Interview by Pau Waelder & Roxanne Vardi

Alexandra Crouwers is a visual artist working in the digital realm, and currently a doctoral artistic researcher in animation at KU Leuven/LUCA School of Arts, Brussels. She lives and works in Antwerp, Belgium. Her works can be described as collages, assemblages or dioramas. Crouwers’ animation and images are constructed with 3D software and post production, and bring attention to the balance between landscape and architecture, silence and sound, materiality and immateriality, technology and a broad sense of art history.

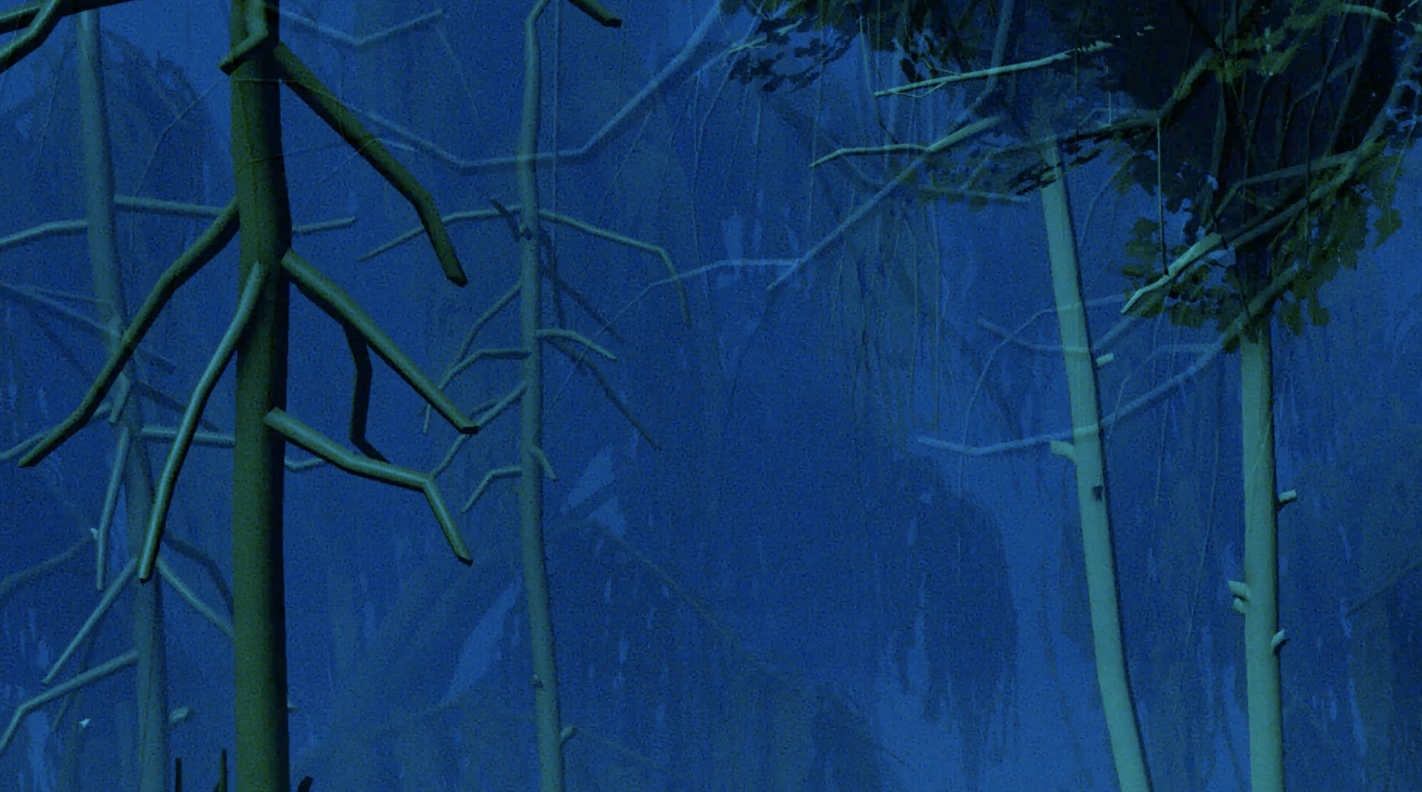

Diorama. The Plot: a day/night sequence, (2021) is featured in our recent artcast Anticlimactic, a selection of works from the eco-friendly NFT art community a\terHEN. The video work, based on a photogrammetric model of three tree stumps now called ‘The Plot,’ is part of Crouwers’ investigation of ways to deal with eco-anxiety and ecological grief.

