Pau Waelder

Rune Brink Hansen (Denmark, 1979) is a digital designer and artist who has developed a career in web design, 3D modeling and VJing since the early 2000s, creating stage design for operas, concerts, and festivals, as well as spatial design for museum exhibitions. Since 2010, he has created a wide range of immersive and interactive light installation pieces in Danish galleries and museums and has also worked as curator in several contemporary art projects. In May 2021, he created Spøgelsesmaskinen (“the ghost machine,” in Danish), an alter ego and a specific project for the NFT scene that focuses on creating short 3D animations in a distinctive pixelated style that depict surreal and eerie scenes involving computers and other machines. After successfully selling his NFTs on Tezos, Ethereum, and Solana, he is now preparing screen-based pieces to exhibit in art galleries.

On the occasion of his solo artcast Abnor Mall, we spoke about his career, his aesthetic and conceptual choices, and the influence that the NFT scene has had on this production and creative process.

You are known for your interactive and kinetic light installations, which often create a novel experience of the surrounding space. What interests you about working with light and the architectural space?

I have always been interested in telling a story in a different way than you would normally find in a movie or a book, a way in which you can become the main protagonist of an experience that the story creates. I have done a lot of installations for cultural heritage museums, and in them I’ve tried to develop a visual language that would keep a certain level of abstraction, in a way to focus on telling the story. And then by doing spatial projections, or light installations, I have created a landscape around the visitors that would trigger their imagination to feel that they are the main character of the story, instead of watching something at a distance. For instance, if I had to depict a war zone, I’d rather create an atmosphere of anxiety and work with the feelings it generates rather than show images.

So I would say that this is the reason why, when I started to work in art installations, coming from a design background and then doing visuals for music, I decided to create these spaces for the audiences where they really feel immersed and not just watching someone else. I have always been hesitant to create a narrative that is too defined and detached from the viewer, even when I did live visuals for music. I didn’t want to create a perception of the music that was too concrete, too pre-defined.

