Pau Waelder

Chun Hua Catherine Dong, Meet Me Halfway – part 1, 2021

A performance and conceptual artist whose work spans different media, Chun Hua Catherine Dong successfully navigates the space between an artistic practice characterized by the physical, bodily presence of the artist in the same space and time as her audience, and another one based on the mediation of digital technologies and a distributed and almost immaterial existence. Dong has taken her performance artworks worldwide, combining action with documentation in the form of photographs and videos that often become artworks on their own. She is also exploring the creative possibilities of VR, AR, and Artificial Intelligence in a series of artworks that are still deeply rooted in her research on gender, memory, identity, body, and presence.

Dong has exhibited their works at The International Digital Art Biennial Montreal (BIAN), The International Biennial of Digital Arts of the Île-de-France (Némo), MOMENTA | Biennale de l’image, Kaunas Biennial, The Musée d’Art Contemporain du Val-de-Marne in France, Quebec City Biennial, Foundation PHI for Contemporary Art, Canadian Cultural Centre Paris, Museo de la Cancillería in Mexico City, The Rooms Museum, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, DongGong Museum of Photograph in South Korea, He Xiangning Art Museum in Shenzhen, Hubei Museum of Fine Art in Wuhan, The Aine Art Museum in Tornio, Bury Art Museum in Manchester, Art Museum at University of Toronto, Varley Art Gallery of Markham, Art Gallery of Hamilton, among others. She is represented by Galerie Charlot in Paris.