Before discussing your artwork The Plot, can you tell us about the appeal of the unreal, and what brought you to research the concept of the diorama, which has become intertwined in your artistic practice?

I only realized that a lot of my work was, in fact, part of this whole concept of the diorama around five or six years ago. The field of special effects and visual illusions, and this sort of idea of simulated nature, simulated scenes, simulated wilderness has been lingering in my work for quite a long time. I think it’s also a part of where I grew up, in the Dutch countryside in the south. Since then I have been living in cities for most of my life. But as they say, you can take the girl out of the countryside, but you cannot take the countryside out of the girl. I noticed that I often start working by building a view, which I am lacking in the city. So there is a kind of innate longing for landscapes that are not there. This is connected to the idea of escapism; to escape from where you are at. The word nature has become very problematic: what we refer to as nature is quickly deteriorating in all kinds of senses. To me, simulating this idea of wilderness is like a twisted sense of digital nature, of purpose preservation. It is a way to deal with the idea of loss. Those are the things that connect to the idea of the diorama as a way to preserve something. The diorama is twofold: It’s the visual illusion that transports you (the immersion of a scene) and it’s the habitat.

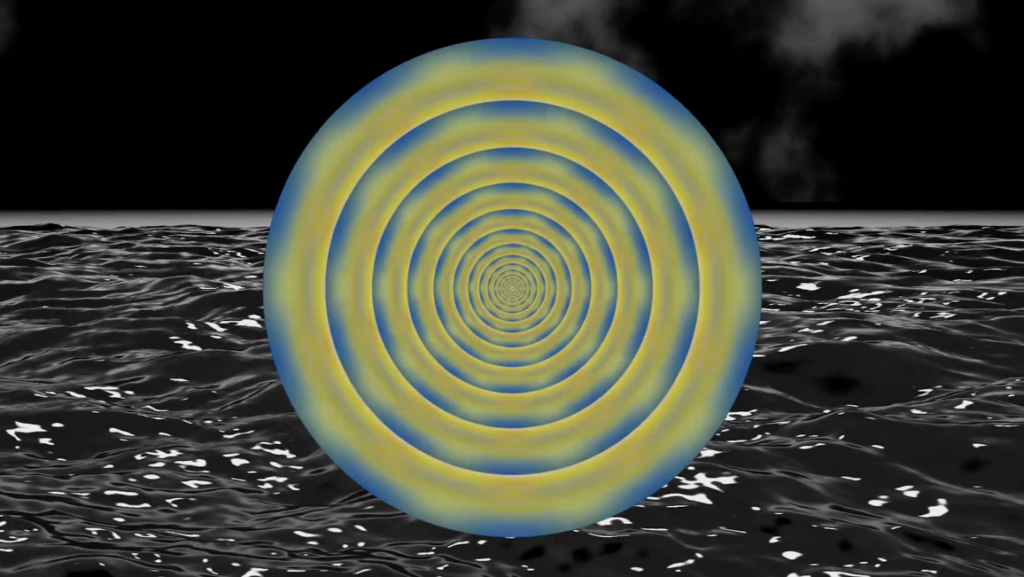

In a sense, I have a very desperate practice as I want to preserve things that cannot be preserved. I want to go back in time to prehistory and the origins of image making. Decorated caves, such as the very beautifully preserved Dordogne, are also immersive spaces. It’s a multimedia installation that uses light and sound where a lot of the paintings almost seem to move with the surface. Thus, there is this idea of visual illusions also being a part of our whole history with image and the experience of image. Transporting pieces of my grandfather’s forest or plot to the digital X, Y, and Z axis by using photogrammetric models is, in a sense, a ritualistic way of transporting something from one realm to another. But visually, it’s very interesting, because from a distance, I am carrying out a sort of healing as a performative action, which I am interested in further exploring. The idea that technology is something very rational is absolutely not true. It’s like the illusion that people are rational or that they grow up. They never do. So I read and own some fantastic literature on that, specifically about the relationship between technology and for instance, spiritualism, like radio waves for example. These things are also connected into this fantasy science fiction world, which gives us really a lot of freedom to stretch a practice.

“The word nature has become very problematic: what we refer to as nature is quickly deteriorating in all kinds of senses. In a sense, I have a very desperate practice as I want to preserve things that cannot be preserved.”