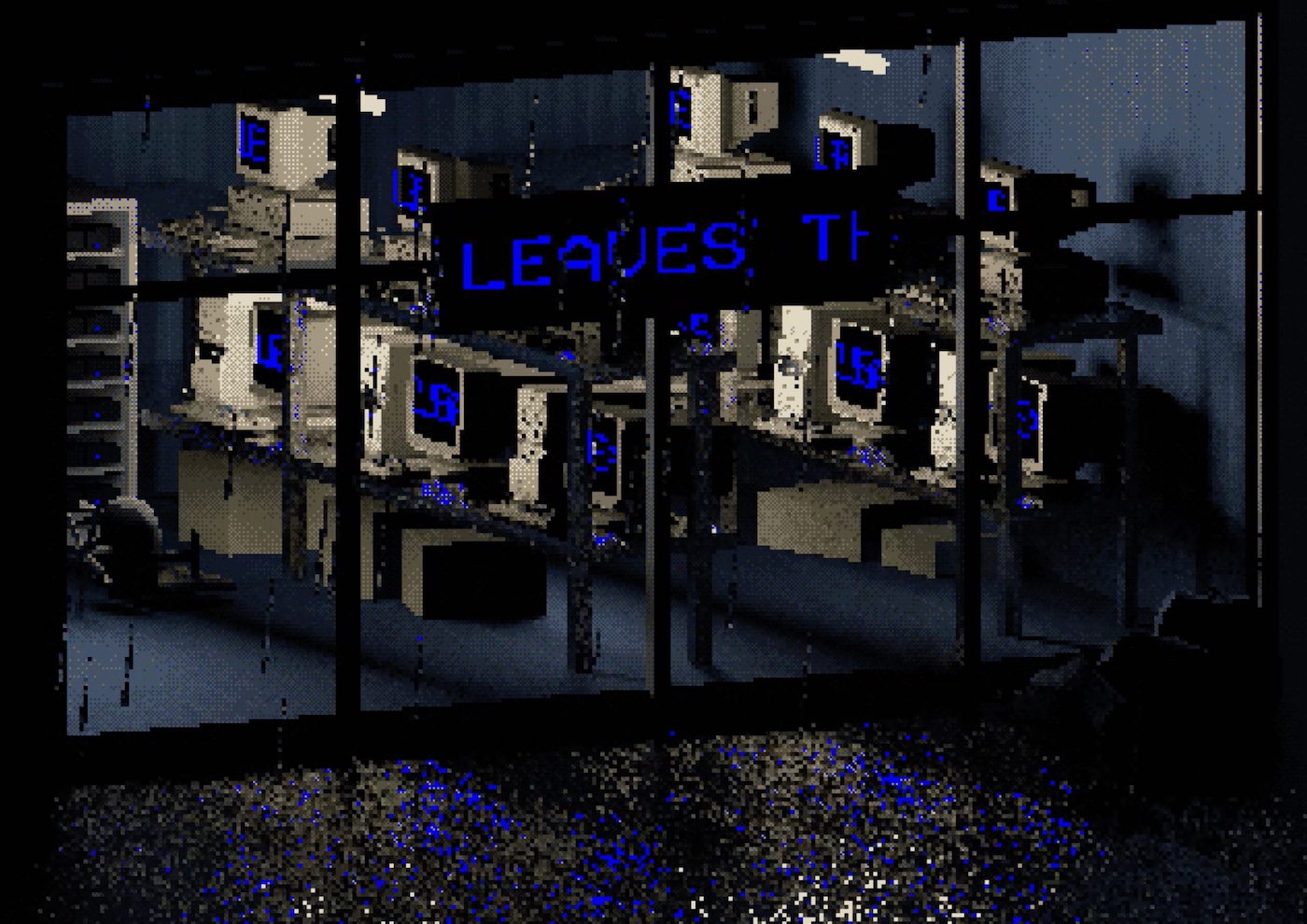

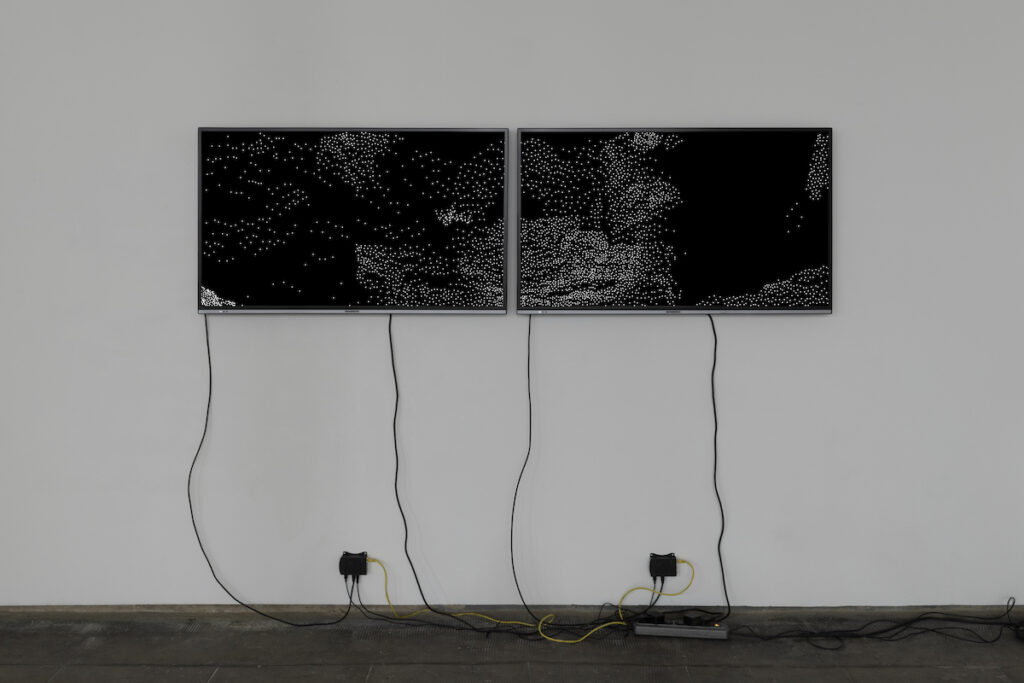

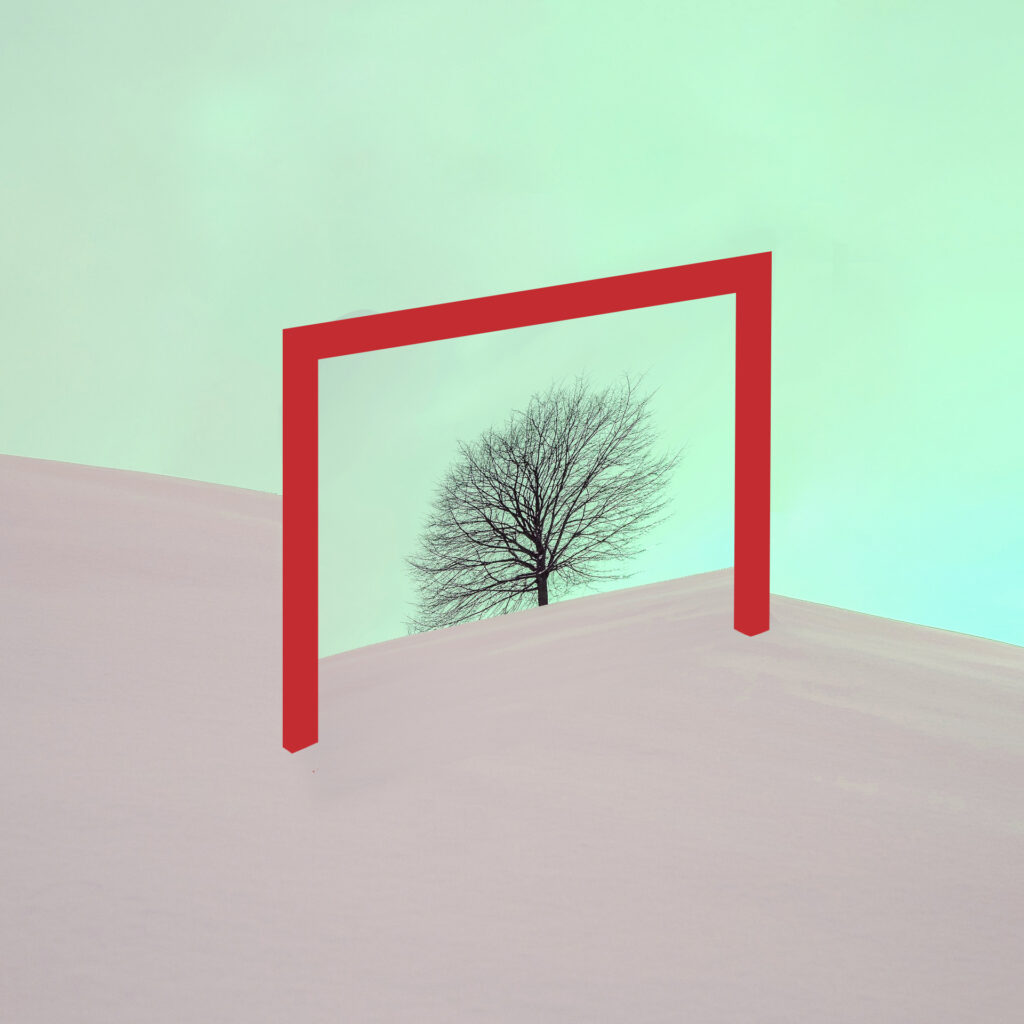

Spøgelsesmaskinen. Abnormall: Parking, 2022

The animations you create as Spøgelsesmaskinen usually depict scenes in carefully set up spaces, how do they relate to your artistic installations?

In 2009 I did a stage design for the opera Konsumia by Rasmus Zwicki. The story was about a group of people trapped inside a digital illusion. The opera singers would have to sing to make sure that the computer controlling the illusion couldn’t understand what they were talking about. All of this was situated in this dull, eerie, office landscape that represented the capitalistic world. I did the stage design in the exact style I’m now using with Spøgelsesmaskinen, with non-antialiased, very hard pixels and low resolution.

So I thought, okay, I would really like to go back to this world. It was really a very nice world for me to work in. So that led to what is Spøgelsesmaskinen, basically. And then things started to take off, I started to go into different directions, but I also went back into doing more abstract experimentations. But obviously, the style that is identified with Spøgelsesmaskinen comes from stage design and probably that is why they look like tableaus, in small spaces, although without any characters. But there may be a spirit somewhere in the room…

“The style of Spøgelsesmaskinen comes from stage design. That is why they look like tableaus, in small spaces, although without any characters.”

Spøgelsesmaskinen means “The Ghost Machine:” why did you choose this alias? Is that connected to the idea of “the ghost in the machine” and the use of glitches?

