Pau Waelder

This interview is part of a series dedicated to the artists whose works have been selected at the SMTH + Niio Open Call for Art Students. The jury been selected at the SMTH + Niio Open Call for Art Students. The jury members Valentina Peri, curator, Wolf Lieser, founder of DAM Projects/ DAM Museum, and Solimán López, new media artist, chose 5 artworks that are being displayed on more than 60 screens in public spaces, courtesy of Led&Go.

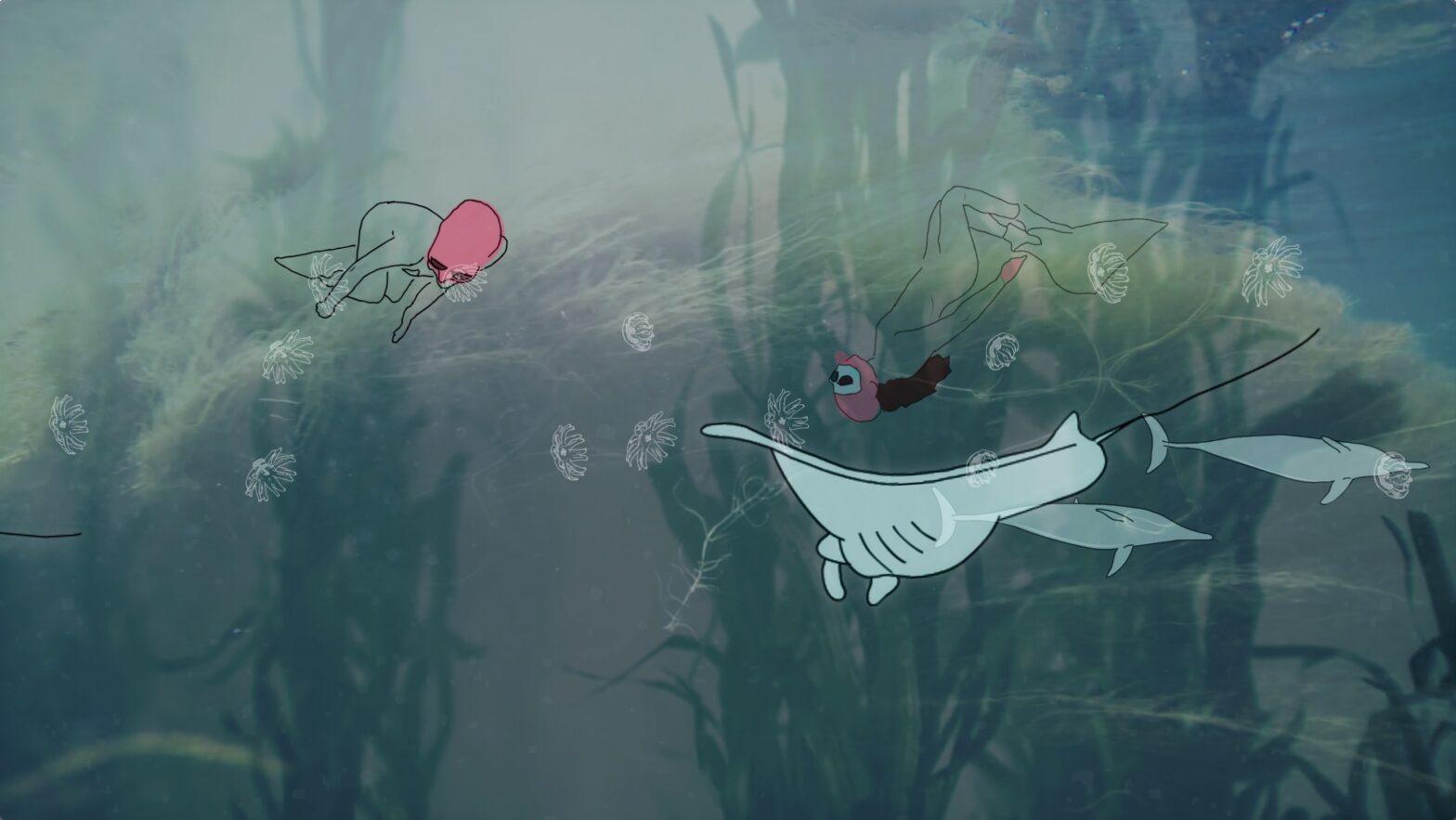

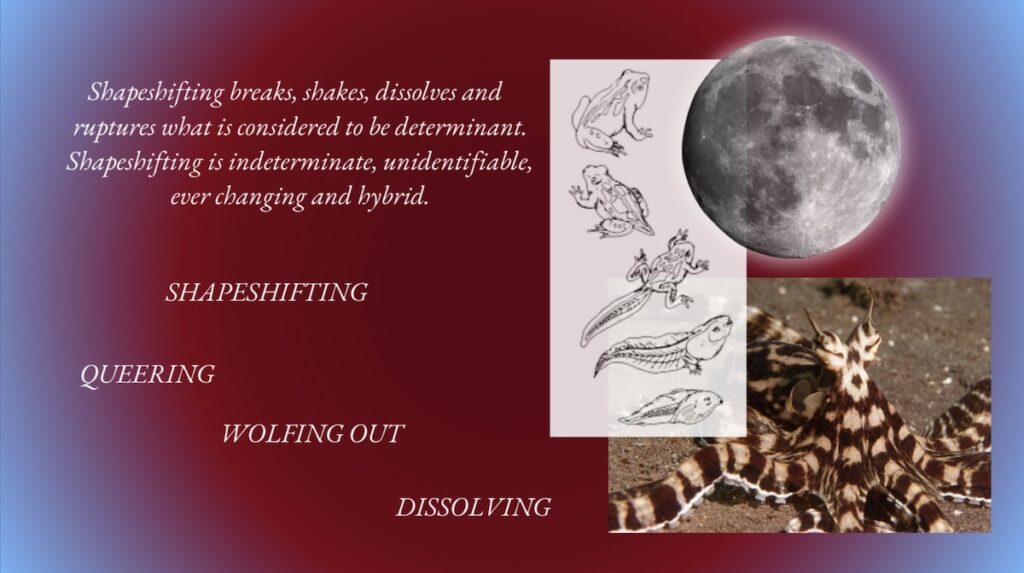

The artist duo Cruda Collective, formed by Laila Saber Rodriguez (CAI-CDMX) and Andrea Galano Toro (CL, ES), creates ways of re-thinking established narratives and mindsets through what they describe as rewilding practices: “ to activate the wilderness, playfulness and the glitches within storytelling & mythology.” They approach the world, aesthetic, and language of magic to address the non-normative through playful action and critical thought. Their artistic practice mainly consists of audiovisual performances, videos, workshops, and spell-casting.