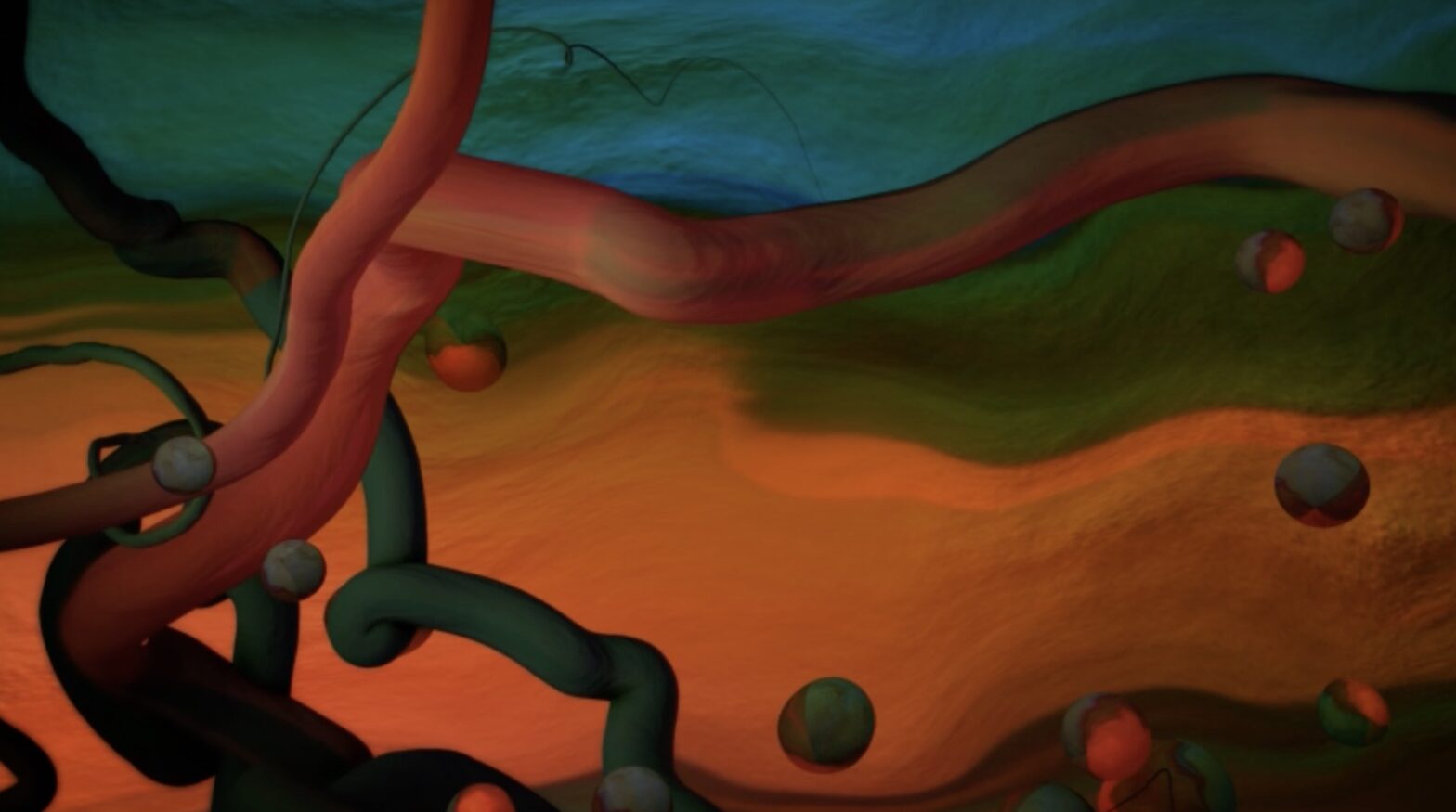

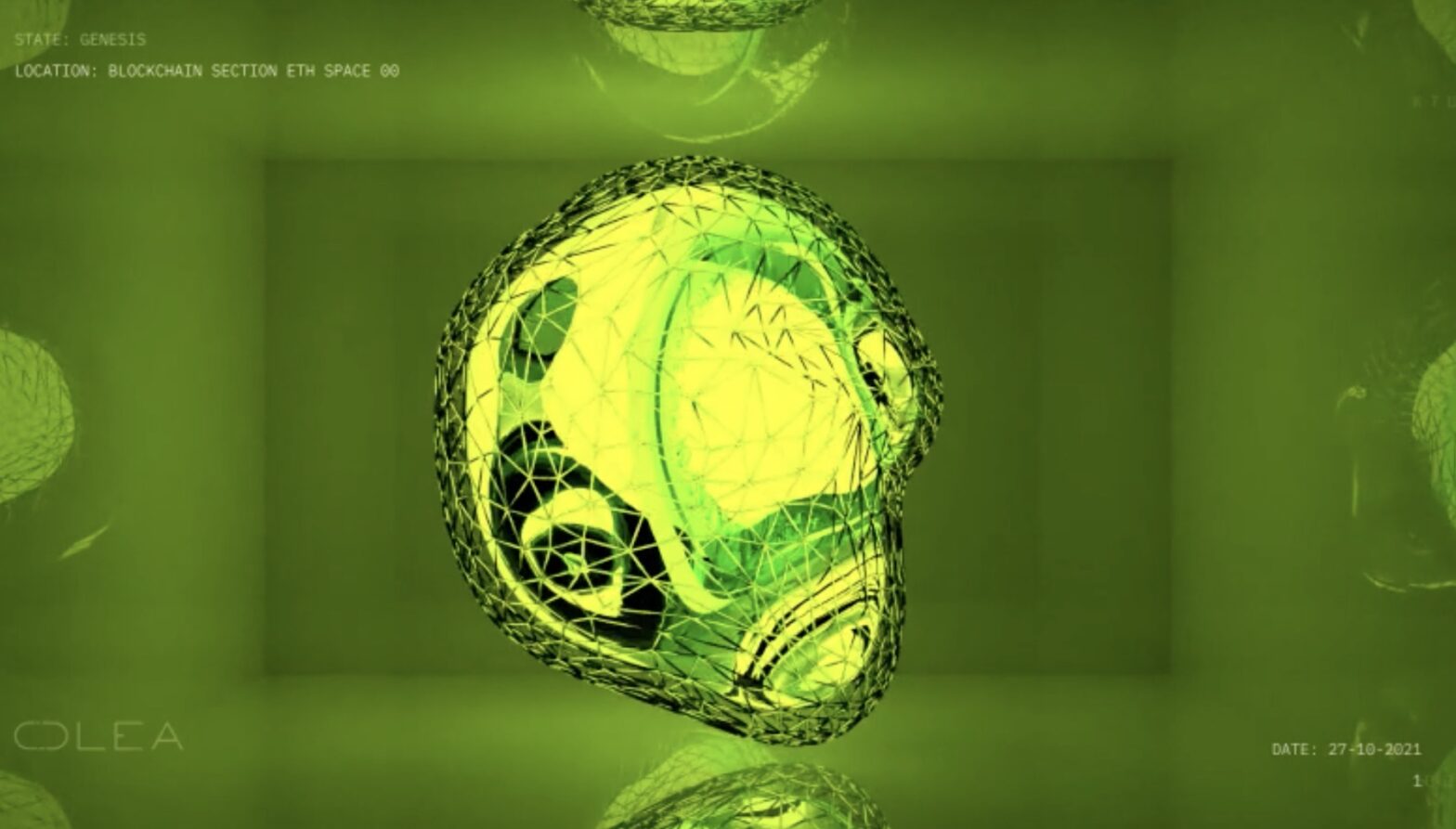

The artist recently presented the artcast Meet Me Halfway, which collects four videos from her multi-channel VR video installation that explores the perception of time and space in virtual reality and the inability to return to the present from searching the inner world.

