Pau Waelder

With thirty years of experience, Wolf Lieser is one of the most veteran art professionals in the digital art market. A visionary gallerist who saw the potential of digital art early on, he supported pioneers such as Frieder Nake and Manfred Mohr and later on some of the most celebrated artists from each decade, from Lynn Hershman Leeson to JODI and Casey Reas. His work is not limited to representing artists from his gallery, but also spans influential projects devoted to educating audiences about the history of art and digital culture, such as the DAM Museum, the DAM Digital Art Award and two books providing a comprehensive introduction to digital art.

We sat down to talk about his work and experiences on the occasion of the ongoing collaboration between DAM Projects and Niio, which has brought to our platform the work of Eelco Brand, Driessens and Verstappen, and Tamiko Thiel.

Your first contact with digital art was in 1987. What interested you about contemporary art before that, and how was the transition to digital art?

I started working as an assistant for a painter, then I became an art consultant, and later on in 1993, I founded my first art gallery. As an art consultant I was mostly developing art projects for companies, curating exhibitions and taking care of everything related to them, from art leasing to organizing workshops or lectures. It was a broader activity always oriented towards the purposes of the marketing department of the specific company. That had not much to do with the typical art market, which involves collectors, museums, and art fairs. It was only later on that I decided to concentrate on the typical gallery game, which involved artist representation, a regular exhibition program in my own space, and mostly dealing with customers and collectors.

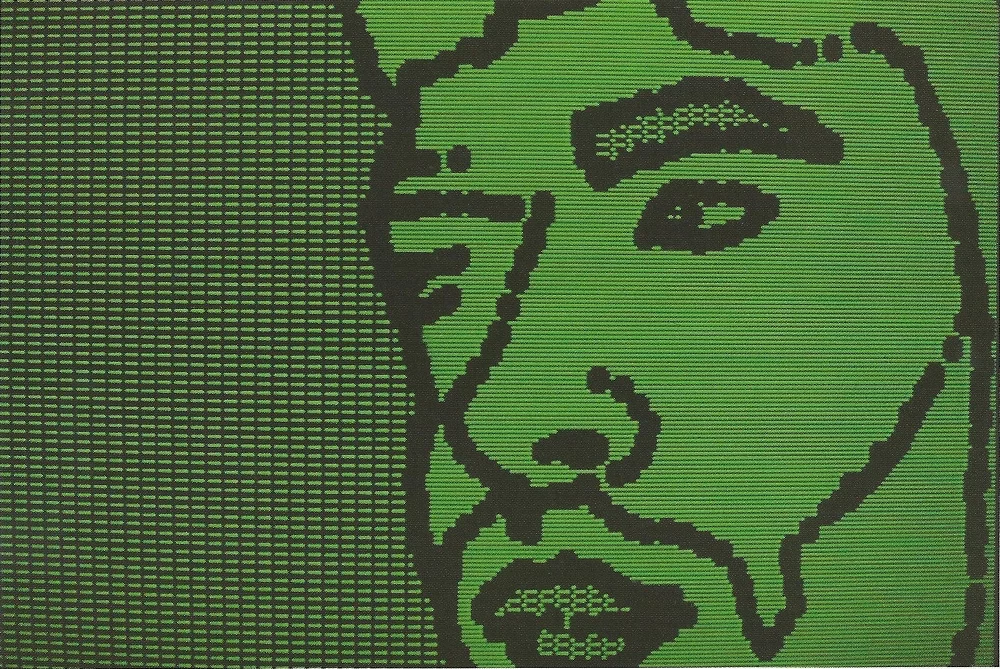

The gallery was in Wiesbaden, near Frankfurt. When you start as a young gallery, and you don’t already have good connections in the art scene, you are not able to reach out to the most valued artists at that point. You have to build a reputation, and when people start to believe in you, you are gradually able to attract collectors and get more good artists involved. Accordingly at the time I represented artists from the area, mostly young artists from different fields like painting, sculpture, installation and mixed media. But I was already interested in digital art when I met the artist Laurence Gartel in Miami in 1987. He was teaching computer graphics at the School of Visual Arts in New York. I was fascinated by his color prints created on the Amiga Commodore and bought one right away. I started to exhibit some of his art, as well as those of other artists in the field of digital art who I discovered. Many of them were not well known. There was for example Wolfgang Kiwus, who worked with plotter drawings for quite some time. Many of these artists didn’t really have a career, which is not surprising considering that it was a difficult market at the time.

