Pau Waelder

This interview is part of a series dedicated to the artists whose works have been selected at the SMTH + Niio Open Call for Art Students. The jury been selected at the SMTH + Niio Open Call for Art Students. The jury members Valentina Peri, curator, Wolf Lieser, founder of DAM Projects/ DAM Museum, and Solimán López, new media artist, chose 5 artworks that are being displayed on more than 60 screens in public spaces, courtesy of Led&Go.

Cosette Reyes is a Mexican designer, artist, anthropologist, and biochemical engineer. Over the last few years, she has participated in international research projects in the fields of mental health, human evolution, and cognition. This extensive research has inspired a deep exploration into the phenomenon of the mind and its corporeal expressions through design and art. Currently residing in Valencia, Spain, Reyes is in the third year of a Degree in Graphic Design and Digital Media at LABA Valencia, School of Art, Design & New Media. In addition to academic pursuits, she leads several creative and community-building projects.

Since 2022, Reyes has collaborated with House of Chappaz, a prominent contemporary art gallery in Spain, contributing her expertise in motion graphics, 3D, and video art. The choice of the nickname “Ammoniite” reflects a fascination with its connection to science, art, and mystery. The fossilized figure, with its ideal aesthetic proportions, aligns with her main interests. The added “i” in the name symbolizes a commitment to interdiscipline and innovation in professional practice.

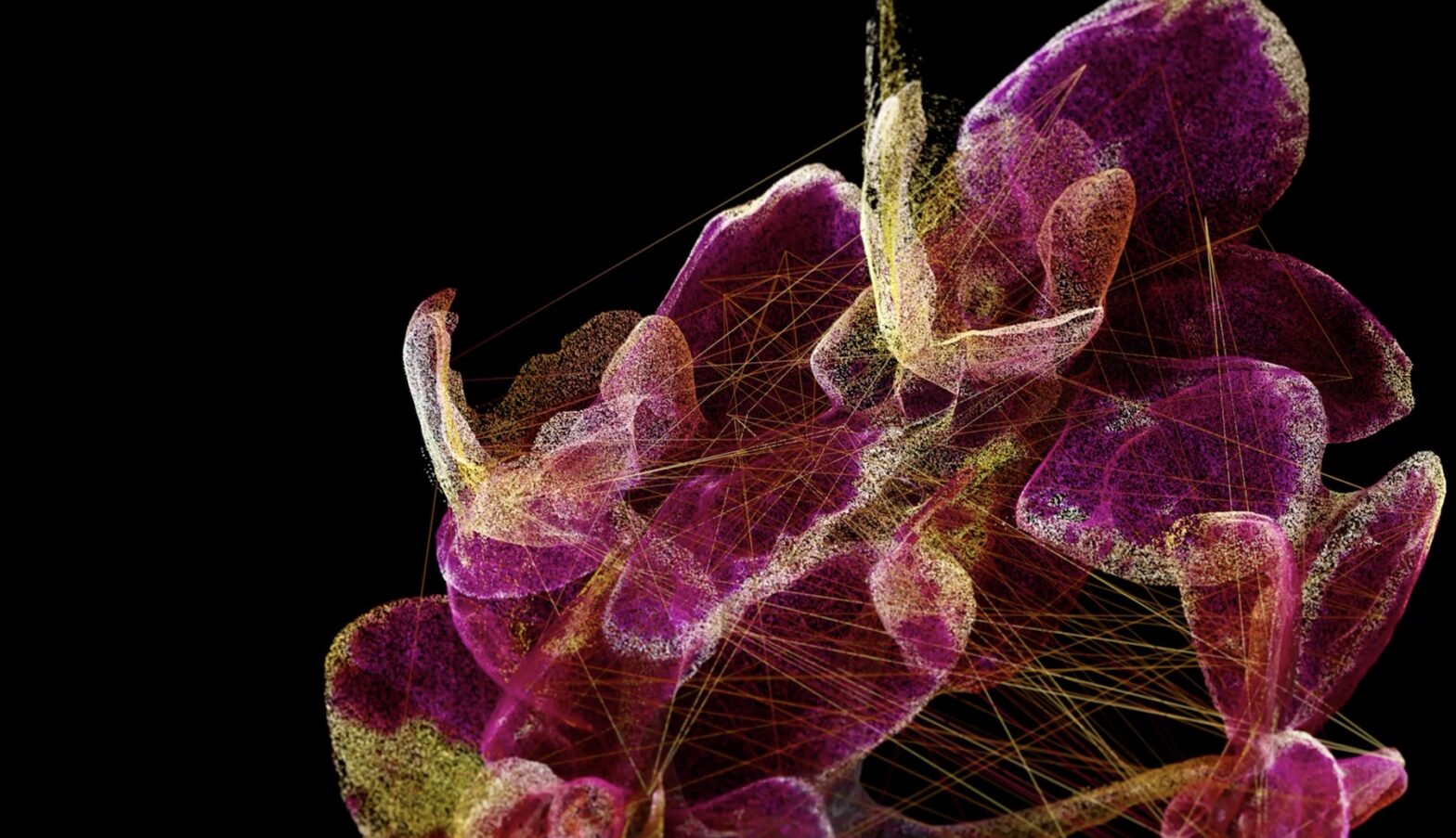

Cosette Reyes. Instante, 2024

Your work focuses on the exploration of the mind, with a direct application to human-machine interaction research in interface design. Can you tell me about these two facets of your work, how they relate to each other?