Experience Chun Hua Catherine Dong’s immersive VR spaces in Meet Me Halfway

As a Chinese-born, Montreal-based artist, the issues of identity, culture, belonging, and distance are present in your life and your work as well. In our globalized world, these issues can sometimes be overlooked, or else exoticized and clichéd, even demanding of an artist with a mixed cultural background to address them. Would you say that there is still a dominant Western perspective on multiculturalism, and if so, how do you address it in your work?

This is a very interesting question. I can’t speak for others, but it’s natural for me to explore these topics. Living in a different cultural context often prompts questions about one’s identity. If I lived in China, I would probably never feel the need to deal with these difficult issues. But I immigrated to Canada a long time ago. I need to reconnect with my roots because I feel that something that nurtured me has faded and been forgotten. It is important for me to renew it from time to time. I addressed this issue in my earlier performances. For example, in my performance The Lost Twelve Years (2015) I use a Chinese teapot to pour ink over my head and a squirt gun to shoot ink to my heart and head, which are actions that force me to remember who I am.

“After living as a «living sculpture» for a long time, I came to the conclusion that it is wise to keep life and art separate. Now, I state that «I use my body as my material in my artwork» rather than «my body is my artwork.»”

Your body is a key element in your work, both as “the body of the artist”, representing you as an individual and your personal experiences, and as “a female body,” addressing issues of the representation of women in a patriarchal society. When you conceive your performances, how do you weigh these two possibilities?

As a performance artist, my “body as an Asian woman” and my “body as an artwork” frequently change. When I first started doing performance, I considered performance as an attitude, and that “life is a performance, performance is life.” The two were inseparable; thus, my life was always in a performance/artwork mode, or “living sculpture” mode. But I realized that I was quite weary of being my own artwork. It is also harmful to one’s mental health and sanity because the concept “life is art and art is life” could mess up your life. After living as a “living sculpture” for a long time, I came to the conclusion that “Life can be a performance, but performance is not life—at least, not my entire life.” It is wise to keep the two separate. Later, I use the statement that “I use my body as my material in my artwork” rather than “my body is my artwork.”

In your work, we can find on the one hand a direct approach to the body, naked, as a canvas or an object, and on the other hand the body veiled by masks and disguises. What do you find more interesting about playing with the different levels of displaying and hiding the body, maybe also seducing or unsettling the viewer’s gaze?

This is a very interesting question. Yes, there were naked bodies in my early performance work. For me, the body is a blank canvas, and any type of clothing or even makeup can give “identity” to it. Perhaps viewers perceive me as vulnerable when they see me naked, but I don’t feel that way. Being naked doesn’t challenge me but rather challenges the viewers. The power of the naked body in performance art lies in its rawness, it’s a pure form of art. Anyway, who isn’t born naked?

“For me, the body is a blank canvas: any type of clothing or even makeup can give “identity” to it. Being naked doesn’t challenge me but rather challenges the viewers.”

In the digital world, physical distance, the presence of the human body, and even identity tend to be blurred or seemingly erased. For instance, your work Meet Me Halfway is strikingly different from your performance work in both aesthetics and the presence of the body, yet you have incorporated your body in the form of camera movements. How do you navigate the differences between an immaterial digital environment and the materiality of your performances?

Meet Me Halfway (2021) was created during the pandemic. According to reports, many Asian people were attacked in public places during the pandemic. I was afraid of going out. If I had to go out, I wore a big hat and mask to cover myself because I didn’t want to be recognized. This situation subconsciously influenced my work Meet Me Halfway, which is why my body is absent in this work but just camera movements. I became interested in VR during the pandemic as well because I discovered that VR can help me to escape from reality. VR space is less political, at least, you won’t get physically attacked. You can build your own virtual world in VR and visit it from time to time whenever you want. It is interesting that you mentioned immateriality in the digital environment. Actually, performance art is often regarded as an immaterial practice as well. Because of its immaterial nature, it is very easy for me to shift my practice from performance art to digital art.

Chun Hua Catherine Dong, Mulan (2022)

Following with the previous question, Mulan addresses gender identity through a folk heroine placed in an underwater landscape. What seems at first a scene of pure fantasy contains numerous symbolisms. How would say that a viewer immersed in this VR space can connect with the message you want to convey?

Gender is an important component of my work. Mulan (2022) was inspired by Beijing Opera. You are right. “Mulan” depicts a pure fantasy scene because Beijing Opera is my fantasy. I used to dream of wearing the Beijing Opera costume and performing on stage when I was little. But Beijing Opera is a form of high art, not many people have a chance to access it. For me, art provides a space for asking questions and discovering; I’d be very happy to see that people have questions when they experience Mulan, such as, “Why Mulan? Why are there two Mulan? What outfit does Mulan wear? What are the names of the sea creatures surrounding Mulan?” If people ask questions, they will find answers. Sometimes I realize that I am more interested in how viewers feel and think about my work rather than telling them what my work is about. Viewers’ different interpretations enrich and expand the artwork itself.