In the 1990s I met Manfred Mohr and other pioneers at SIGGRAPH in the US and Ars Electronica in Linz (Austria), which were the two main events where you could meet some of the leading artists working with digital art. Manfred’s approach, as being very conceptual, just complimentary to the pop-art oriented Laurence Gartel, fascinated me from the beginning. Through Manfred and attending these events I got to meet further artists working with digital media. Back then I had the only gallery presenting digital art as a new genre, so they were happy to collaborate.

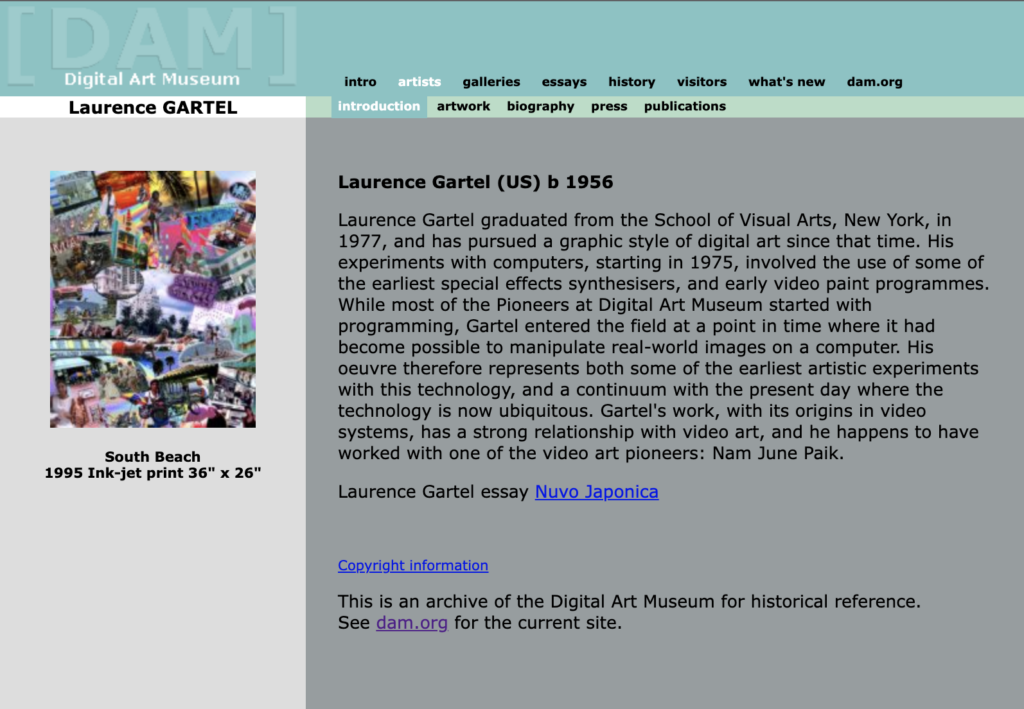

These were, among others, Yoichiro Kawaguchi, Yoshi Abe, Jean-Pierre Hébert, Roman Verostko and later Casey Reas. Many of these artists were later included in the first version of the online Digital Art Museum, which I started in 1998. Beside all that the backbone of my gallery, what kept it going financially, was still painting and sculpture as a larger part of the program. But I worked on it.

“The idea of the online museum came about because I realized, by talking to professionals of the art world, that there was a lack of understanding on the history and importance of this genre.”

In the late 1990s, you curated a solo show of Laurence Gartel that went to several cities in Germany. Was digital art getting more recognition then?

I curated the solo exhibition for Laurence Gartel titled “20 Years of Computer Art” in 1997. It was sponsored by Philip Morris and shown in Munich, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Berlin. My connection with this company came from working as an art consultant. They commissioned three pieces from Gartel, who at the time had been working for two decades in digital art. He had started in the 1970s, coming from photography and video. Despite succeeding in getting commissions from the likes of Philip Morris, Commerzbank (a major German bank) or VISA Germany and other companies, the interest that companies had in digital art was mainly about positioning themselves in connection to a form of avant garde art that spoke to a younger generation and was in line with the growing visibility of digital media. So this didn’t mean yet that there was a widespread interest or that the art market was opening up. There were some sales, but compared to the market for traditional media, it was really, really tiny.