I seek to articulate the whole corporeal part of the human mind, with its behavior and the relationship it has with the new media. I find it especially interesting to explore how the human being leaves its mark on new technologies and this feeds all the systems that will later interact with the humans of the future.

“We have, as designers and artists, the great responsibility to show the options that are available, instead of imposing a unique vision or use.”

As a designer, I think we are at a key point where we are not using all the knowledge we have about human behavior. We have gone from using color psychology and marketing techniques to having a wealth of information about users’ habits, which we can transfer to the users themselves. This opens up a wide range of possibilities, paths, ways of interacting with technology and allows us to go back to introspection and get to know ourselves through our own body and the environment, whether digital or tangible. We have, as designers and artists, the great responsibility to show the options that are available, instead of imposing a unique vision or use. Something that characterizes us as humans is to be curious and to have the possibility to choose. Through design we provide solutions, challenges that we solve with our creativity and the answer to these challenges are creative solutions that provide many options for our user or viewer: it is not about guiding them, or giving them a guideline towards one choice or another, but letting them know that they have all these options, always within an ethical framework, within the legal framework and the context in which we find ourselves and above all with the exercise of our own rights and respect for the rights of others.

You are studying in the Graphic Design Degree at LABA Valencia. How has your experience in this degree been, what does it contribute to your professional and artistic development?

In LABA Valencia I have developed a lot of technical skills, I have acquired a lot of basic knowledge and I have learned a lot of software, especially new technologies. But what I have valued most about LABA in terms of knowledge in the field of design and the creative sector is that we have contact with working professionals. These professionals make us very aware of what the sector is like, what the market is like, and how they have had this approach with a client, whether it is the Generalitat Valenciana, or the education sector, or even in associations where the clients are themselves. In LABA Valencia, the human aspect stands out. The teachers are very up to date with their syllabus, with all the educational proposals, but they always put a lot of emphasis on the human side, on the tangible and physical side, and on working with real cases, with a global perspective but also, so to say, with the feet on the ground. In the Design Thinking process they put a lot of emphasis on empathy. Empathy has greatly enriched all the knowledge I had and I have been able to articulate it now with design, which has led me to observe human behavior and people in a more global way. But always with that sense that connects and that is incipient to us: being creative, being curious, and above all something very important that is collaborative. That is what LABA Valencia has given me the most: the experience of collaborating.

It has also helped me a lot to meet people who are starting out in the sector, and to share the day-to-day with my colleagues and peers. That is very enriching. Valencia is a city that inspires, a quiet, green city, which is closely linked to design: it has quite an important history in terms of design. All the designers who are now active have had this contact, not only with the community but also at a national level. In the field of design in Valencia I have seen that there is always a discourse and a social motive. They look not only at vulnerable sectors but at things that matter to the community. They are always at the forefront, not only in terms of graphics but also in social movements. It is one of the cities with the highest quality of life.

“What I have valued most about LABA in terms of knowledge in the field of design and the creative sector is that we have contact with working professionals.”

You collaborate since 2022 with House of Chappaz, from this perspective, how do you see the art market today in relation to digital media? What possibilities do you see for artists?

I have had the opportunity to collaborate for about a year with Ismael Chappaz’s gallery, which is a reference gallery in Spain. The gallery is very supportive of design, but above all conscious design, design with a reason. As for the position of digital artists in the market, I think it has evolved a little slower than all the new media and everything digital. Acceptance has always been complicated, because especially after the pandemic we have gone more towards contact, towards everything tangible. But currently and in the last few months I have seen that this impulse to go towards digital and for artists to express themselves in these non-tangible media has been much more supported. I have also noticed that when projects flow better is when there is another physical, tangible and “classic” part, so to speak. In interactive exhibitions, where there is participation of the body, is where I see more possibilities for digital artists.

Your work was selected in the previous edition of the SMTH university call. What was your experience then? How do you see the current collaboration with Niio and the options it brings to artists?

