Pau Waelder

Spanish new media conceptual artist and researcher Solimán López has developed over the course of a decade and a half a body of work that connects contemporary art with scientific research, 3D imaging, geolocation, biotechnology, and lately blockchain and web3.0. An indefatigable experimenter, he has explored numerous technologies to create his artistic projects and always kept a connection with traditional techniques such as painting and sculpture, although reconfigured through digital imaging and computer-aided manufacturing.

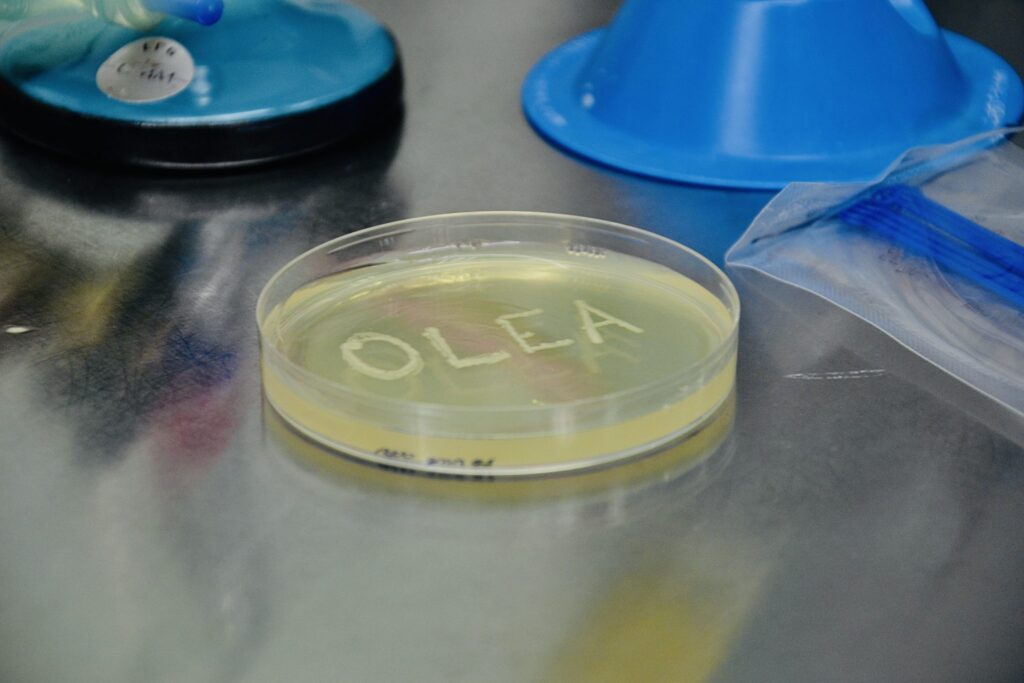

The artist recently presented on Niio several artworks related to OLEA, an ongoing project that consists of the production of a substance composed of olive oil that contains the code of a smart contract, synthesized in DNA. Solimán has created a number of NFTs and installations around the concept of OLEA. In the following interview, he elaborates on the making of this project and the main themes he addresses in his work.

Explore the visualizations of OLEA on Niio

Solimán López, OLEA Genesis Space, 2023

Throughout your career you have used a wide variety of technological resources. How have they influenced the development of your work? Has it been technology that has inspired the creation of a work, or have you sought the necessary resources to carry out an idea you had developed? Or has it been both?

My background is in art history. That is why I have finally become what we could call a “new media conceptual artist”. This means that I consider my work to be essentially conceptual. During my training I quickly understood that much of the relevance in today’s artistic discourses can be found in uses of technology because of its social, ethical, moral and sensory impact. In order to talk about the changes derived from this revolution, I also understood that it was necessary to know very well its origins, motivations and functioning logic, and that is why I started doing research on different new technologies, thinking that their understanding would allow me to make poetry, as the poet does with words.

“What is clear to me is that a good concept ages better than any technique.”

For this reason, my use of technology is always subordinated to a particular idea that I understand is expressed in a successful way with those means. But at the same time, there is a sort of parallel learning about the message and techniques. Nowadays it is difficult to choose the technique with which something makes sense, since there are a great number of formats that are beginning to be accepted. What is clear to me is that a good concept ages better than any technique and that, together with other professionals in the sector, I think that in new media art, the artworks are generated every time they are exhibited, since technically they are running on software and hardware.

It is perhaps for this reason that some obsessions I have with the materiality of the digital arise, issues that we see very evidently in projects such as the Harddiskmuseum or OLEA.

Solimán López, OLEA Space 01, 2023

Your previous work has focused on data collection, geolocation and data storage in relation to the concept of memory. How does OLEA relate to these concepts?