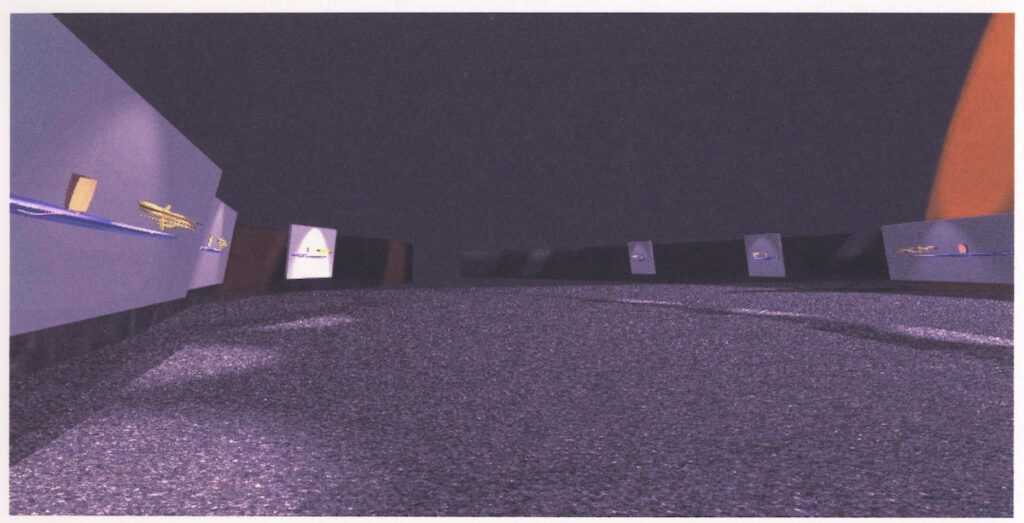

Also at this time you started working on the concept of a Digital Art Museum, which was supposed to take place in what we now call a metaverse. Why did you decide so early to create an online museum and at the same time to move away from a simulated 3d space?

The idea of the online museum came about because I realized, by talking to professionals of the art world, that there was a lack of understanding on the history and importance of this genre. As an example, I was a member of the Friends of the Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK) in Frankfurt, which had recently opened, and I met the director, Jean-Christophe Ammann, with the purpose of introducing digital art to him. He totally rejected it. He didn’t want anything to do with computers and art. And that happened with many others. I was still very excited and at the same time naïve, so I thought they would be interested too, but no. This made me realize that none of them had a clue about the history of digital art. They didn’t know about the pioneers from the 1960s, the different forms of artistic creation or the conceptual basis of working with algorithms. Accordingly, the idea of an online digital art museum seemed to make sense to communicate this history.

I got in touch with the director of the Institut für Neue Medien in Frankfurt and pitched him the idea. He loved it and suggested an architect and designer, Rupert Kiefl, who could help to develop an initial concept of the online museum. Kiefl developed a virtual space using VRML, that would host the artworks as placed on the virtual walls. Something you find now all over in the metaverse. But here we were at the end of the 1990s, and the internet was still really slow and the resolution of the images was too low in connection with the virtual environment that needed to be loaded as well. It was an interesting idea, but on the one hand it didn’t provide a good experience, and on the other I felt that it didn’t make sense conceptually. Why have walls, a ceiling, and a floor in the virtual world? You don’t need that. It felt kitschy for me to try to repeat the experience you have when you go into a museum or a gallery. So that’s why I ended up with a more basic platform.

I can understand now, as processing times and image resolution capabilities have improved enormously, that a 3D environment can provide an engaging experience, and that, for instance, it can be an advantage to see the real scale of the artworks. But still, I think that there could be much more interesting concepts to present art in the metaverse.

The Digital Art Museum (DAM) went online in 2000. Back then I was in London, running the Colville Place Gallery with a partner, the web-designer Keith Watson. We got in touch with Dr. Mike King, an artist and academic from Guildhall University London, who liked the idea of the museum and took part in developing the structure and the contents of the initial website. The site was designed and developed by Persistent Objects Ltd. The first DAM Museum was funded by a grant of the AHRB and built over a period of one year.

Colville Place was the first art gallery at the time fully devoted to digital art. You were a partner in it from 1999 to 2002. Can you tell me about this period in your career?

I joined Colville Place Gallery, which was started in 1997 in London, on invitation by Keith Watson. He had been running the gallery with another partner, who had quit at the time. I decided to join him. I kept the gallery in Wiesbaden, traveling back and forth between Wiesbaden and London. I actually slept in the office of the gallery in London, because it was too expensive to rent an apartment. We didn’t make any money, and we had to put money into the gallery in London every month to keep it afloat. So it was a challenging, but also exciting experience. We hoped it would take off, but in the end it didn’t. Back then I was making money basically from the more traditional art I sold in the gallery at Wiesbaden. After three years, I had to realize that the London gallery was not going to succeed, so I decided to leave it. Keith kept it going for another 2 years.