In my early childhood, maybe at the age of eight or nine, the first computer came into my home. To me, the computer was always surrounded by mystery, an uncanny feeling. The computer was in a corner of my bedroom. I was in my bed at night, and I was looking at it and just expecting it to wake up on its own. Because for me, this was magic. In Microsoft DOS, there was this application called Q Basic, where you could write small applications. And I wrote my first chatbot, which would just reply to different prompts. And I could sit for hours chatting with the bot, having a pre-programmed conversation, and feeling that there might be a spirit in this machine, somehow. This continues coming back to me: the complexity of the machine is still enough to fool me into believing it’s alive, in a way.

And how do the glitches come in?

The glitches are what the computer does that is unexpected to the human. I guess that’s why glitches are celebrated, especially right now, as the computer’s capability of being an artist on its own, in a way creating things that are unexpected. Design today is very inspired by how HTML is wrapping different boxes around and making mistakes. There is a huge trend of putting text on top of images halfway, all these different things are coming out of what the computer can do. And so the glitch is proof that the computer is superior or that the computer can surprise us.

“The complexity of the machine is still enough to fool me into believing it’s alive, in a way.”

In relation to this ability of the computer to create, now that artists are increasingly integrating AI tools into their creative processes, are you interested in this possibility?

Yes, certainly. I recently did an installation for YOKE with AI Sweden for the Nobel Prize Museum’s new exhibition, Life Eternal, at Liljevalchs art gallery in Stockholm. The installation is based on GPT SW3, a Swedish version of the GPT-3 generative language model, and used the text of the novel Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro. Visitors can have a conversation with an AI system modeled after the protagonist of the book on the theme of eternal life. So, I have worked with AI in the facet of my work related to installations and stage design, but not yet as a tool to create visual compositions. I’m very open to doing so, but I just haven’t found the right opportunity.

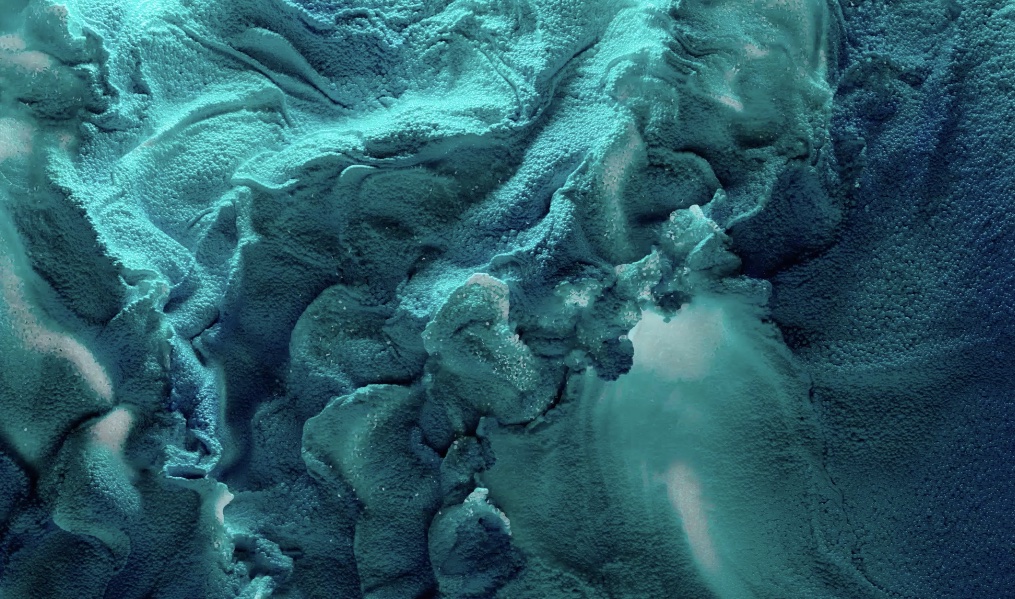

Spøgelsesmaskinen. Abnormall: Electro, 2022

The aesthetics of your work as Spøgelsesmaskine are clearly influenced by computer graphics from the early 1990s, which is about the time you started doing 3D animations before becoming a graphic designer and VJ. How do all these experiences collide in your present work?

I have this background as a graphic designer, and then I’ve worked with a lot of installations, festivals, and live events, building big physical installations that are very costly, so I’m used to dealing with all the pressures and limitations, making sure that things are not coming down from the walls or that I don’t go over the budget. In this work with 3D animations I feel that I have the complete freedom to do anything I want, to experiment in any crazy way I like to. And sometimes it seems to me that I am also sketching physical works to come. So in a way, they are a sort of doodle, or a sketch. Even though they are self contained pieces on their own.

