Pau Waelder

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Refik Anadol (b. 1985, Istanbul, Türkiye) is a media artist and lecturer, whose meteoric career has taken him from creating video mappings on building façades in several European cities, to being one of the first artists in residence at Google’s Artists and Machine Intelligence Program, the founder and director of Refik Anadol Studio RAS LAB in Los Angeles, a lecturer for UCLA’s Department of Design Media Arts, and a successful artist with global recognition in the contemporary art world. In just 15 years, Anadol has amassed numerous awards and presented his site-specific audio/visual performances at iconic museums and events such as the 17th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Walt Disney Concert Hall, Centre Pompidou, Daejeon Museum of Art, Art Basel, Ars Electronica Festival, and the Istanbul Design Biennial, among many others.

He works with a large team of designers, architects, data scientists, and researchers from 10 different countries and has partnered with teams at Microsoft, Google, Nvidia, Intel, IBM, Panasonic, JPL/NASA, Siemens, Epson, MIT, Harvard, UCLA, Stanford University, and UCSF, to apply the most innovative technologies to his body of work. He is represented by bitforms gallery in New York.

bitforms is participating in the Art SG art fair in Singapore from 12 to 15 January 2023, presenting a selection of generative artworks by Refik Anadol. Niio supports the exhibition as technical partner, in collaboration with SAMSUNG, and is proud to present the artcast Refik Anadol: Pacific Ocean, which features excerpts from three pieces by the Turkish artist. The following article offers a brief introduction to the main aspects of Refik’s work.

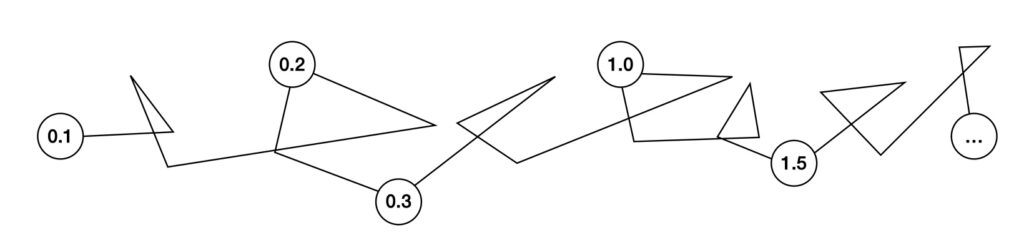

Image sold on Feral File as NFT. 100 editions, 1 AP

Building a latent space

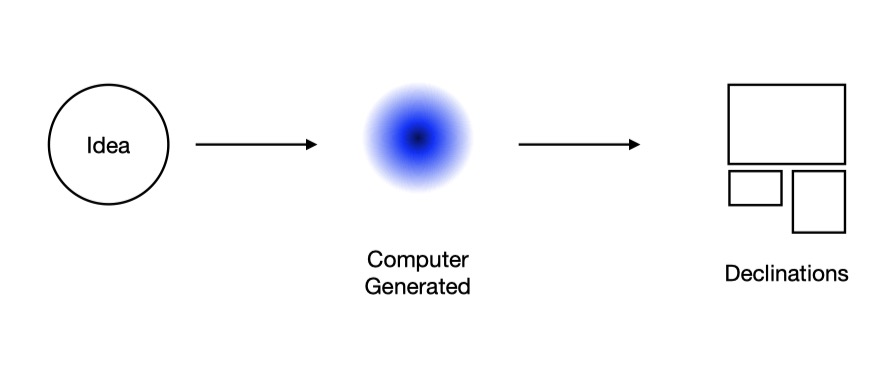

A trailblazing artist in the field of art and artificial intelligence, Refik Anadol uses large amounts of data and machine learning techniques to create his generative artworks and site-specific installations. His creative process often implies the creation of a data set from an archive of images, sounds, and documents or from measurements taken by sensors, radars, and other devices. The data set feeds a series of machine learning processes that generate an endless succession of audio-visual compositions, which can fill a large screen, a whole room, or the façade of a building.