“I am more interested in how viewers feel and think about my work rather than telling them what my work is about. Viewers’ different interpretations enrich and expand the artwork itself.”

The mise en scène is an important element in a performance, which in your work translates to carefully set up photographs, installations, and VR environments. What is the role of space in your work across the many different media you use?

Mise en scene is a stage. Most of my works are staged. In performance, “mise en scene” can be in any place, including public, private, virtual, or imaginary spaces. Camera frame is a type of stage too because activities must occur within the frame in order for the camera to capture them. If we apply this concept to traditional art, a plinth is a stage for sculptures, and a wall serves as a stage for two-dimensional artworks.

You have stated that you initially wanted to become a painter, but found that performance was more expressive. Yet there is a painterly quality to much of your work, particularly in photography and digital art, besides the use of paint in some of your performances. Which would you say is your approach to painting nowadays?

Yes, I wanted to be a painter before. But painting has its own limitations because you work in a two-dimensional space, and you must sometimes wait for it to dry before applying another layer. Performance is an expressive medium, I never wanted to go back to painting after I fell in love with performance. My work does have painterly quality, I guess it is because of my painting background. Regarding how I approach painting nowadays, I think it is VR drawing/ painting. It doesn’t limit you in a 2D space like traditional painting, but rather you work in a 3D space. When you draw a line in VR, it is a 3D line, and you can zoom in and out to see your drawing/painting in 3D perspective, which fascinates me.

“I approach painting through VR. It doesn’t limit you in a 2D space like traditional painting, but rather you work in a 3D space. When you draw a line in VR, it is a 3D line, and you can zoom in and out to see your drawing/painting in 3D perspective, which fascinates me.”

In your recent work Out of the Blue, you address your childhood and feature a teddy bear character that has been present in your work over the last three years. Can you tell us more about this character? You frequently use 3D printing techniques to create sculptures, why have you chosen this technique over more traditional forms of modeling and sculpting?

The teddy bear is a symbol of childhood. With its eyes closed, the bear refuses to look at the world, rather prefers to dream. In my digital art practice, I began with AR and VR, and then 3D printing. It is very natural for me to use 3D printing to make sculptures because 3D printing is a type of digital fabrication. 3D printing is also a practical choice. Traditional sculpture requires a large studio space and special tools, which I don’t have. On the other hand, 3D printing doesn’t require much space; simply having a table or a desk at home is sufficient. Traditionally, 3D printing has been used to make molds or prototypes for further work. However, I embrace its rawness. I use 3D printing as the raw material for my finished artwork, with no additional touches such as sanding or painting. The unpolished raw nature of 3D printing fascinates me because it captures the essence of the technological and digital process, demystifying how artwork is made.

You have recently started experimenting with AI, first in the photographic series For You I Will Be an Island, and lately creating animations of what appear to be underwater creatures. Can you tell me about your experience with this technology? Which are your objectives when using AI programs? How does working with these programs differ from your VR and 3D animations?

I like AI. For me, AI is more than simply a tool; it’s like having an assistant. I understand that people have concerns about AI. I completely respect that. However, as an artist with limited resources and financial assistance, AI helps me save time and money when creating artwork. For example, in For You I Will Be an Island (2023) I printed 23 pieces of 2.5 m x 2.5 m AI generated graphics; I can’t imagine how I would do this without AI. I could paint 23 pieces of 2.5 m × 2.5 m paintings, but how long would it take? Or I could use photographs, but where would I find such locations to photograph? I probably can find them if I have the financial freedom to travel around the world to look for them, but how long would it take? Now AI is able to create animation and 3D objects, although it is not there yet, it is still very exciting. Animation and 3D modeling are often very time consuming and costly. If I have a budget, of course, I prefer to work with creative people, but if I don’t, AI is a good way to go.

Chun Hua Catherine Dong, For You I Will Be An Island (2023)

As we are starting the year (in the Gregorian calendar, and soon the Chinese New Year), it begs the question: what are you currently working on, and which projects do you have in store for the coming months?

Thanks! I am very excited that the Chinese New Year is coming soon. This is the year to celebrate the dragon. I am currently working on a public art project with 35 video displays at Place des Arts in Montreal. I am also working on an upcoming solo exhibition at Galerie Charlot in Paris in April. And I will participate in Montreal’s International Digital Art Biennial (BIAN) in May.

“If I have a budget, of course, I prefer to work with creative people, but if I don’t, AI is a good way to go.”