I found it very interesting to bring this art to all kinds of audiences, and not to limit it to museums or spaces where a public that is already interested will experience it. It is important that this happens after the pandemic, because we were quite disconnected in the sense of the body and the tangible, but very connected in a more ethereal sense. I don’t consider that to have been a bad thing, but rather that we’ve been given the opportunity to see how we can be in both environments and have this more hybrid essence. That you go to a physical space of leisure, recreation, being more connected to yourself and seeing the works that speak to your own body, I think that was a very important point to reconnect with all of that. It can be for all audiences a point of inspiration, and I have also seen it in the second call: the artists have brought a much more introspective and more conscious discourse in terms of new media, and also in terms of the body. It’s revealing that most of us have touched the collective: that’s a very interesting process in which you discover yourself as a person and then you see what’s around you and how you can collaborate.

“I found it very interesting to bring this art to all kinds of audiences, and not to limit it to museums or spaces where a public that is already interested will experience it.”

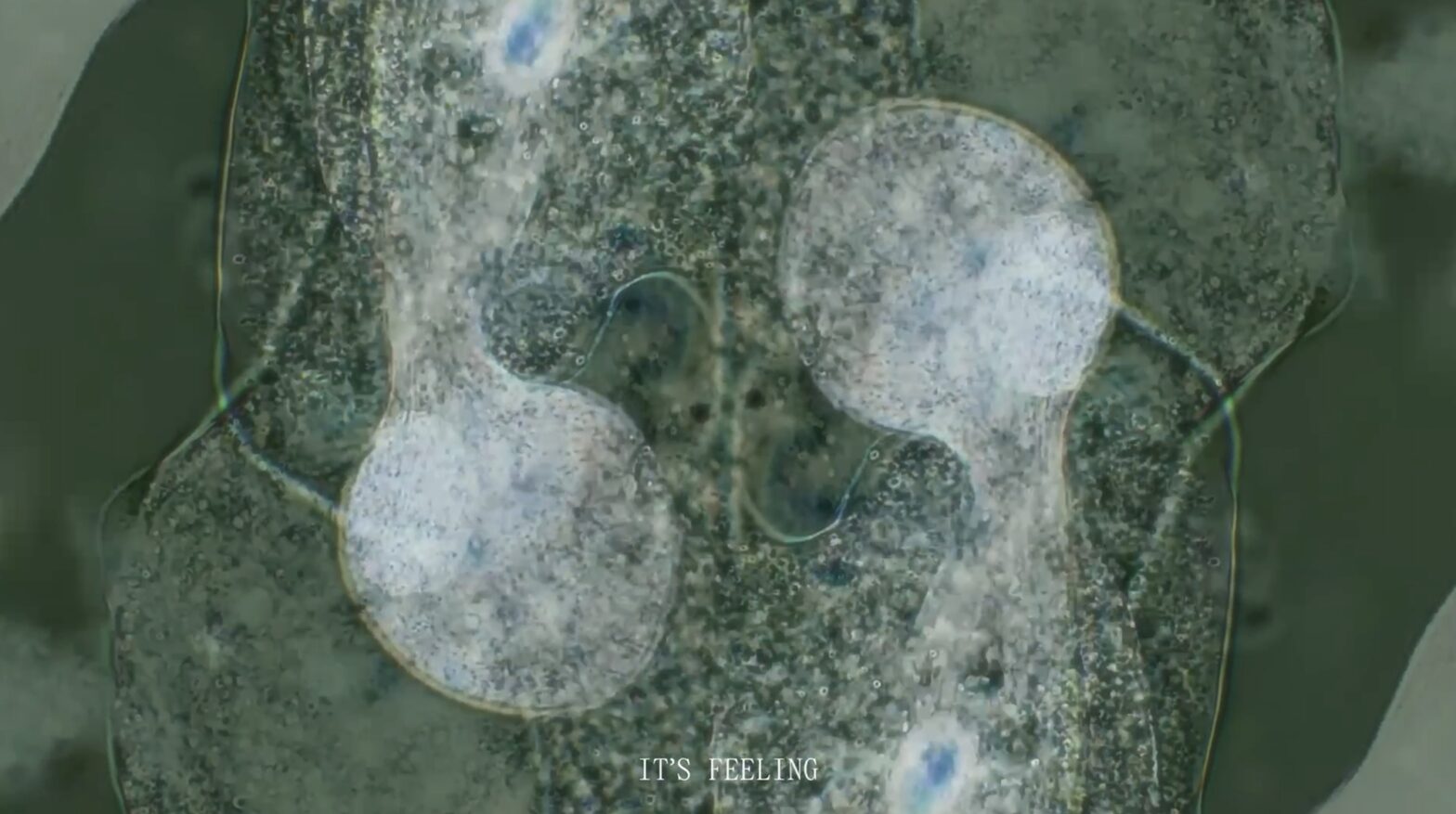

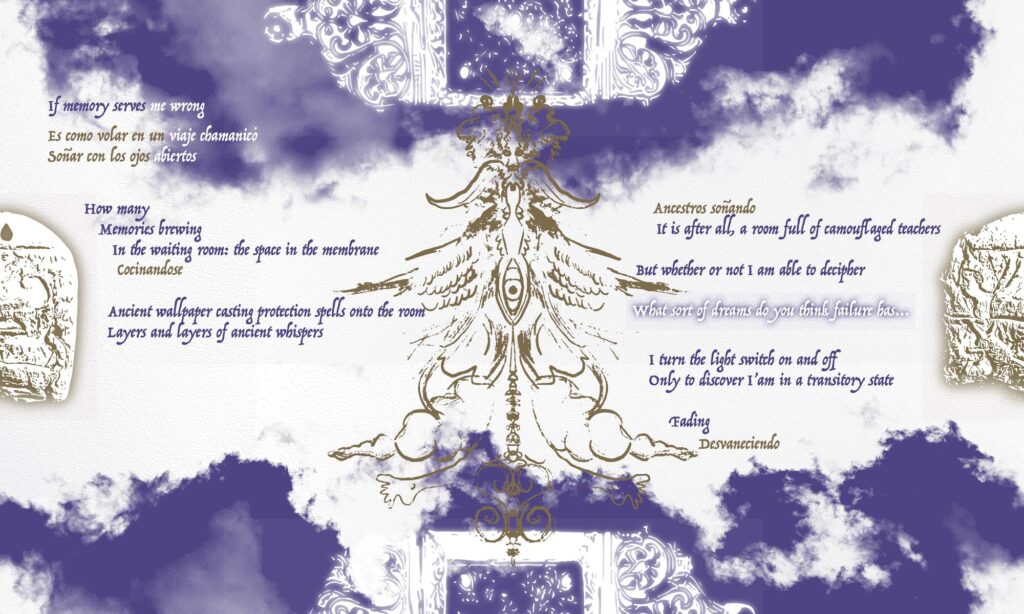

Tell us about Instante: you have worked with Artificial Intelligence programs to generate the dreamlike images that populate this video. How does this piece fit in with your work and your fascination with surrealism? What has it been like to work with AI?

In this work I had thought of doing something else more inclined towards video art, much more about the body but with touches of reverie, capturing physical spaces in which we find ourselves safe, but that we can no longer find. Regarding working with AI, although it seems that these systems are automated and that we only have to give them a few instructions so that everything builds itself, it turns out that there is a kind of dialogue: when I started, I had something very concrete in mind, but when after interacting with these models of artificial intelligence I realized that it wasn’t two or three clicks. So I decided to take up the idea of how our mind doesn’t always reflect what’s going on through our own corporeality. So I gave myself the task of looking for many more references, to give a twist to the idea I had, because it was going the other way and I found it an interesting challenge to say to myself, “I don’t think I should take what this one artificial intelligence engine is giving me, but I could combine it with others and make them collaborate and feed back to each other.”