“The glitch is proof that the computer is superior or that the computer can surprise us.”

Your low pixel resolution work becomes instantly recognizable. Do you feel that in an environment saturated with images, and particularly in the NFT community, with many similar artworks, it is important to stand out with a distinctive visual style?

Yes, I’m trying to stick to it. Because I feel that it’s becoming my signature. And I never really had a style before, I never drew, or painted. So it feels like I’m finally coming to a place where I can connect with what I create very easily. Working with 3D has always been limited by the looks of the final render, because the final render never looks like reality, it’s very hard to make it look realistic. And so I’ve always been struggling with 3D, but now I found a render style that is actually taking me into a more humble space. I think it was p1xelfool who said that the lower the resolution, the more connected to the machine he felt. I agree and I think that working in low resolution is a way for us to feel this craftsmanship and also to feel that the computer is not overdoing it, that you can still be in control. It’s not this hyper technological thing that you need the robots to do it for you. It is also a way to say: I don’t need 204k screens, I don’t need to buy new things all the time. I can work with what I have, what has been here for a long time.

In that sense, you have mentioned that you find a lot of 3D models in libraries of objects that no one uses anymore, and that you include in your scenes.

Yes, there are so many 3D models on different platforms that represent different times in history, for instance old mobile phones that are not being used anymore for the commercial purpose they were built for. So it’s a fun way of diving into the history of 3D models, and it’s interesting to see how much time and thought went into modeling all these objects that are now lying in digital junkyards.

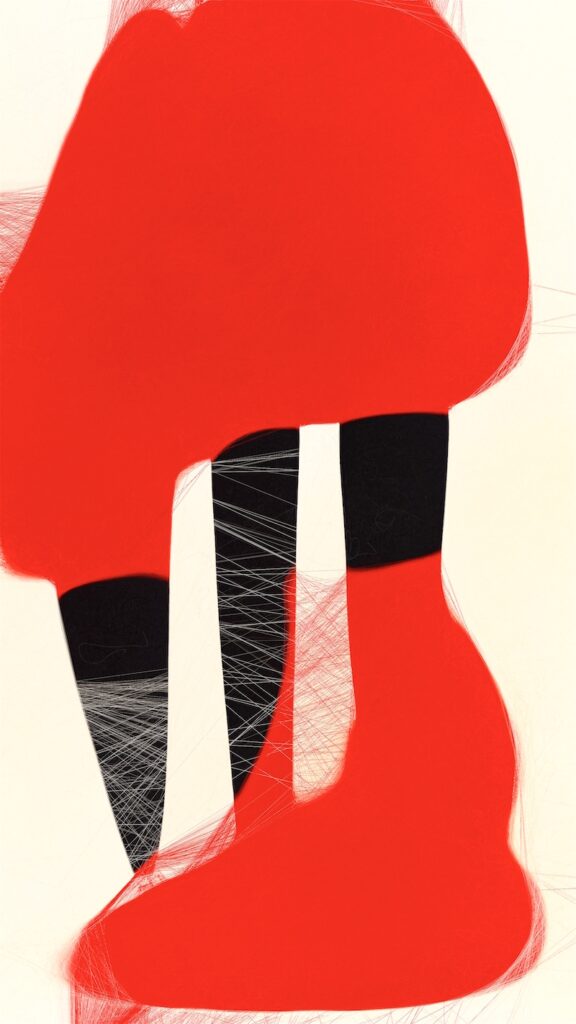

Spøgelsesmaskinen. Abnormall: Flash, 2022

So, to better understand the process, you create the whole model in 3D, and then you apply the rendering in a very low resolution, is that correct?

Yes. For some of the scenes I’ve used all these different 3D models I’ve found and put them together, and for others I model from scratch because I need to build a specific scene. Then an interesting thing happens with the loss of information when rendering at a low resolution: sometimes it doesn’t look good the first time, and I have to change the objects, the positions, maybe zoom in more, get more or less details, and so on. I render them in 320 x 240 pixels and scale them up frame by frame, to double the size, and then turn them into GIFs. I think Photoshop is getting rid of GIFs, so maybe soon I will probably have to start working on older machines to actually be able to run the software

Right now I’m working with a company that builds LED screens and I’m doing tests to have an animation run in the screen at the exact size, each pixel an LED, with no scaling, a sharp image. For that I need to avoid any form of antialiasing, which luckily can still be the disabled in some software.

