are the artwork, I create the dynamic situation in which the viewer is immersed and I orient it so as to highlight and question certain deep ways of being.”

Since the beginning of your career, you have collaborated with performing artists, among which composers such as Vincent Epplay, Franck Vigroux, and Jean-Jacques Birgé, performers such as Hortense Gauthier, and choreographers such as Jean-Marc Matos and Anne Holst. How did these collaborations take place? What have they brought to your own work and your creative process?

I have two different approaches to performance, whether I’m on stage or not. When I work with professional performers who use their body and actions as their main material, we craft situations where the human entity is confronted to an artificial one. This allows us to precisely stage the encounter and focus precisely on certain aspects, which become the subject of the performance. The situation usually centers on the concept of an encounter with an “other” and on the modalities of dialog. In Myselves with Jean-Marc Matos, it is about exploring various modes of dialog like imitation, fight or fusion. In CliMax with Hortense Gauthier, it is about finding mutual pleasure. In these setups, the mirror effect happens between the performer and the artificial entity rather than with the audience. The audience is watching the encounter. The artificial creature becomes an actor of the performance, in the spirit of performance: taking risks in a staged delicate situation.

Antoine Schmitt and Hortense Gauthier. CliMax (Préliminaires), 2018

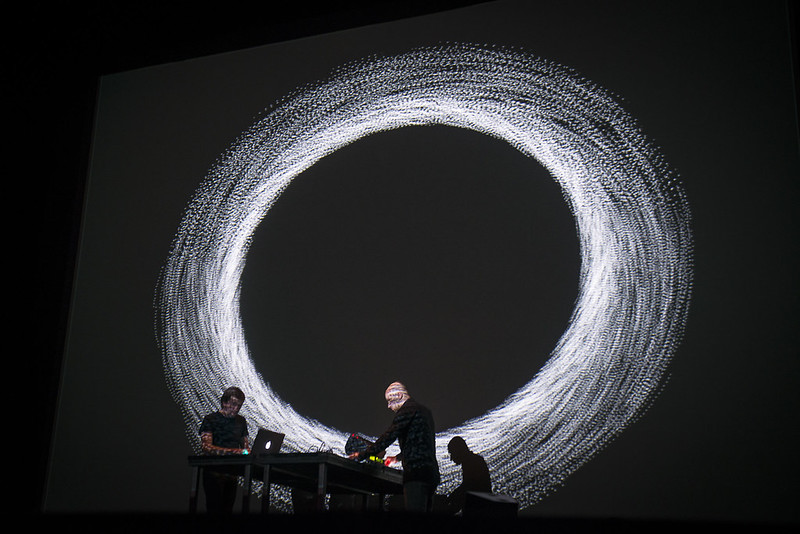

When I am on stage, I usually play live images, using a videogame-like visual instrument that I program myself and that recreates a specific abstract though consistent live universe, while the other performer plays live music. We are in a situation of semi-improvisation and we create an audio-visual temporal exploratory journey around a specific theme (the birth of shapes in Tempest, the cohabitations of multiple timelines in Chronostasis, totalities in ATOTAL, flows in Cascades, etc…). As a performer, I appreciate sharing the energy of the present moment with the audience, especially while being delved into an artificial universe and struggling with it, which the audience can feel.

Antoine Schmitt. Generative Quantum Ballet 21 Video Recording, 2022

Besides the performing arts, another strong reference in your work is scientific research: you often mention theories from mathematics or physics as the conceptual ground for your pieces. What does science bring to your work? How do you build a bridge between the scientific method and your creative process?

I am very sensitive to the deep and strong laws of the universe that math and physic theories can give us, as they allow me to both approach our reality and imagine other possible realities. What is interesting with these laws is that they are programmable so I can recreate them using programs, thus focusing on deep mechanisms, to stage them or alter them. For example, in the Tempest show, I created a universe containing many of the forces of our universe but also invented forces, thus opening the doors to parallel universes.