I used three models and thanks to that combination I was able to give my original idea a life and essence of its own. As designers we always have the challenge of having an idea, and in the course of being able to materialize it we have a lot of possibilities of tools and new media to be able to transmit it. I wanted to make a tribute to everything we have and everything we enjoy, always being aware that we don’t know when is the last moment we will be able to enjoy it. And I’m not just talking about the natural and tangible environments, but also that our own tools as designers and artists are changing. The Photoshop we used to know, where we could spend hours removing a background, now artificial intelligence is included and in two clicks it removes the background and then you have to adapt to these new times, to these new speeds, and to the new results that technologies are giving you. All this can help you and give you many more possibilities to develop your creativity.

“Now most artificial intelligence engines ask you not only for a prompt but also for a context, a story, an aesthetic.”

Part of the process of working with AI is the use of language, through the prompts with which the images are generated. For me this has been very interesting, because I like writing very much, I have always enjoyed writing and it is one of my best ways of expression. I have always considered it necessary to accompany the visual pieces with text to communicate what I wanted. Now most artificial intelligence engines ask you not only for a prompt but also for a context, a story, an aesthetic, with a description as extensive and precise as possible of what you want to create. The program adapts more and more to the subjective, to the associations of ideas, and in this way gives you results that are less and less strange or sinister and more and more familiar, with which it is easier to connect. You have to narrate a story to it, and then tell it “from all this that I’ve told you, create an image of what happens when this or that happens.”

At the end of the day, that’s what we designers and artists do, we create a story and share it through our own experience but always looking to connect with those who will experience it. Then you have to keep in mind that you have to work with different AI models, for example one that can enhance your prompts to be better understood by another AI engine, or one to work on color or lighting. It’s a new process that you need to adapt to.