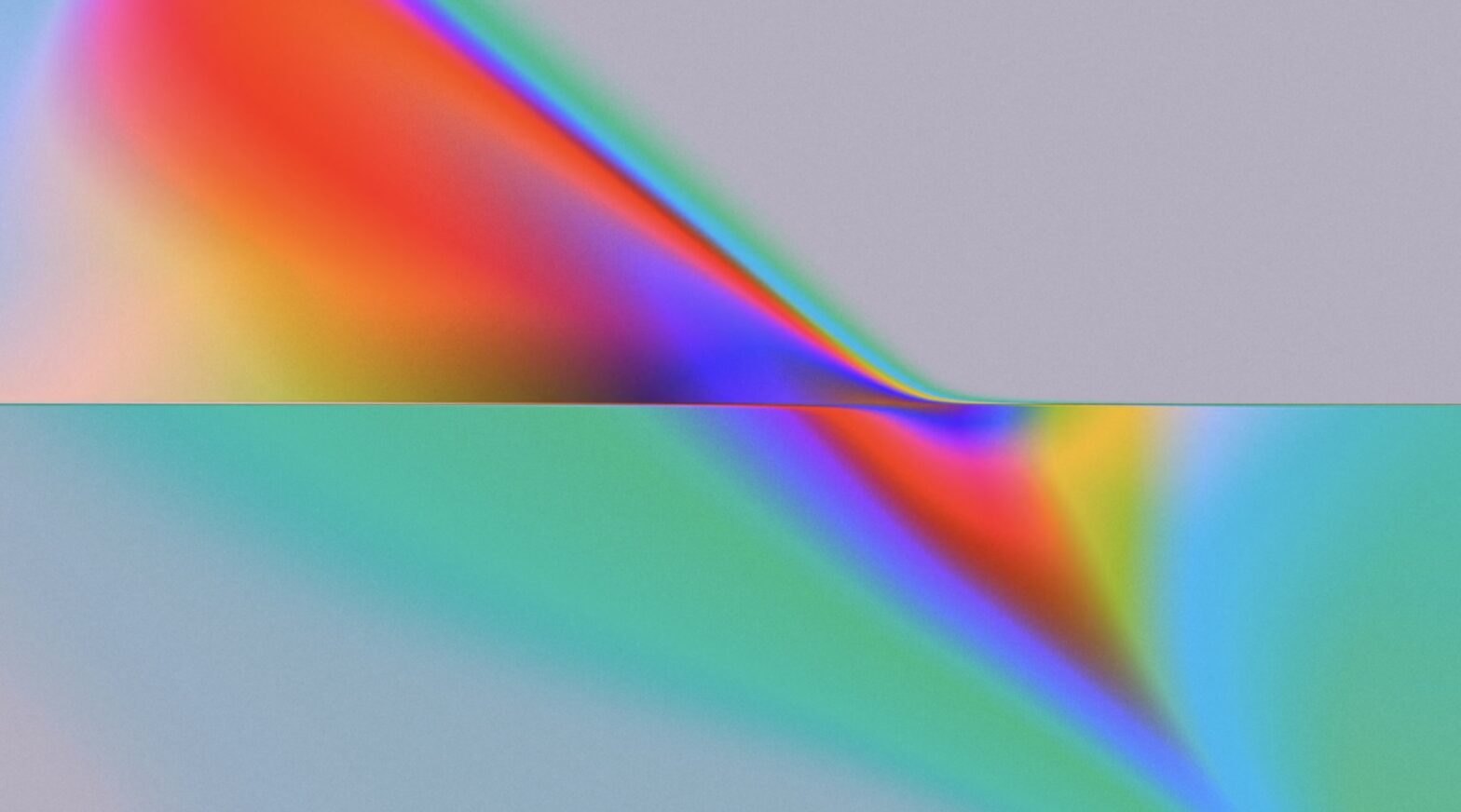

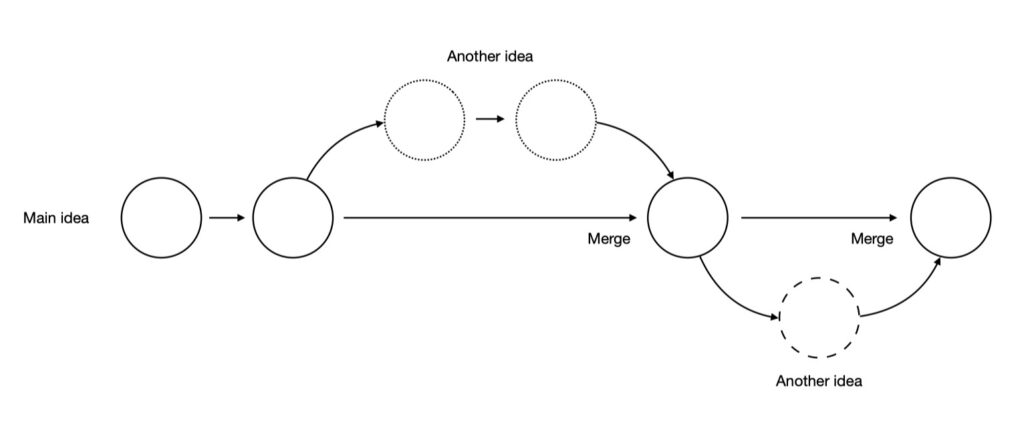

At the heart of the machine learning models that transform the original data into something else lies what is called a “latent space,” in which clusters of items are formed from similarities between them, which give rise to a set of variables. The latent space is therefore a space of possibilities, somewhat unpredictable, that contributes to shaping the final outcome. In Refik’s work, it is not only part of the machine learning model but also a concept that helps understand his generative pieces and installations as spaces in which creation is constantly exploring its latent qualities. Spaces in which the artwork is never finished.