“Usually it can take about six or seven years for a gallery to turn a profit, so you need to invest a lot of money, hoping it will work out in the end.”

Usually it can take about six or seven years for a gallery to turn a profit, so you need to invest a lot of money, hoping it will work out in the end. There are exceptions, and of course it is different depending on your background, your connections, the money you can invest, and so on. When you start from scratch, like me, and deal with a type of art that is not well known or understood, it is particularly difficult. You have to be really persistent. And of course, you need to have a vision which hopefully turns out to be successful. Keep in mind that, just to run the gallery, with some staff, rent, transportation, and so on, you need at least around 10,000 or 15,000 € per month. So even if you are selling from your shows, which will usually involve a young, lesser known artist selling at low prices, you will most likely be paying off your expenses. Many galleries last for only a few years, even if they start with a considerable investment. I remember, for instance, Carroll/Fletcher in London: they had an impressive space in the city center and developed a great program with very well known artists in this genre. They must have spent a fortune. And after five years, they just disappeared. I was lucky that, despite having invested so much in the London and Wiesbaden galleries, I could recover over the years. But when I moved to Berlin and opened the DAM gallery, in the beginning I had to be careful about costs and I couldn’t attend many art fairs.

While you were running the Colville Place gallery alongside Keith Watson, there was an unprecedented interest in digital art, and more specifically Internet art, partly due to the dot com bubble and the new Millennium. What was your perception of the London art scene and the market at the time?

I remember very clearly being at the gallery in London and talking with artists who were doing net art, and I was so excited about this field, because there were such fantastic things happening, but there was not much understanding about the web, particularly in the art world.

Also, the problem was that there was nothing to sell! Everything was online and there seemed to be no way to sell it. Artists like JODI, who were creating purely avant garde pieces that were among the first to address Internet culture and an aesthetic of web-based art, found it difficult to sell any of their artworks. Most artists were just excited to get recognition for what they were doing. You could reach your public directly, without a curator or gallerist, that seemed to be the future.

“In the early 2000s, there was the feeling that digital art was finally being recognized in the art world, but as it turned out this surge of interest was short-lived.”

In London there wasn’t that much of a dot com bubble, at least I don’t remember that it directly affected business as it did in the US. But there was, as you say, unprecedented attention to digital art. TATE was commissioning Internet projects back then, and in New York the Guggenheim was acquiring net art pieces for their collection. There were also many exhibitions taking place in museums and art centers, with curators like Steve Dietz and Christiane Paul who was involved in the famous Whitney show BitStreams from 2001. Net art communities like Rhizome existed since 1996 and a magazine devoted to digital culture called ArtByte around 2000, which sadly only lasted a few years. There was the feeling that digital art was finally being recognized in the art world, but as it turned out this surge of interest was short-lived. Still it resulted in another gallery dedicated to that field: bitforms gallery in New York opened in 2001.

In 2003 you opened the DAM Gallery in Berlin, after closing the galleries in London and Wiesbaden. Why did you choose Berlin? Which were your expectations about the art market there?

I was still very excited and convinced that digital art was going to be widely recognized. And I realized that in London the market was still comparatively conservative, and while there was a lot of money around, collectors were mainly focusing on the big names of contemporary art. So I started to think where in Europe could I set up such a gallery? In Italy there was not much happening regarding digital art at the time. In France, the Paris art market also seemed quite conservative. And Berlin was this large newborn city with a lot of potential and a large vacuum. You did not need to invest much to create something because the costs were comparatively low and, as I felt it, people were coming there to discover something new in the art world. More than any other city in Europe, Berlin was representative of very contemporary new movements and art. The other side of it, of course, and I learnt this very quickly, as every other gallery told me as well, was that there was no money in Berlin. There were hardly any collectors, and so very little of my sales were actually happening in Berlin. But the art scene was and still is exciting. There were so many good things happening.

I opened the gallery in Mitte, which was the location you had to go in the former East part of town, where all the galleries were, among them many of the most famous ones. Every foreigner who came to Berlin went to Mitte to visit the galleries. So I had a first space there, and when I rented it from the owners, they said they already had two galleries in there, each one survived only one and a half years. So of course, there was a lot of fluctuation. And they were really happy when they saw that I persisted. Still, in the first 10 years in Berlin, I made it was still difficult for the gallery. I survived by combining the gallery with my work as an art consultant.