You discussed the connection with prehistoric culture which gave us the first multimedia environment. In works such as The White Hide, (2012), Last Voices, (2017), and Millenial.spike, (2018) one can clearly see your interest in Neolithic culture. You also worked on two emoji proposals which are fantastic. Can you elaborate on how you work around those references and what they mean to you?

I think that there are some practical reasons for this. For instance, if you want to say something about the way that our brains work you have to go back into history, because otherwise you would not understand it. Going back into this, we realize that we are all one. The fact that those hand stencil cave paintings are found all over the globe is just amazing. It’s so fantastic that I really don’t understand why the emoji proposal was declined by the Unicode Consortium. The hand stencil is the first emoji, really. I think that one of the most amazing things that we have is this ability for making up stuff. The wider field of the arts is the habitat for making stuff up. The whole idea of fiction being the base of everything we do really is just quite amazing. On a cinematic level, I have always been incredibly influenced by science fiction films and the slowness of Stanley Kubrick. I learned all this 3d software by myself, and very quickly was simulating what big studios were doing. I have moved away from that a bit because it’s very time consuming, and also not always feasible. I like the fact that the visual language of the digital image has also exploded, and one can more or less use so many more types of digital imagery such as, for instance, the photogrammetric models.

Diving a bit deeper into The Plot, you said that it relates to your family history. At first glance, the work brings up notions of nature and the idea of eco anxiety. By reading this aspect of your family history one realizes that it is more personal, sentimental and experiential than might appear at first.

I am not entirely sure if that was the meaning. In hindsight I have been suffering from eco anxiety for 20 years. When I graduated from art school, we had to write a paper and I wrote a nonlinear story. It was written in separate sheets of paper, so the reader could decide in which order to read them. Everything that I am doing now is in there. It is, in essence, a science fiction piece. There are even aliens mentioned in there. But there is also a deep concern already about the temperature rising. Back then, people were already saying things like ‘oh, this is an unusually warm January’ or ‘oh, spring is coming’. But, I was already really very worried. In the paper that I wrote, I already questioned why people are so happy about this. In hindsight, I am not entirely sure where that exactly came from. I had been reading about it at the time, and I always watched a lot of disaster movies. Just as a sideline, there is research that proves that people who watch a lot of horror and disaster movies are much better equipped to deal with things like a pandemic. So, maybe it was because of all the disaster movies that I had been seeing as a child growing up near the German border. This eco anxiety completely predates even the idea of this forest being a part of my work. The first time I saw it after it was cleared I realized that it wasn’t even a forest, but a small monoculture plantation. Even though my whole family still refers to it as the little forest.

There is a sentimental reason that my mom has it now, and a very sentimental reason that my grandfather bought it in the first place. In the 1950s and 60s my grandfather was a farmer, and his family was forced to trade lands to make bigger plots. Moreover, the state was building a highway. Because my grandfather lost so much land that was originally built from family bits and pieces and patches here and there, which was the custom before the 1950s, he wanted to buy something back that actually related to his family history.

So by making this diorama you are in a way recovering the family plot. I was wondering whether these three trunks were left there or whether this is something that you asked for?

When I came there I saw the devastation, but there were these very tall birch trees and some pine trees still standing. Because the forest used to be so dense they just grew really tall and thin. Every time there is a storm more trees just blow over, which makes it even more dramatic. I don’t know if the forester had an aesthetic motivation to do that. But they were just there like a perfect monument. Moreover, the distance between the tree trunks gives them their own personality, and especially the tallest one, which is very much in decay at the moment. Usually, when I create my works I use the computer. I take an idea, and put it in a computer, but in this case, the plot actually dictates the work. In a dynamic sense, you need not interfere but just look at it.

You once wrote that a diorama usually has a distinct educational purpose as it tries to show us something that we otherwise would not be able to see. Even though we know that climate change is worsening we retreat to digital spaces as escapism. How much of that educational quality or bringing into sight is there in working with the dioramas?

As I am doing my PhD in art, it’s art and not science. The models are also used, for instance, in archaeological sites as documentation. It’s just that they happen to be very artistic or that I make them artistic. So it is in that sense documentation, but then I turn it into art. So they are educational when I talk about them. I regularly get invited to talk to students about ecology and activism and art and how to connect the art and the digital. So in that sense they also function as illustrations of how these things all come together.

In your work there is also a connection with the Romantic idea of the landscape and the ruin. Was this a conscious decision?