I often say that science and art are interested in the same subject : the crack that exists between reality and our abstraction of it. This crack is our curse as human beings. Animals do not feel this pain but as soon as one has the gift of abstraction, the distance between what we abstract and what is, is the source of all mental suffering. Science tries to close that crack by explaining as much as possible through theories and language, more and more precisely, even though it is an impossible task (as was demonstrated in the 20th century by the scientists Heisenberg and Gödel). On the contrary, Art delves in the depths of the crack, exploring all its modalities, playing with all the emotions that stem from it. And the narrower the crack, the deeper it is.

“I often say that science and art are interested in the same subject: the crack that exists between reality and our abstraction of it.”

The aspects of your work that we have previously addressed all point to a main subject which are the processes of movement, as clearly highlighted in your artist’s statement. These processes are explored in a wide range of contexts, from the quantum realm to urban societies, and among different actors, be it people, bodies, or particles. Why are these processes so important to your work, and which of these contexts is more rich, engaging or interesting to you?

I think that I’ve always had this abstract approach to reality which can be synthesized in the question “why does it move like this?”. I started with a rather scientific approach through my studies as an engineer, and when I decided to become an artist, I continued to explore this question in a different way. It is an analytical approach, a way of looking at the world, and a way to question it. I frankly appreciate all the dimensions of it and will continue to explore them, but I think that the strongest and the ones that give me the biggest satisfaction are the most abstract approaches, the ones that are the most remote from reality and still apply to many aspects of reality, existing or perceived. Black Square (2016), where a flock of white pixels try to enter an invisible square and bounce on it thus revealing it, can lead to multiple interpretations. It is a fundamental delicate situation.

Antoine Schmitt. Black Square Video Recording, 2016

The signature element in your work, the pixel, is introduced in Le Pixel Blanc (1996). There, you describe it as “a minimal artificial presence… something that almost did not appear, but that still would be «there».” Over time, the pixel has gained more presence and become as much an object, a presence, and an absence, as part of a flow or the representation of an individual. How would you describe the evolution of your conception of this basic element and its influence on your work?