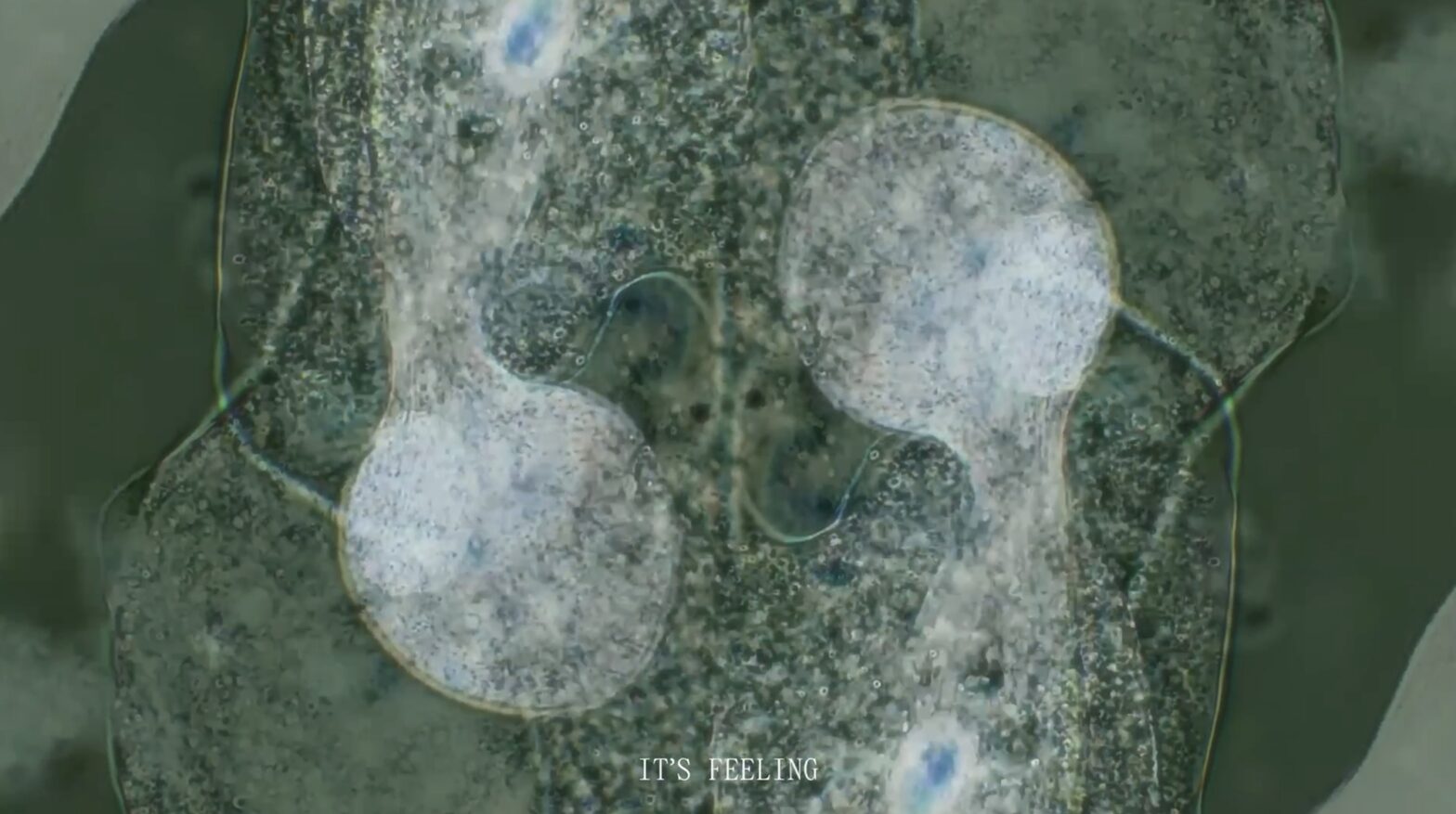

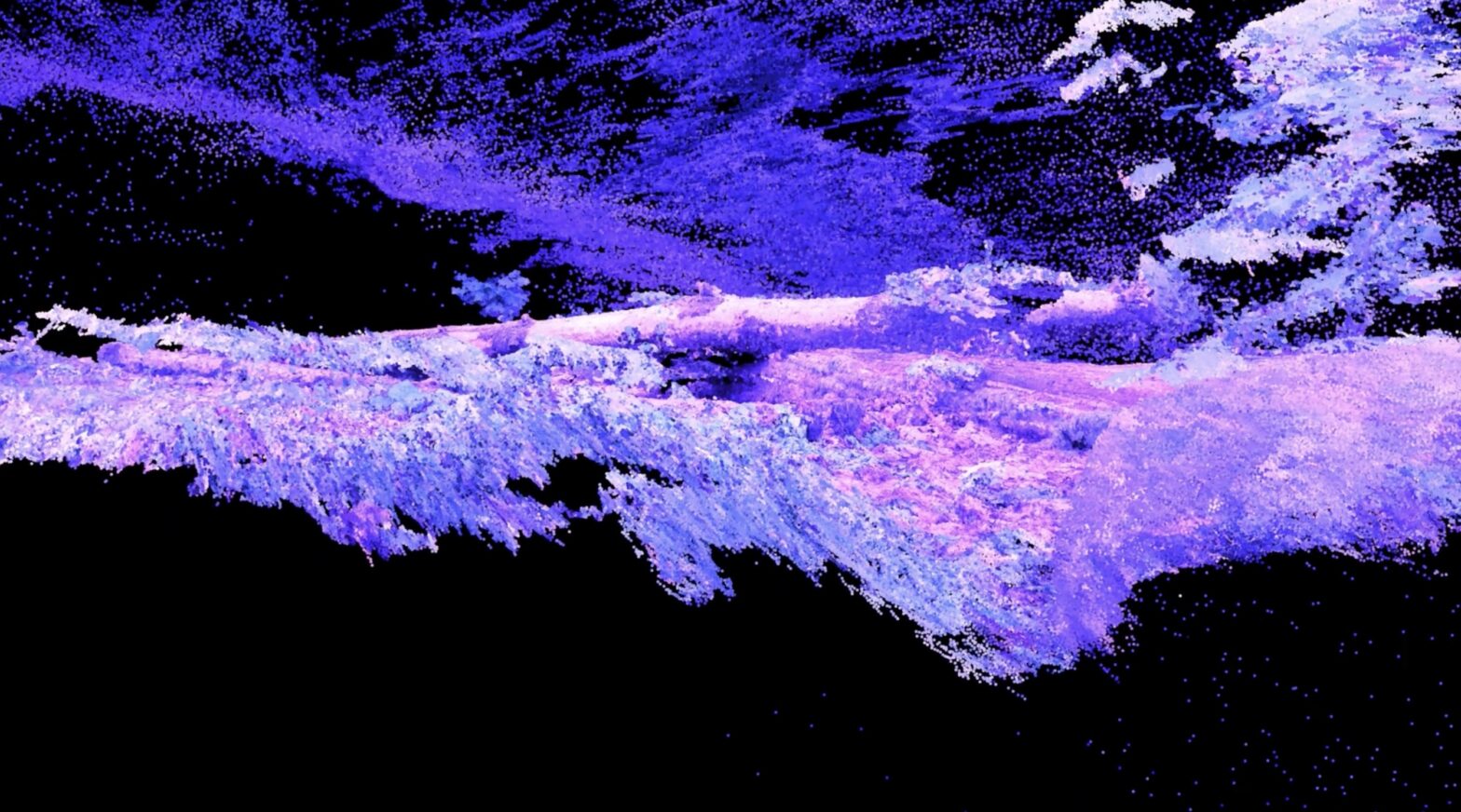

Cruda Collective. Re-Rooted, 2024

Your work deals with magic, hybridity, transformation, the non-normative, wild, unseen, and obscured. You address these fields of knowledge and existence through workshops, bestiaries, performances, and spells. How do you deal with the dichotomy between the untamed and the systems of order and rationalization behind analytical practices such as making a bestiary or a cartography, and the necessary application of rules and consistent methods in the elaboration of a workshop or a spell?

Andrea Galano: We are fascinated with the processes that have a certain order, because we’re very interested in transformation. We like to adopt processes such as those involved in cartography, or burial too, which have a certain method or ritual. We then switch the narrative, still within that particular method, to talk about transformation or spells: we appropriate certain structures or ways of ordering. It is useful when you’re talking of things that can be ungraspable.

Laila Saber: In order to apply a method, an order, or an analytical practice, we need to be involved and interact with that practice or method in order to break it and disrupt it. And we also consider how the incomprehensible or the disorganized, the disobedient as an archetype, or as a process is what can create new models and new systems of knowledge. We reference a lot the concept of “Body without Organs” by Deleuze and Guattari: how can the breaking down of the body, and the normal functions of the organs, address new maneuvers and new functions of the body? And then how can it produce new models of thinking?

Andrea Galano: Mappings, rituals, the functions of the body… These are things that create the world we live in. So if we transform them, then we are somehow creating other worlds.

It seems that we are always attracted to chaos and everything that is mysterious or hidden, but at the same time, we need structures to understand these “untamed” aspects of reality. How is the experience of people who are in your workshop, what are their expectations, and how do they react to the methods that you suggest to them?

AG: Sometimes we start with something that is very playful, not knowing yet what you’re going to do with what you’re making. And then later we ask them to think of a narrative with it. So rather than thinking of the concept, and then making something, sometimes we do it the other way around, just to see what happens. This is the method that tends to work best, first doing hands-on or embodied exercises, and later on asking participants about the narrative and perhaps bringing in theory.