OLEA is becoming a whole universe in itself! It has opened up a Pandora’s box of conceptual possibilities. With the passing of time, I myself have been surprised by the way in which my works fit together in a discourse that makes a lot of sense to me. The obligation to have a “style”, which worried me when I was younger, has simply become a set of features and themes that naturally emerge in my projects.

OLEA relates to the storage of data as it is actually code stored in DNA and then preserved in olive oil. It is also a time capsule, in this case related to the evolution of the concept of value in the history of mankind and the understanding of data, which now encompasses genomics. Human beings have left traces throughout their evolution, and let’s not forget that technology is the true economy. That is why OLEA appeals to the collective memory in the history of mankind, where as early as 15 BC we have traces of genetic alterations in cereals, which led to the birth of added value in the exploitation of the land and gave rise to the concept of agriculture, a sort of value-added structure to a fractal production ecosystem. It is, in a synthetic way, the same thing that happens with the blockchain, a territory that is endowed with value through the creation of tokens. All these ingredients led to the production of this project.

It is true that I left behind more individual concepts related to personal data to appeal to something less individualistic. In recent interviews I keep repeating a phrase that perhaps explains this leap in my career: “In the era of fakes and empowered artificial intelligence, any personal story is possible. The challenge is to create collective stories that change us and influence us all. My work doesn’t talk about me in the first person, but about us.”

“In the era of fakes and empowered artificial intelligence, any personal story is possible. The challenge is to create collective stories that change us and influence us all.”

OLEA involves two very different technologies such as blockchain and genetic engineering, which however are both linked to the concept of registration and storage. What do these technologies bring to your work and how are they essential to the concept of this project?

Indeed, OLEA is a work that belongs to two intertwined worlds and that is what I intend to show when I exhibit it. Working with genetic code, which is still in a very primitive phase, requires a very interesting process of information synthesis, just as it happened back when we stored information on floppy discs.

This is also the case with the information stored “on-chain” in the blockchain, which also has its storage limitations, which is another interesting and common feature in the current state of these two technologies. Both are special to me for the way in which they leave their mark in their different materialities, as well as for their invitation to have faith in the technology or the value they bring to the ecosystem to which they belong.

Blockchain is basically based on a chain of blocks that stores metadata that actually have little meaning if they are decontextualized. Moreover, when we look at those blocks all we see is the hash in the log and the wallets involved in that transaction. It is something visible but that actually gives us very little information. It is we the users who assign it a value and presume it is a valid asset that refers to an artistic work or token.

We must have the same faith when we see a material containing DNA with the same information that resides on the blockchain. Now, we see the material it refers to but we do not see the code (we could see the DNA at a microscopic level). This game of consciousness, respect and trust in relation to the artistic object seems conceptually very interesting to me. It is also similar to the playfulness we find in great works of art that have questioned our beliefs and allowed us to overcome established assumptions as to what a work of art is. I believe that, as a contemporary artist, I should bring what I can to this constant reframing of our expectations towards art and that is why all these notions come together in OLEA.

Solimán López, Celeste, 2022

What do you make of the irruption of the NFT market, its boom and bust? What has it meant for you in your work as an artist? What is your perception of NFTs and what future evolution do you see in them?

I see NFTs as something that was bound to come sooner or later. I imagined them when I founded the Harddiskmuseum in 2013 as a museum that houses unique files or in the File Genesis exhibition (2017) where unique files are generated in real time that are stored in marble stones equipped with a USB stick, or the CELESTE project from 2016, in which we generated tokens from the digital images obtained from different colors of different skies distributed around the world.

With this experience, I was ready to take on NFTs in a very natural way, including their market decline. A decline that, in fact, corresponds with all the hypes in the history of technology, sports and other disciplines.

In my work, NFTs are a practicality and a conceptual field of work. Accepting the blockchain as a fractal environment easily connectable with nature is a great evolution in technology, and to me it is a great milestone to have incorporated it into my work.

Let’s also remember that I was the first artist to sell an NFT at a contemporary art fair in Europe and possibly worldwide, since ARCO was the first post-pandemic fair to come to light. This sale renewed my confidence in a format that I still think is here to stay and that is becoming normalized and naturalized in its use, as it is a fair and necessary format for digital art.

I see the future of NFTs as being even more integrated with real objects (I myself am still working on this and in the process of patenting what I call biotokens) and above all we will stop talking about NFTs merely linked to art. This technology will be in our daily lives as soon as the capitalist and mass control systems loosen their grip and allow WEB3.0 to develop freely, including those belonging to the art world.