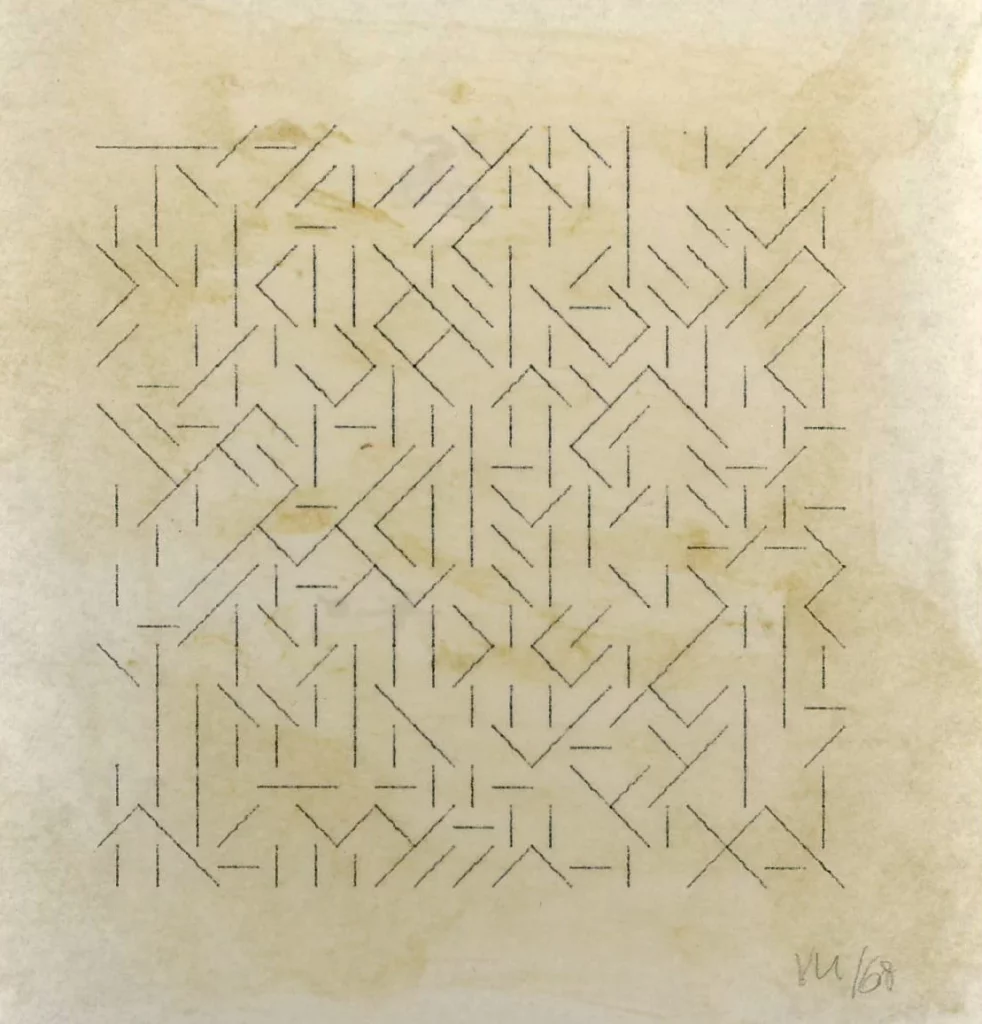

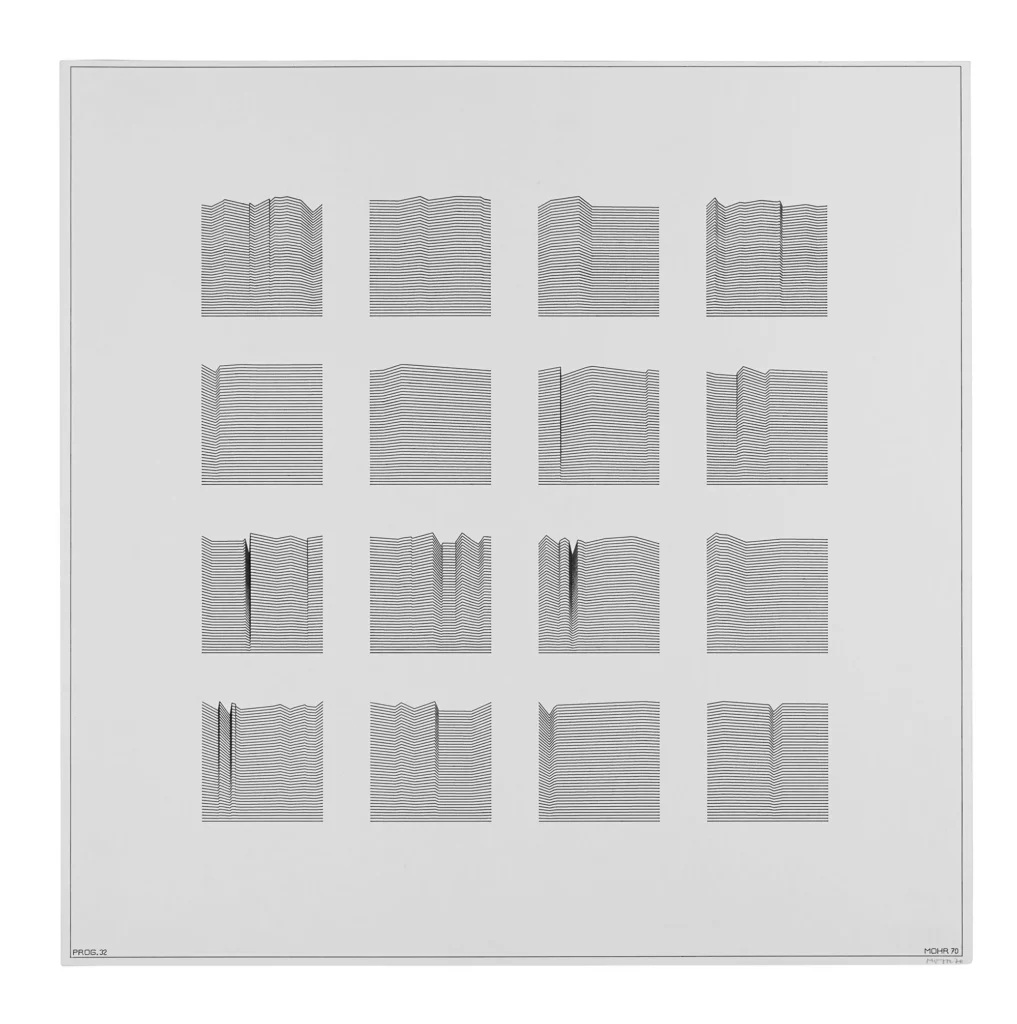

The pixel and the square are omnipresent in my work. I like my artworks to be minimal, like mathematical theorems. This naturally led to the pixel, the minimal visual element in the universe of the computer. A pixel is a small square, and by enlarging it, you get a large square. And like Malevich, I consider the square like the symptom of the human being’s power and curse: the ability of abstraction These two elements are the basis of most of my artworks. What I work on is their movement, relatively to the space around them, or relatively to the other elements. They are minimal but open to all the possibles, through their movements and the infinitely rich possibilities of programming.

“The pixel and the square are minimal but open to all the possibles, through their movements and the infinitely rich possibilities of programming.”

Your career spans almost three decades, in which you have explored many different formats of creation and distribution, from multimedia projects on CD-ROM, to Internet-based artworks, interactive installations, video mapping, screen-based pieces, software art, live performances, generative cinema, NFTs, and much more. What is your opinion on the way technology has evolved over these decades and how it has influenced art making? How have you experienced this period of constant innovation and obsolescence?

These have been very exciting years, for one because computers are more and more pervasive (we all now have a powerful computer in our pocket) and also because art made with computers is now widely accepted. It is therefore easier to create programmed artworks and to show them. The technology is more easily available, the distribution channels — in the wide sense — are numerous and the audience is listening.

On the other hand, technology is nowadays mainly used for advertising, surveillance, entertainment and manipulation of opinions, which is a social problem and has an effect on art made with technology. Many approaches build upon or react to these social dimensions, which are all needed and interesting but leave little room for the more conceptual and radical approaches. This may be true for all forms of art, but it is stronger with technological art as technology so much shapes our society these days.

What is interesting also is that I think that no new concept was really born in the field since Alan Turing invented the computer, the “universal machine”. All computer-based technologies are avatars of this unique concept. This can probably account for the fact that my artworks have not radically changed since I started. My work does not reflect on the social impacts of technology on society, nor are impacted by the various technological “innovations” and obsolescence. It is minimal so does not make use of the innovations toward more “power”, and it is rather rooted deeply in the concepts of the universal machine which have not changed : with a universal machine, all thinkable processes are programmable.

“Art made with technology often builds upon its social dimensions, which are all needed and interesting but leave little room for the more conceptual and radical approaches.”

You were already working with generative text twenty years ago, in The Automatic Critic (1999). What is your opinion about the current trend among artists to use machine learning models such as ChatGPT?