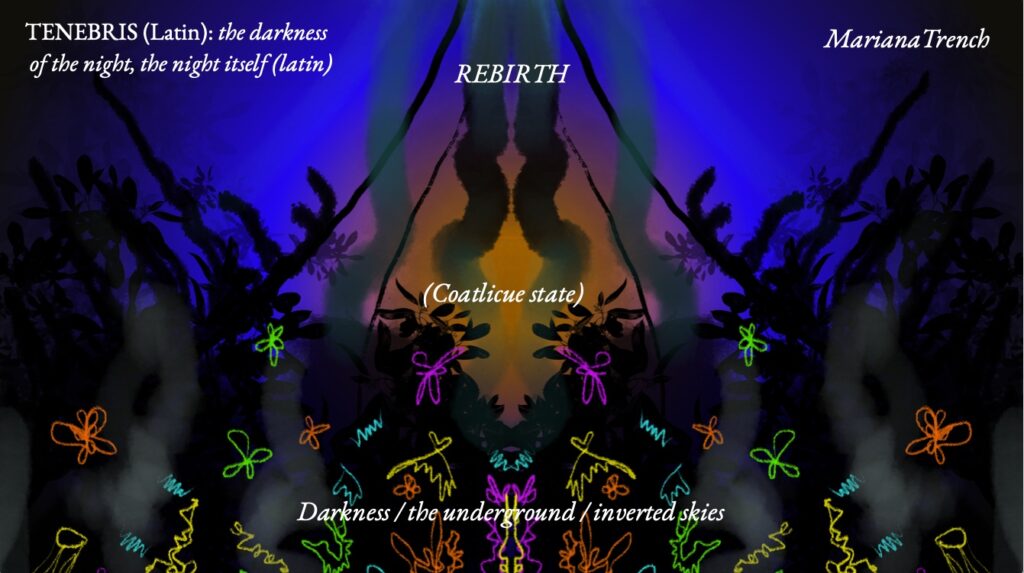

LS: I think most of our participants are from the art world: they are makers, or creatives, or artists and designers. So it becomes super interesting to propose to them to think with their hands and think with the body rather than with the rationale of having to produce a perfect product. By starting with this uncertainty and playfulness, we also ask them to defy the linear structures that makers are so conditioned to go follow. We actually just start all the workshops by saying: “Okay, today we die. Today everything is gonna die.” We start with death, and from death everything begins. We read really beautiful texts specially written by Gloria Anzaldúa on Coatlicue and Mesoamerican deities, which are all about transformation and rebirth.

“Mappings, rituals, the functions of the body… These are things that create the world we live in. So if we transform them, then we are somehow creating other worlds.”

Andrea Galano

Writer Alan Moore has said that magic was once “a science of everything,” and that “If magic were regarded as an art it would have culturally valid access to the infrascape, the endless immaterial territories that are ignored by and invisible to Science, that are to scientific reason inaccessible, and thus comprise magic’s most natural terrain.” Would you agree to this connection between magic and art? How do you see this idea from the context of your artistic practice?