It’s interesting because the landscape in the Romantic era was meant to be so impressive that one would feel very small. In that sense, the romantic landscape works really well as a reference to the sublime. That also helps communicate the landscape, which itself is already a complex concept, because it is actually a cultural construct. I barely like to situate humans in my work. There is already too much centered on us. What we need is to experience the outside.

Given that this work was originally presented at a\terHEN, could you further elaborate on what drove you to exhibit your work on this platform and on your experience with NFTs in general?

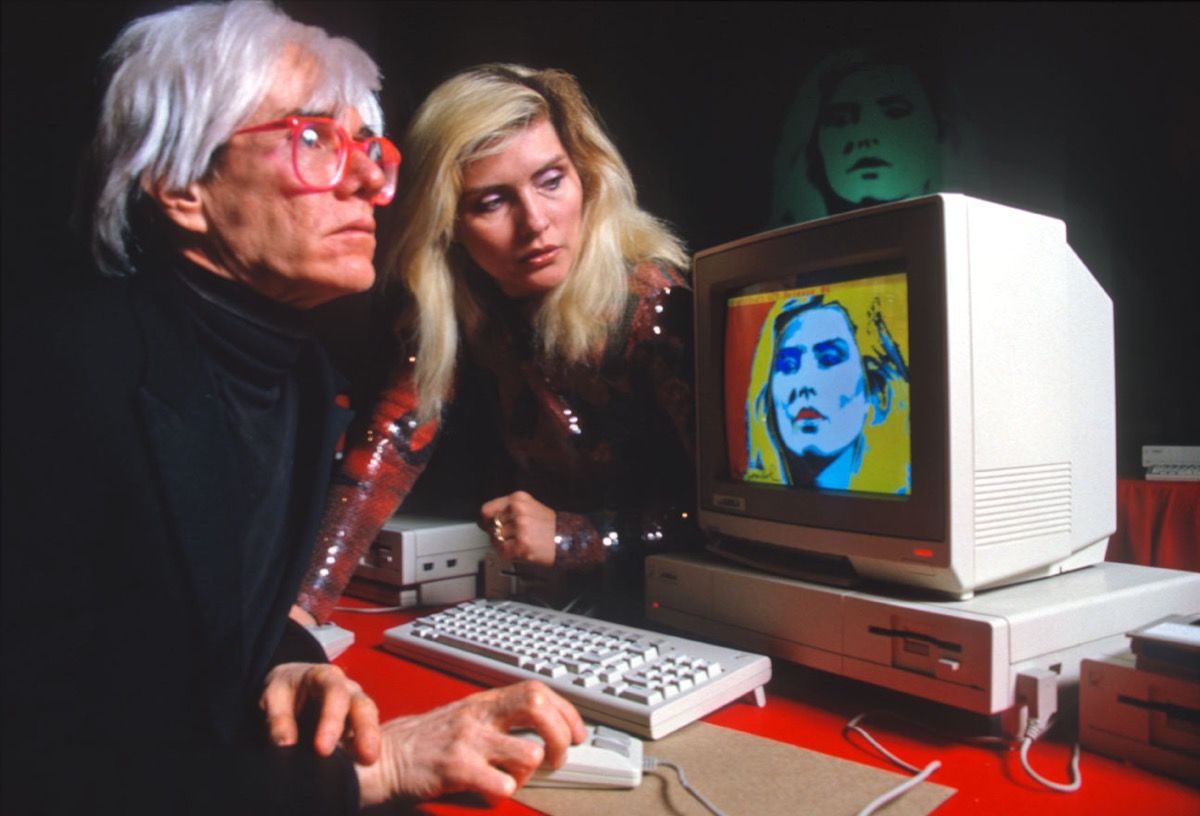

When the NFT entered my field of view, I didn’t really know much more than most people who were reading a newspaper. So I think I only consciously registered the idea when Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days was sold. I was also not really sure what it had to do with my work. But at the time, I was giving a class to students in Brussels titled Digital Dimensions, and I thought to myself ‘well, this is a digital dimension, this is quite new’. So I started reading about it, and I read for about two weeks straight. Around the same time I also reunited with Kelly Richardson. We have become each other’s mirrors to bounce ideas off each other. I was also very happy to have found a place without all the clutter around it. There is a gap in people’s knowledge of the digital arts which can be a bit frustrating and that is something that NFTs might help to explain.