You have had different locations in Berlin, and a second gallery in Cologne, followed by another one in Frankfurt. What motivated these different changes? And what did you see each time in the market as a result?

As I mentioned, there really wasn’t a market in Berlin, so I looked for a second location. I had a gallery in Cologne for two years, the most established art market in Germany. But the gallery community was not so open for newcomers. I couldn’t even announce my shows in the gallery associations’ agenda, even though you had to pay for it. But this is a different story about the gallery scene. Nevertheless I met some interesting people, made some new customers and kept some friends among the galleries there as well.

Some years later, I had another second location in Frankfurt, which seemed a good choice because I already knew several collectors there and I originally came from that area. But it turned out that these collectors would rather go see my shows in Berlin than to visit the gallery in Frankfurt, so after one year I closed that space again.

I have moved a few times with the gallery in Berlin with the intention of providing a better location for the artists. For a long time Berlin Mitte had been the place to be for galleries with a high concentration. But that area has become quite expensive and mostly been taken over by large chains. In recent years, more and more galleries have moved to the old West-Berlin Charlottenburg, which has a lively well developed infrastructure. We have taken the chance during lockdown to find a nice shop location there, which allows us as well to organize different kinds of events and concerts for the local community. Right between Charlottenburger Schloss and a lake with a park on the other side. Our neighbor is a gallery as well.

In 2005, shortly after you opened the gallery in Berlin, you created the d.velop digital art award ddaa, a lifetime award for major pioneers of the genre. Can you tell me how it came about and its development?

I was approached by the company d.velop AG that asked me to create an award for digital art in 2004, which was a great project for me as it was well funded and helped to expand the gallery while building a reputation for the digital arts. At the same time, Wulf Herzogenrath, director of Kunsthalle Bremen, who was an opinion leader for video art back then, recognized the potential of digital art and offered to host the exhibition for the lifetime award winner. He was introduced to the whole field by the pioneer Frieder Nake, who lived in Bremen as well. So it was a lucky coincidence that I could put together these sponsors and launch an award consisting of a prize of 20,000 €, an exhibition at Kunsthalle Bremen and a catalog. The award took place every two years until 2011, recognizing the work of pioneers Vera Molnar, Manfred Mohr, Norman White, and Lynn Hershman Leeson. The award was discontinued in 2012 due to the end of the sponsorship, but I have plans to relaunch it this year as the DAM DIGITAL ART AWARD, in a different format.

Also at this time you stared the Digital Art at Sony Center program in Berlin, a unique public showcase of digital art. How did it come about, and how has it been developed?