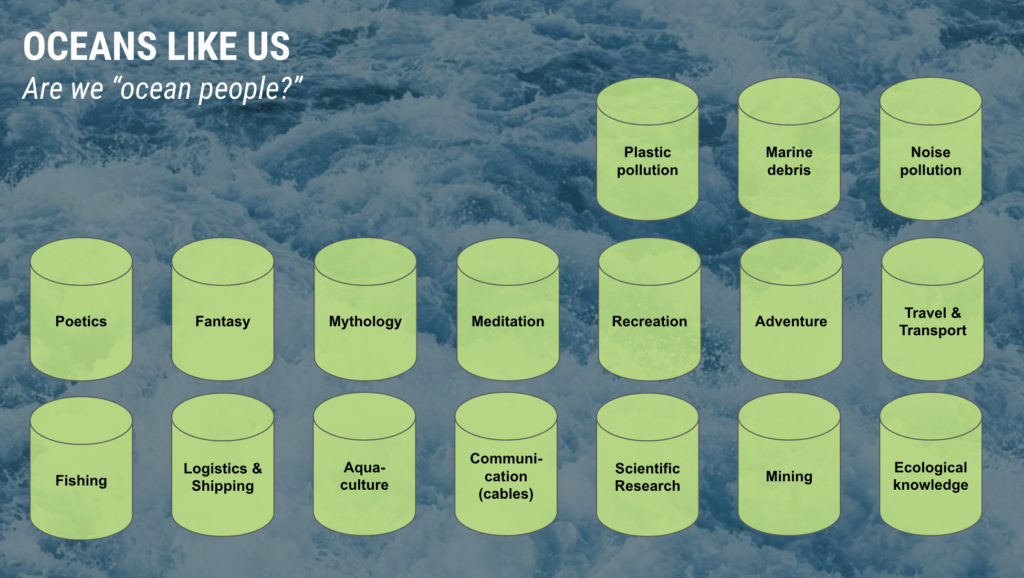

AG: It is true that there’s a certain first reaction or expectation that we’re going to talk about, I don’t know, paganism. Which anyway, we find very interesting, but it’s not in the way we are approaching it. However, this is good because it creates this reaction of “oh, but what is it gonna be about?” That is an interesting starting point. Also, for example, we always talk about knowledges, in plural. There are many ways of thinking that coexist, and have coexisted in the past, but perhaps were erased or they’re not part of the main Western narrative. So already thinking that there are other alternatives to this monolithic Western thinking, becomes very intriguing to the participants, and also to ourselves. We are very interested in different fields of knowledge, such as biology or ecology, and we find that some of the processes they study are very magical. For instance, the fact that something new can emerge out of two separate things that were put together, that feels like magic.

LS: Something we’ve also been working on is how magic animates worlds and landscapes or elements. We imagine what it would be like to engage in a conversation with, for example, the ocean or the mountain. What can those bodies tell us about the world we live in? And how, within that conversation, another world can emerge? And I would say that magic is another word for speculation or imaginative thinking, engaging in a really beautiful and often confronting or disruptive way of thinking and acting. In this way, we can apply Magical Thinking to everything, not only science, but let’s say cooking, business, or politics. In all discourses there is the possibility of redirecting what is expected and opening new paths to creative thinking.

“Magic is another word for speculation or imaginative thinking, engaging in a really beautiful and often confronting or disruptive way of thinking and acting.”

Laila Saber

Similarly to how science has undervalued magic, as Alan Moore states, it has often dismissed art and artistic research. When you approach science, how is your connection to art and magic perceived? Have you had this discussion with scientists?

AG: There are many people from the sciences that are very inspiring to us, such as Karen Barad, who has a background in quantum physics. We do find references from science that resonate with us, and at the same time we’ve had workshops where some participants were scientists who found it very interesting for them to actually play and think of something that didn’t have to be real or measured.

LS: It’s in the symbiotic fusions between disciplines where we can find interesting models and new forms of seeing the world. I don’t think that, as artists alone, we can make those changes, and neither can biologists alone. We need to have conversations, and work together to open up these worlds, which are often isolated and self-referential. It also comes down to the language barrier: the way we speak, as artists, is very different from the language of science, and of course we need to find ways of understanding each other.

You take the concept of rewilding beyond the sphere of the natural sciences and the environment to encompass a rewilding of our inherited ideas and dogmas, particularly in relation to a society driven by Western colonialism and patriarchal structures. Can you elaborate on how your work addresses this expanded notion of rewilding?

LS: We like to think of rewilding as a practice of planting new seeds. Just as in an ecosystem or a rainforest, seeds travel and grow into plants, bushes, and trees, by communicating ideas we are planting something that ultimately will regenerate the terrain. These ideas mingle and all the new thoughts, disciplines, and discourses entangle within one another. In this way, rewilding is a portal into other possibilities of what there is, both in the natural world as in society and in our mindsets.

AG: The artist Johanna Hedva, who works a lot with witchcraft, once said: “It’s no coincidence that as capitalism began to take root, a regime of colonial exploitation started to run amok, de-enchanting the world. If the world is seen as a lifeless resource, it can be mined without compunction.” In this sense, rewilding is re-enchanting, not only in terms of ecology, as Hedva suggests, but also culturally and artistically, connecting with those cultures that celebrate the enchantment of the world and have been sidelined by post-colonial Western rationalism. In these cultures and in the concept of rewilding we find a more sustainable relationship with our planet

“Rewilding is a portal into other possibilities of what there is, both in the natural world as in society and in our mindsets.”