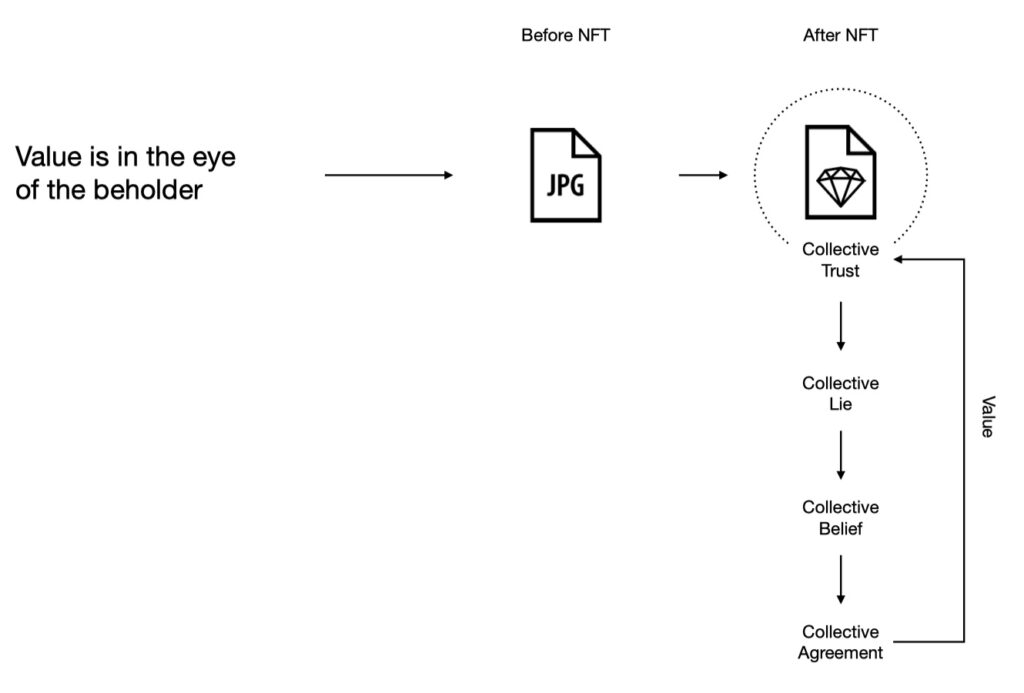

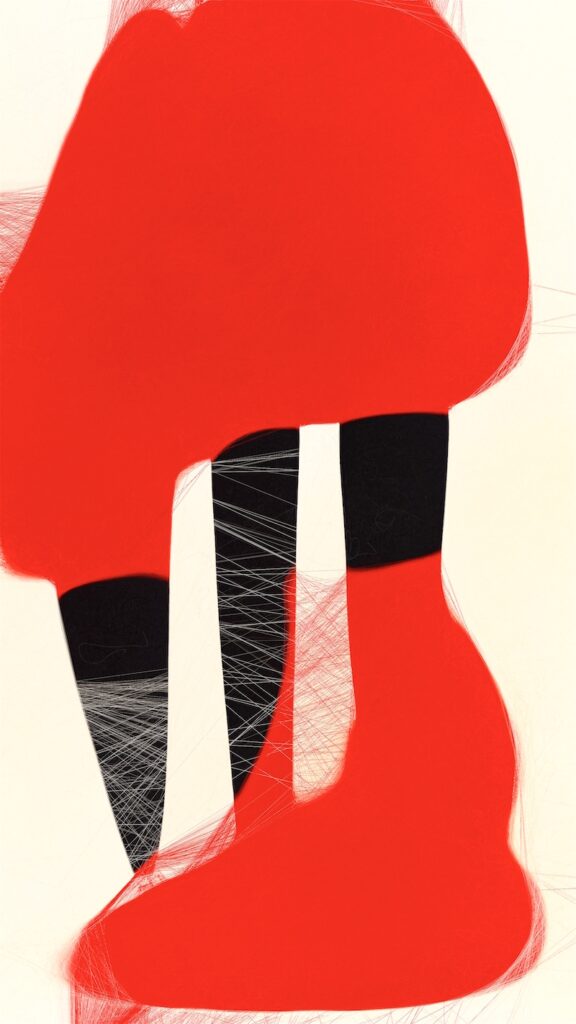

His recent installation at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Unsupervised: Machine Hallucinations MoMA (2022), clearly exemplifies the conception of the artwork as a latent space. Using the public metadata of The Museum of Modern Art’s collection, which comprises more than 130,000 pieces including paintings, drawings, photographs, and video games, the artist and his studio created a series of artworks that result from the interpretation of this data by means of a machine learning algorithm. The initial series was sold as NFTs in the exhibition Unsupervised on the online platform Feral File, the project being further expanded into the generative artwork installed at MoMA’s lobby. Casey Reas, artist and co-founder of Feral File, aptly described the artwork in terms of its latency: “What I find really interesting about Refik’s project with MoMA’s dataset, with your collection, is that it speculates about possible images that could have been made, but that were never made before” [1]. The artwork can thus be seen as a space of possibilities, but also as a simulated environment that becomes particularly meaningful in the context of the building that houses it.

Casey Reas: “What I find really interesting about Refik’s project with MoMA’s dataset is that it speculates about possible images that could have been made, but that were never made before”

The room as Merzbau

Architecture, and more generally a real or simulated three-dimensional space as a container, are key elements of Refik’s work. Artworks such as WDCH Dreams (2018) or Seoul Haemong (2019) use the exterior surfaces of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and the Dongdaemun Design Plaza in Seoul as canvases, while Infinity Room (2015) and Pladis: Data Universe (2018) are conceived by the artist as “Temporary Immersive Environments.” The artist stresses this connection frequently in his interviews: “I’m interested in exploring the architectural domain as deeply as I can,” he has stated recently. “All my art works tend to have a physical connection to public space” [2]. However, the architectural space is not conceived in terms of static shapes and volumes, but as something fluid and malleable, a work in progress.