Solimán López, OLEA Space 03, 2023

NFTs have brought renewed attention to the use of blockchain in art projects, which already had a first boom in 2018. Regardless of its use for the registration of non-fungible tokens, what possibilities do you see in blockchain in the creation and commercialization of digital art?

Art has a history of occupation of spaces. This is made clear after modernity. Let’s remember the occupation of the streets by urban art, or of the internet by net artists or social media artists. Now the same is happening with blockchain, where we are witnessing an occupation of this technological medium as well. The possibilities are many, but let’s not forget that without a solid concept, in the era of the mechanization of tasks, robotics and artificial intelligence, the word Art with a capital “A” is easily refuted.

That is why I believe that we must continue to resignify this space of creation and provide it with powerful conceptual contents that generate thought and offer value. The possibilities of creation that I see with blockchain go through its own evolution as a medium and its insertion and conjugation with other technologies, including biotechnology, a place where I am currently very comfortable conceptually.

“Art is going through a very convulsive moment, trying to resist the cannons of a sustainable, dematerialized and conceptually advanced future.”

On the other hand, the possibilities of WEB3.0 and blockchain in the construction of spaces of thought and communities, has no historical comparison. This notion is very interesting and opens the door to a new concept of the artwork as a social ecosystem mediated by itself and not by museums or other cultural structures, including the self-management of sales and dissemination of the artworks, which is opening the door to other agents with its consequent mutations.

Undoubtedly, art is going through a very convulsive moment in its own foundations, finding great threats in the already traditional contemporaneity, which continues to defend its castle of post-industrial tangibility, trying to resist the cannons of a sustainable, dematerialized and conceptually advanced future.

Your work is closely linked to scientific research. How do you collaborate with teams of researchers and how do you conceive the role of art in relation to scientific dissemination?

I feel that real art has always been linked to science and its connections with scientific research and its other main actors. Let’s not forget examples such as the influence of the work of microbiologists James Watson and Francis Crick in the paintings of Salvador Dalí: Dalí was captivated by the discoveries published by the two scientists and did everything he could to get in touch with them. His interest in the findings about DNA led to the appearance in many of the artist’s paintings of the famous representation of the double helix (incidentally thanks to the photographs of the scientist Rosalind Franklin).

I believe that the role of art is established when the work is scientifically solid and the resignification of both researches is achieved for the benefit of a common one. It is at that moment where the culmination comes and a great excitement in which you feel that the pieces are conceptually fitting together. I also believe that art is a fundamental tool for the changes of our time and in this field we cannot leave behind the scientific discoveries that are conditioning our future.

“I feel that scientists are also artists in their own way and with their own intentions, so the relationship is always very fluid and of mutual learning.”

In 100% of the cases, I have had excellent responses and collaborations. I feel that scientists are also artists in their own way and with their own intentions, so the relationship is always very fluid and of mutual learning. Undoubtedly an extremely rich and mandatory field to continue making contemporary art.

Normally I start with a crazy idea by linking some strands that a priori were disconnected. At that moment my scientific research begins and I start looking for papers, publications and records of what interests me and alludes technically to the work that is already in process. This is where I start to identify some key players, both companies and individuals, and I start to communicate with them, explaining my objectives and joint opportunities. At this point, a very rich production process is born, in which conversation is fundamental and sharing is evolving.

Your most recent project, Manifesto Terricola, combines the theme of memory with biotechnology and climate change, in what can be interpreted as an increasingly clear transition from the individual to natural systems and ultimately the relationship between humanity and the planet. What new aspects does this project bring to your work and what thematic avenues do you plan to develop in the future?

Manifesto Terricola is perhaps the most social project I have ever developed. Along with the Harddiskmuseum, it is a kind of project that you know will accompany you for a long time and that will be revised and even evolved or reinterpreted in the future (if we have any left). It brings me perhaps the possibility to engage with a more global community and not just the art niche, and of course it offers a pragmatic solution to the storage of our digital legacy through DNA and glaciers.

When you travel to a place like the Arctic you ask yourself questions that are already implicit in the manifesto, such as the habitability of the Earth for humans in the near future and the drift of the human species because of this issue and because of technology itself. In this sense, there is a mental doppler effect that forces you to want to go further and further with your work.

That is why the limits of my work are now also focused on space missions for example and to continue exploring those conceptual missives that the natural and the digital can send each other through the action of art and biotechnology until they live in harmony.

This line of work will continue to be very present, because as I mentioned before, these are places where I feel very comfortable since I believe that biotechnology will change the way in which human beings will relate to an unstable environment in changing conditions. Art can only survive from this position and from the understanding that we are Terran artists.