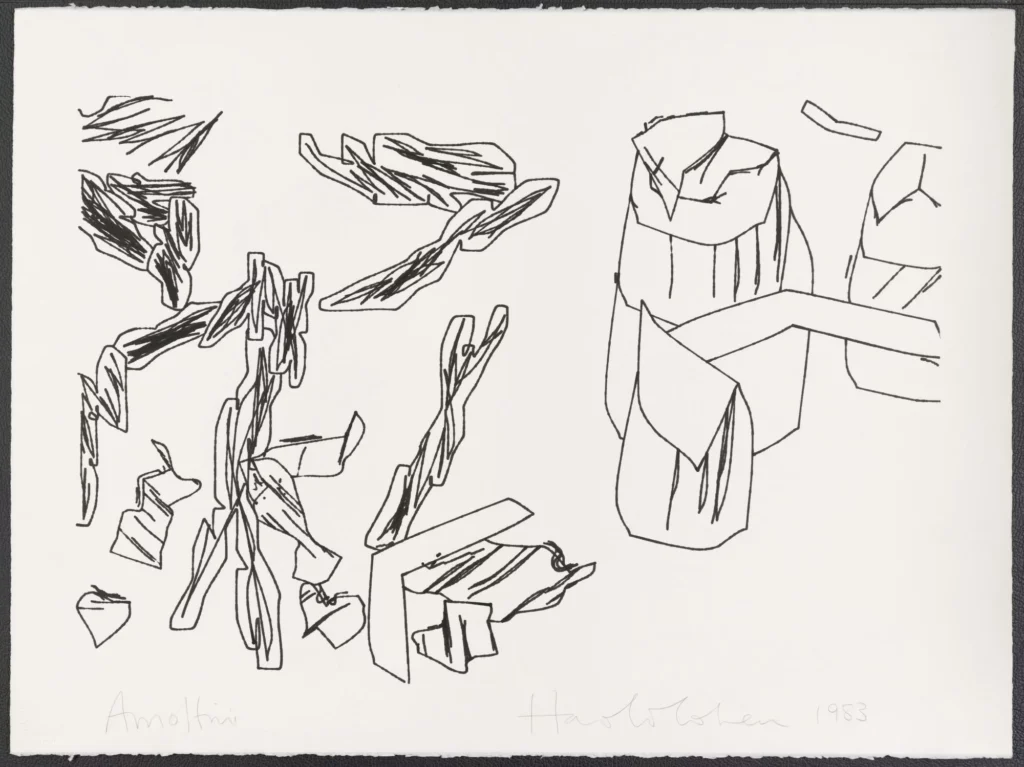

Although I am quite impressed by the quality of the interactions of users with ChatGPT (I thought that this level of quality would take more years to happen), the generative approach on these systems are in the normal continuation of the original concept of the computer. We are at the stage of imitation: these algorithms generate media that look like media created by humans, as the central mechanism of neural networks is pattern recognition and pattern generation, whether it is text, images, music, reasoning, etc… This is quite fascinating for users and it is similar to the caricatural mirror effect that I was referring to at the beginning. The art, or more generally the forms of expression, created by these algorithms in imitation of ours are a mirror to our forms of expression and thus question them.

But art is intention and responsibility. These two notions are still unique to humans. But maybe one day, we will be able to create an algorithm able to feel pain, express it with intention towards its fellow humans and take responsibility for it. There is no theoretical impossibility for this in the theory of the universal machine and I look forward to it.

In the meantime, as an artist, the most interesting aspect of AI systems remains for me the creation of biased algorithms which focus on some dimension of human nature, like Deep Love (2017) which answers all questions with “I don’t know, but I love you.”

You entered the NFT scene in 2021 with Buy Me! a particularly conceptual, and generative piece. What has the NFT market brought to your practice? Has it influenced your production? Have you found new forms of creation or sources of inspiration, beyond its commercial dimension?

It took me some time to understand that the main new concept behind the NFT market boom was the perspective of financial profit, for collectors and for artists. This is the reason I created the satirical piece Buy Me! (2021), which embodies an algorithm desperately trying to convince its viewers to buy it, using language techniques inspired by advertising and psychological manipulation. It is a piece on the processes of marketing.

Apart from greed, the NFT market has opened the field of computer art to a new audience, which was really interesting, but I am eager to see the fusion of the traditional art market with NFT seen as a new way to buy and collect artworks.

You recently quoted the mathematical theory of catastrophes to describe the year that has begun and may bring sudden change, positive or negative. How does this year look for you? Which upcoming projects can you share with us?

I am very excited to start a collaboration with the DAM Projects gallery in Berlin. Its owner, Wolf Lieser, has been involved in computer art for a few decades and I look forward to working with him and his team. We will start with a solo show next autumn, with a selection of historical works and new artworks.

I am also very excited by two new live audiovisual performances, Videoscope and Nacht, with Franck Vigroux, which are in the making, and that will tour the world along with the existing performances (Melbourne, Gijón, San Francisco, etc..).