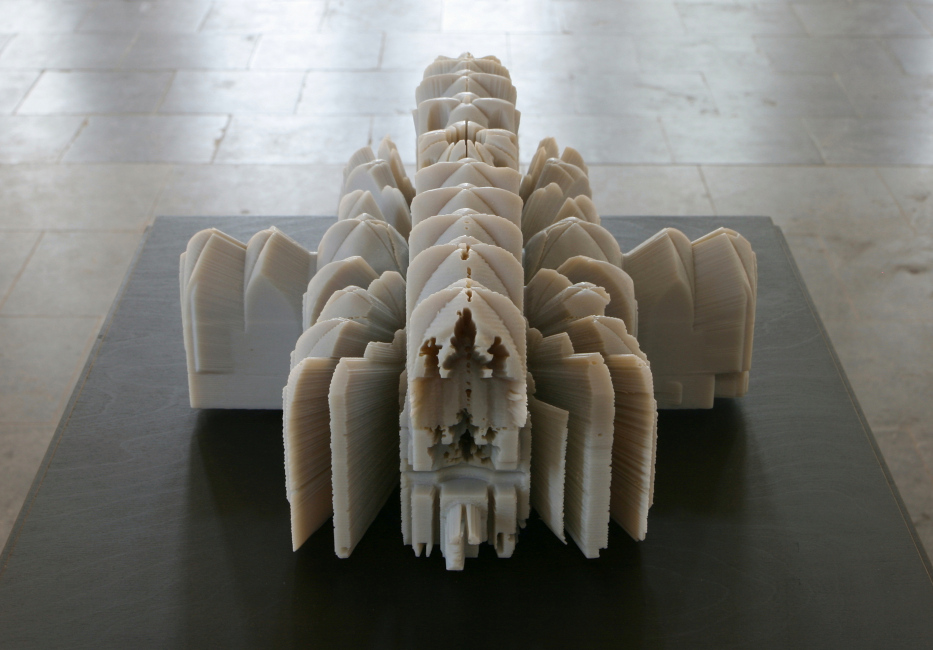

Kurt Schwitters’ celebrated Merzbau installations from the 1920s and 1930s come to mind as an illustrative example of Refik’s conception of space. Schwitters began to alter the space of his studio in Hannover by putting together small artworks, found objects, and debris into structures that he would glue and fix with plaster, building columns and shapes that protruded from the walls. The sculpture was never completed, the artist always kept adding elements and reshaping the space [3]. In a similar way, the space occupied by Refik’s artworks is permanently reshaped through a process that stems from an accumulation of found materials, data that loses its original shape and merges into something new. In the Temporary Immersive Environment series, he specifically seeks to immerse the viewer in a “non-physical world” that questions their perception of space and their own presence [4]. The room is expanded and multiplied through optical effects, with the aim of creating a viewing experience that goes beyond staring at a flat projection.

Refik Anadol: “I’m interested in exploring the architectural domain as deeply as I can. All my art works tend to have a physical connection to public space.”

This conception of space as integrated into a Gesamtkunstwerk, the “total work of art” that has been the aspiration of opera composers, architects and filmmakers, is not, however, the only connection with architecture in Refik’s work. Interestingly, while Schwitters sought to merge all of his artistic practice under one term (Merz), erasing distinctions between painting, sculpture, and architecture, Anadol describes some of his generative art works as “data paintings” and “data sculptures.” These references to classical formats speak of a different type of space, confined within the limits of a screen or a wall, which nevertheless intervenes in the surrounding space by means of a trompe-l’oeil effect that creates the impression of three-dimensional shapes pulsating beneath and beyond a solid, thick frame. Artworks such as Virtual depictions: San Francisco (2015), displayed on an L-shaped media wall inside the main lobby of the 350 Mission building in San Francisco, seek to create an imaginary space that stands out spectacularly, but at the same time embeds itself into the surrounding architecture. The connection between the artwork and its location, though, is not only expressed in terms of how the screen is placed on the wall, but also in the data that gives meaning to the fluid elements that inhabit the virtual space.

Data is not just a bunch of numbers

Coming back to the concept of latent space within machine learning models, it is important to remember that Refik Anadol’s artworks do not only have an aesthetic dimension, as colorful shapes in fluid transitions or enormous mosaics of distinct elements, but also a conceptual dimension, expressed by the data that feeds the whole process leading to the site-specific installations and performances. Speaking about his project Quantum Memories (2020), the artist states the importance of this data and the meaning it conveys:

“For me, data is not just a bunch of numbers. For me, data is actually a memory. From that perspective, I’m always looking for what kind of collective memory that we are holding as humanity, and how can we use these memories and turn them into a pigment or a sculpture that represents who we are as humanity.” [5]