You have decades of experience with 3D imaging and digital creation tools. What do you think about the development of digital technologies for creatives? Do you consider that open source software has had a major impact on creativity?

I wouldn’t be able to use abandoned software and hardware in the future if there wasn’t an open source community. I did a small project called Memory Leaks in which I worked on the Classic Mac OS. And that was only possible because of the community that is still putting up the software online, hosting it, and making it available for free. The same goes for the 3D models. I’m working on a series of assets for people to create their own scenes. So I’m planning to do a series in which every model is made by me from scratch and everything is released for people to use in different ways.

“The NFT scene has changed my life completely.”

What has the NFT market brought to your practice and its sustainability?

It changed my life completely. I went from working freelance for museums, and very rarely doing my own installations, maybe once a year, to only being on my own now. So it has completely changed everything. In Denmark, there is a lot of interest in blockchain because it is still so new and few people work on it. So basically every week, I have five phone calls with organizations asking me how they can implement blockchain and what they can do with it. I started a small think tank with two friends of mine, called Korridor.digital, which is a shared workspace for blockchain projects in the field of art. We try to help other artists, we do workshops. And we just recently moved into an art foundation where we are now helping to consult in this field.

My network has really changed, I have made so many friends all over the globe in the last few years, and such a huge network, having places to crash in all the major cities of the world, that it is completely mind blowing, and amazing. Even if NFTs are a capitalistic project, they have become a huge social movement. I also worked for some time on the Afghan NFT project where we try to raise money for African artists and Africans in general in need. About 50 artists donated works, and we raised around $18,000. Unfortunately crypto is currently banned there.

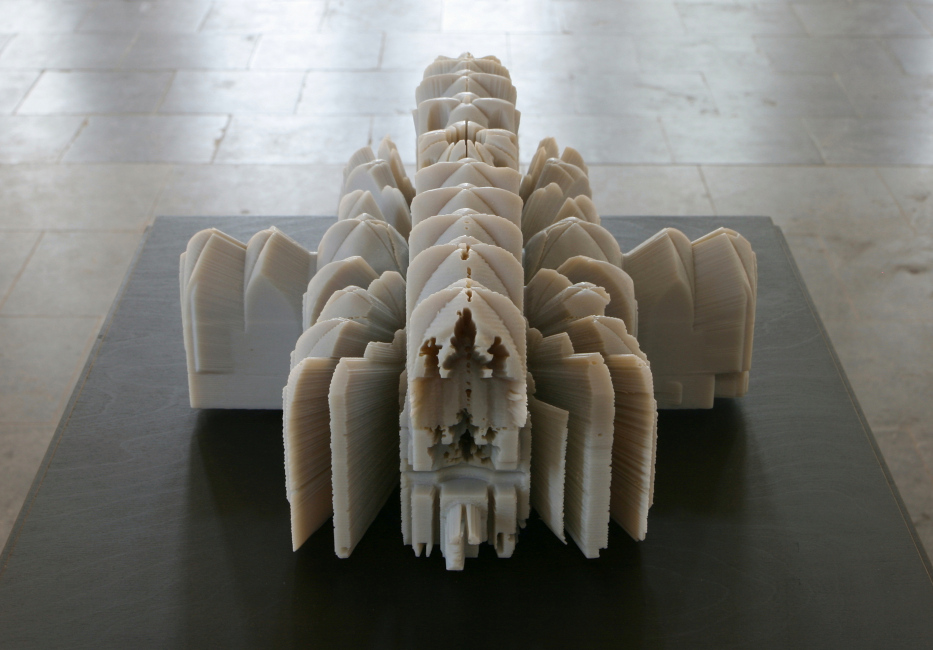

Spøgelsesmaskinen. Abnormall: Escalation, 2022

You work under two different names, one of them specifically directed to the NFT market. How does that affect your practice? Can you balance both aspects of your work?

I don’t know. What should I do? Help me! The Spøgelsesmaskinen project is growing, now I’m going to do exhibitions in Copenhagen, so I guess I will start to work with some specialists who can help me out a little bit. Because I recently did a permanent light installation in a park which is like a playground where you can play with light, and that has really nothing to do with the concept of Spøgelsesmaskinen. So for me it is good to have these two names and separate the kind of work that I do. Being online as a different person that is not related to my real identity or my personal life is very interesting. And starting from scratch Twitter and Instagram accounts that are now outnumbering my other accounts, this gives so much energy. So in that sense, I am enjoying the freedom it gives me to try out something new.