Laila Saber

Your interest in beasts and shapeshifting brings to mind Donna Haraway’s concept of the Cthulhucene, with its tentacular, earth-bound, promiscuously hybrid forms as a response to the rational, human-centric view of the Anthropocene. How does your work relate to Haraway’s concept, and subsequently to our relationship to the environment?

AG: Haraway also talks about kinship with other species. We relate a lot to this idea: when we talk about bees or hybrids, there’s definitely this kinship with other beings. Also, in the spells we write or perform, we usually embody creatures that have other forms of communicating, such as bioluminescence, or the snake shedding its skin…

LS: In terms of the Cthulhucene, we are also interested in the chthonic, which relates to what lies under the earth or soil. We’ve been recently researching on our last workshop about this, the underworld and the gestures and acts of burial. We have found inspiration in the book Underland by Robert Macfarlane, in which the author speaks about Anthropocene unburials: “Forces, objects and substances thought safely confined to the underworld are declaring themselves above ground with powerful consequences.” We are a species that buries, and also a species that digs, and in our exploitation of the Earth’s resources, what was buried comes back to the surface.

Process and narrative can be said to be driving elements of your performances and workshops. How do these two concepts translate into your videos? How does the video, as an audiovisual narrative passively consumed by a spectator, connect to your other forms of knowledge transmission and active participation? What do you expect of the video as a medium?

AG: We’re very drawn to video because it has the capacity to build a particular world and, when it is combined with sound, it can create an immersive experience. We love storytelling, and we find in video a way to play with narratives and also a dissonance between what you see and what you hear. In our video pieces we aim to take the viewer through a certain journey, and also give them space to process their experience.

LS: We often refer to our video artworks as portal openers. The term “video” sounds very limiting, so we try to use this medium to bridge different narratives and suggest new meanings, subvert expectations. We like to think about forms of nonlinear filmmaking, fluid filmmaking, a kind of storytelling that is sometimes slippery, that sometimes leaves you wondering what is going on.

AG: Another aspect of video that attracts us is the possibility of working with different levels of perception, from images of the cosmos to those of a microscope. Also with audio, we can play with very different sources to create a hybrid of contents and meanings.

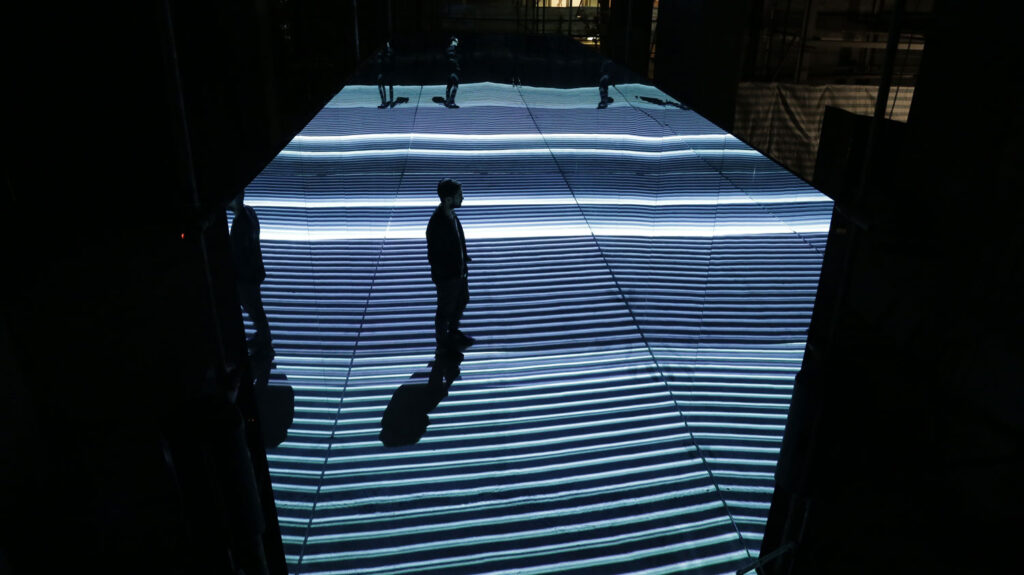

LS: Our practice is also evolving in this sense, we are increasingly interested in creating immersive experiences through audio visual performances where we have both visual and sound as we’re performing. We often describe our videos as “spells” because our performances and videos are actions of enchantment, and as a video piece, this action becomes a spell that is out there and can be activated by any viewer.