Conceiving data as memory resonates with his ongoing work with all kinds of archives, from the 1,700,000 documents found in the SALT Research collections to the 587,763 image files, 1,880 video files, 1,483 metadata files, and 17,773 audio files in the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra’s digital archives. Every bit of information in these files has its own history and meaning, and has a certain association with another file, enabling the clusters and variables that will emerge in the latent space. The artworks may appear as abstract compositions or massive collages, but they are actually visual representations of underlying stories and invisible structures. As the artist puts it, they aim to “make visible the invisible world of data that surrounds us” [6]. This statement may lead to considering Refik’s work as a form of data visualization, but it goes well beyond this task, into what media theorist Lev Manovich has described as “represent[ing] the personal subjective experience of a person living in a data society […] including its fundamental new dimension of being «immersed in data»” [7].

Lev Manovich: “The real challenge of data art is how to represent the personal subjective experience of a person living in a data society.”

Some of Refik’s installations directly address this condition of being immersed in data by means of projections that surround the viewer with visualizations of the data collected from archives, or in real time from sensors and other sources, as in Latent Being (2019) or Future of the City (2020). Others present data that relates to environmental systems that we usually ignore but that have a profound impact on our planet, and therefore in our lives. This is the case of Pacific Ocean (2022), the series presented by bitforms at Art SG in Singapore and on Niio as an artcast featuring three video excerpts.

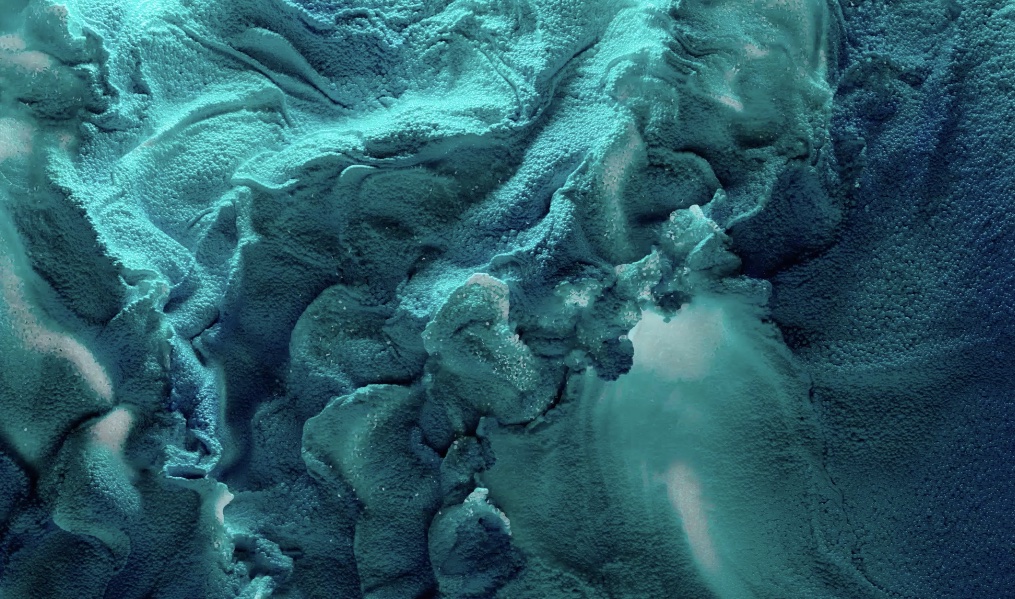

Collecting data from High Frequency Radars (HFR) located in the Pacific coast of the United States, the artist has created a series of visualizations of ocean currents that seems abstract and realistic at the same time: the ebbs and flows of granular elements in shades ranging from dark blue to emerald green clearly evoke the surface of a raging sea, but they are also somehow unreal, impossibly merging numerous currents from different directions in beautifully chaotic, and even violent, clashes. HFRs are used to measure ocean currents and understand their impact and response to climate processes. The data collected from networks of radars in coastal zones around the world is crucial to protect the marine ecosystem and predict changes that will affect life on our planet. Seen from this perspective, the artworks acquire a somewhat unsettling tone and inspire an awareness of the ecosystems that we so often ignore, putting into question our anthropocentric view of the world.