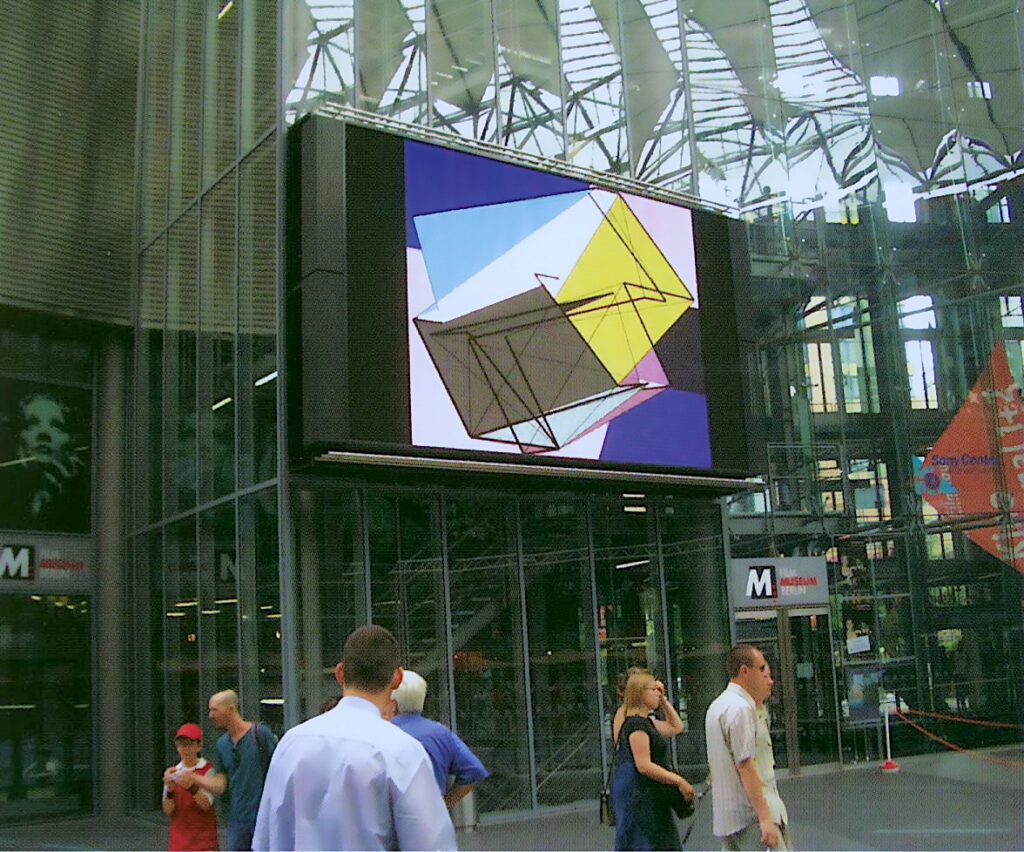

The public video screen in the courtyard of the Sony Center in the middle of Berlin pursued from the beginning a mixed strategy of advertisement, PR, and other content. Since 18 years we collaborate with the owner of the screen and provide every 6 months a new program that usually showcases the work of 3 artists, each one exhibiting one artwork. This program is shown 5 to 6 times every day. In this program, we have worked with external curators or introduced new artists ourselves. From what I know, this might be the only public screen that shows digital art continuously over such along period of time.

You wrote a book about digital art that was published in 2009 and widely distributed. Can you tell me why you decided to write this book and what impact did it have on popularizing digital art?

When I had my gallery in Cologne, I went to an opening in another gallery and there I met the chief editor of Tandem Verlag, a publisher and distributor of books and electronic media, which also sold publications with CDs and DVDs. They had started a line of small books about art, they had just published one about street art and were interested in including one about digital art. The challenge was that I had to write it in three months, following a fixed structure. The book, titled “Digital Art” came out and was translated into six languages and sold nearly 33,000 copies. They liked it so much that they offered me to produce a coffee table version with a DVD, which came out in 2010 and sold nearly 7,000 copies. It was the first book in Germany that gave an introduction to this field. For this version I had more time and brought in some guest authors to contribute small sections to the main text. The book was quite popular, and I think it did contribute to bringing some awareness about digital art, although of course there are more influential books, like Christiane Paul’s Digital Art from 2003.

“I love what Niio is doing. It allows you to really get involved without having to pay a large amount of money to own a piece. And you have the opportunity to experience a lot of different art.”

And what is your perspective on the popularity of digital art nowadays, is this the time when digital art will finally be integrated into the contemporary art field?

Yes, I think so. To put it in perspective, there has been video art in the art market since the 1970s. Since then, it has been established on the art market on an international scale. But if you look at the actual market as such, an enormous amount of it is still painting, according to statistics a major part of the artworks sold are still paintings. So, video art amounts to a comparatively small percentage of the art market, even as nobody questions its importance and relevance. I think something similar will happen with digital art, although the NFT market has brought widespread attention to it, and the younger generation is much more connected to this kind of world. Nowadays, most people, and particularly young collectors, are finding it natural to have art on their screens. They live with it, they experience it on a daily basis.

In that sense, now that you have started a collaboration with Niio and also have experience with other online platforms, what do you think about art streaming?

I love what Niio is doing. Because, first of all, it allows you to really get involved without having to pay a large amount of money to own a piece. And you have the opportunity to experience a lot of different art. This is particularly interesting, because I tell everybody who comes in for the first time into the gallery and is interested in digital art, and likes something, then I say, okay, wait a moment, come back in a week or two, or a month and look at it again, let it work on you, get familiar with it. Because that will change your views.

And that’s what Niio allows you to do, you can experience a lot of different kinds of art. And some of it you will be totally excited in the first five minutes. And after an hour, you might say, oh, well, okay, let’s go for the next one. While other artworks, you will want to live with them, to see them every morning.

I also like that it offers a way for artists to make some additional money without it interfering with their regular market where they sell or do unique one certifications or something like that. So I’m totally sure that this will gain momentum and that it will be interesting for people and companies as well as a means to gain access and understanding of digital art. And then they can check out DAM!