Since your work addresses that which is outside of the normative and established, how do you see the possibility of taking it out of the exhibition space, the cultural institution, and into an everyday commercial space as is the case in this distributed screening project with SMTH and Niio?

AG: This is something new for us, and therefore it is also exciting. As we were saying earlier, playing a video can be like activating a spell, enchanting a place, so I’m curious to see if it resonates with the people in these spaces or not. In any case, it is occupying a space where it is not expected, and that is interesting in itself. I also think that it is important that the artworks do not only stay in the galleries or in spaces dedicated to art and presented to an art audience.

LS: It feels magical to have this artifact existing in several spaces, having a presence in these commercial locations. In a way, it is like breaking a curse, maybe the colonial curse, the capitalist curse… It is about rewilding too, in this shopping mall in which it may not be seen or understood, but it will still be there, and possibly prompt questions, reflections, or experiences.

“Playing a video can be like activating a spell, enchanting a place, so I’m curious to see if it resonates with the people in these spaces or not.”

Andrea Galano

You are currently students at Bau and Elisava Design Schools in Barcelona. What is your experience of the educational models in these schools? How do your studies inform your artistic practice? What is your opinion about the current perception of artistic research as a field of knowledge creation?

AG: We come from different studies in the past, and now we are also in different studies in our respective schools. As for me at BAU, I’m doing a Master’s Degree in Audiovisual and Immersive Spaces. And I think I can only speak for my master rather than the school, but I’d say we’ve learned a lot about having a critical approach to the ways of making. I think that’s very interesting, because it’s not so much about the topic or the concept, but about the tools you use, such as open source software or making your own electronics. It is also a very collaborative environment. Being part of a community that is open to sharing knowledge is an eye opening experience that helps you get rid of the old-fashioned idea of the artist as the sole creator of their work.

LS: I studied Fine Arts in the Netherlands, in a super good program, which involved a lot of theory, so we read Deleuze, Foucault, Haraway and many others as part of our studio practice, and I think that set the foundation for my ongoing studies at Elisava Design School in a Master’s Degree in Art Direction and New Narratives. I do feel that there’s a gap between making and keeping with a critical speculative practice that is really valuable in any artistic research. In that sense, it has also been interesting for me to be immersed in a space that is really focused on functionality and communication. I’d say that this has led me to be more receptive or more agile, so I can sense what it is exactly that I’m disrupting or trying to disrupt eventually. I also find it valuable that my classmates are from different nationalities, which brings an intersection of multiple cultures, that helps a lot in working with the concept of new narratives.

ReRooted presents an interesting take on the patriarchal notion of masculinity from a wider perspective that connects with the notion of rewilding ideas and avoids traditional imagery about masculinity to suggest addressing this subject from the perspective of living beings and natural systems. It is also connected to a workshop activity. Can you elaborate on the context and intentions behind this audiovisual artwork?

AG: In this artwork it is important to mention our collaborator the writer Virginia Vigliar, who hosted a workshop titled ReRooted: an ecological approach to masculinity. It is in the context of this workshop and our conversations with Virginia that we decided to create this video. It takes elements from discussions we had with participants in the workshop, with some quotes making it into the video itself. It was challenging for us to decide which imagery to use, since we wanted to disrupt traditional views of masculinity.

“We need to reconceive masculinity as not being patriarchal per se, and explore those micro stories of masculinity that are hidden.”

Laila Saber

LS: We spoke a lot about how we are all affected by the patriarchal archetype of men and the patriarchy. Virginia’s approach in the workshop is to uproot myths in our stories surrounding masculinity, and rethink them. Actually, we came to say reboot it, because we need to reconceive masculinity as not being patriarchal per se. For the visuals, we decided to focus on microscopic imagery and then macroscopic images, from the cosmos. And in bridging those two, we were trying to reflect on how masculinity has its macro stories, which form a big corpus, but also micro stories that, perhaps, are hidden, and you can’t really see until you zoom into them.