Refik Anadol. Pacific Ocean A, 2022

Machine dreaming

Anthropocentrism and our inability to understand the agency of non-human entities and systems around us are underlying subjects in most approaches to art created with artificial intelligence. The perennial question of whether it is the artist of the machine that creates the artwork is still debated after 60 years of algorithmic art, now reinforced by the spectacular achievements of machine learning models in producing realistic images and coherent texts. In Refik Anadol’s work, the use of artificially intelligent systems leads to two interesting aspects of artistic creation: the notions of control and authorship.

Terms like “machine learning,” “supervised learning,” “reinforcement learning,” and “training model” speak of the intention to use artificial intelligence as a tool to obtain predictable results, in which the machine is meant to produce a specific output. This perception of the machine as a mere instrument, fully controlled by a human, contradicts the way artists have used generative algorithms and AI systems to create their artworks. Nowadays, artists working with artificial intelligence understand machine learning as a way of exploring post-anthropocentric creativity, therefore using AI to reach beyond the confines of human imagination and let the machine bring in the unexpected, the incongruous, the unsettling, and even the impossible. In Refik’s work this approach is made clear in the use of machine learning models to create “dreams” and “hallucinations.” He has described AI as “a thinking brush, a brush that can think, that can remember, and that can dream.” This statement implies an interesting balance between letting the system loose and keeping it under control. In Archive Dreaming (2017), the installation is allowed to “dream” when a viewer is not interacting with it, so that this state is interrupted when a human takes control. In other installations, such as Machine Hallucination (2019), the system can create its own associations and reimaginings of the contents of a very precise dataset, so that its “unconscious” is nevertheless under a certain level of control.

Refik Anadol: “the most important thing for me is creating a thinking brush, a brush that can think, that can remember, and that can dream.”

The question of authorship stems from the perceived control over the final output: if the artist had no control over it, is he the author of the artwork? Interestingly, while the Dadaists and Surrealists already integrated randomness into their artistic practices and many other artists have incorporated unpredictable processes or external agents into their work, authorship tends to be more fiercely contested when a computer is involved. Refik Anadol’s authorship is nevertheless palpable in the aesthetic and conceptual foundations of his work, which remain consistent throughout his career despite considering himself part of a large team of experts and working with increasingly complex AI technologies. He conceives the process as a collaboration, both when dealing with software and hardware and when teaming up with designers, coders, and researchers to develop a project. There are, however, crucial moments when decisions are made, and these are the moments when the artist states his authorship:

“There’s a collaboration between machine and human. With the same data, we can generate infinite versions of the same sculpture, but choosing this moment, and creating this moment in time and space, is the moment of creation.” [8]

Out of infinite possibilities, making a choice that determines the next step in the process and shapes the final output is a prerogative of the artist, who is finally the author of the artwork that emerges from a latent space.

Notes

[1] Refik Anadol, Casey Reas, Michelle Kuo, and Paola Antonelli. Modern Dream: How Refik Anadol Is Using Machine Learning and NFTs to Interpret MoMA’s Collection. MoMA | Magazine, November 15, 2021.

[2] Dorian Batycka. Digital Art Star Refik Anadol’s First Supporters Were in the Tech World. All of a Sudden, His Work Has Become White-Hot at Auction, Too. Artnet, May 18, 2022.

[3] Gwendolen Webster. Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau. A dissertation presented to the Open University, Milton Keynes, 2007.

[4] Refik Anadol. Liminal Room. Refik Anadol Studio, November 19, 2015.

[5] Claudia Pelosi. Machine intelligence as a narrative tool in experiential art – Interview with Refik Anadol. Designwanted, December 19, 2020.

[6] Refik Anadol. Virtual Depictions: San Francisco. Refik Anadol Studio, October 1, 2015.

[7] Lev Manovich. Data Visualization as New Abstraction and Anti-Sublime. Manovich.net, 2002.

[8] Refik Anadol, Casey Reas, Michelle Kuo, and Paola Antonelli. Modern Dream. op.cit.