Niio Editorial

This year has been full of excitement, marked by both challenges and remarkable achievements. We have welcomed new partnerships and expanded our team, working hard to achieve new milestones in our commitment to bring digital art to everyone, everywhere. We are thankful for the continued trust of our partners and investors, and look forward to exciting new projects in 2025.

In this article, we offer a brief reflection on what 2024 has been for us at Niio, along with a heartfelt thank you to all the artists, galleries, collectors, curators, and art enthusiasts who share and celebrate art with us.

Our latest showreel video offers a glimpse into the many ways Niio works to facilitate the experience and appreciation of digital art.

Artcasts: your space to discover art

Artcast are our curated selections of artworks that any Niio user can play on the screen of their choice, turning it into a digital art canvas. We consider artcasts a space in which art lovers and collectors can discover new artworks and experience them as they would in an art exhibition: on a dedicated screen. Our curated art program welcomes the latest creations by the artists on our platform, enabling them to share both works in progress and finalized series, available for sale on Niio and through their galleries. This year, we are proud to have launched 23 artcasts featuring the work of outstanding artists, as well as collaborations with galleries, art centers, and universities.

Here are some of our favorite artcasts this year, but you can find many more by browsing the Discover area in our app.

Marina Zurkow. Elixir I, 2009

WITCHCRAFT

We celebrated Halloween with this artcast that showcases the work of women artists who delve into themes and realms of knowledge historically associated with witchcraft accusations, such as natural sciences, the human body, the nature of reality, and the critique of established gender roles. In their art, traditional symbols of witchcraft—like potions, enigmatic transformations, dark forests, full moons, and magical incantations—transcend their historical connotations to become vibrant expressions of these artists’ creativity and insight.

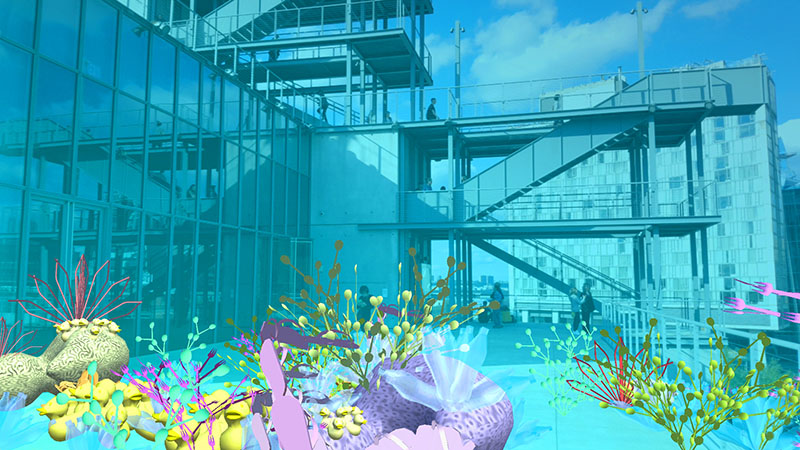

Tamiko Thiel. Unexpected Growth (Whitney Museum Walk1), 2018

DIGITAL BY NATURE

We celebrated our ongoing collaboration with DAM Projects by hosting this artcast curated by Wolf Lieser in which the artworks of four artists and artist duos represented by DAM Projects bring us views of nature mediated by technology. Driessen and Verstappen’s visualization of the pace of nature dialogues with boredomresearch’s approach to nature as a system, while Eelco Brand applies a painstaking recreation of natural environments as fictional compositions and Tamiko Thiel plays with the seductive beauty of nature to bring forth concerns about our role in the pollution of the oceans.

“I love what Niio is doing. It allows you to really get involved without having to pay a large amount of money to own a piece. And you have the opportunity to experience a lot of different art.”

Wolf Lieser

ZEITGUISED. Gem Forest, 2024

ZEITGUISED: HYPERREAL

We recently renewed our collaboration with ZEITGUISED, the studio founded in 2001 by Henrik Mauler and Jamie Raap, that has been a long time collaborator of Niio. ZEITGUISED has crafted a distinctive style of animation that serves as their hallmark, evident both in the elements they depict and in the flowing, organic movements of their characters, whether floating gemstones, a pink moon, phantasmagoric garments, or abstract, liquid forms. The artcast Hyperreal presents a selection of ZEITGUISED’s short films, progressively traversing the boundary between photorealism and abstraction. This collection features newly reimagined versions of select works, produced exclusively for Niio.

Chun Hua Catherine Dong. Meet Me Halfway – part 1, 2021

Artists: the core of creativity

Niio was founded with a core mission: to support and empower artists. Our platform provides them with a secure and efficient way to manage and showcase their portfolios, enabling seamless sharing with collectors, galleries, institutions, and art enthusiasts. Beyond this, we actively recommend their works to clients in our Art in Public program, feature their latest creations through our Curated Art initiatives, and build deeper connections by sharing their stories in the conversations published in our Editorial section. This year, we’ve launched more than 20 solo artcasts and a dozen group shows, as well as highlighted 41 selected artworks in our Artwork of the Week showcase on social media. We’ve also introduced the Artist of the Month post in our social media accounts, aiming to highlight the career of some of the most outstanding artists in our platform. In addition to this, we’ve published 15 interviews with the artists in our curated program, as part of our commitment to let our audience know the creators behind the art.

These are some of the artists we’ve showcased this year. We’d love to include them all here, but you can find them in our Discovery area.

MOONWALKER

Over the last two decades, the Brussels-based Colombian artist has carried out a consistent body of work in the form of interactive audiovisual installations and lThe creative duo Moonwalker (Dany Vo and Vy Vo) has its roots in the worlds of graphic design and illustration, where they honed their skills in creating mesmerizing artistic compositions exploring nature and fashion.

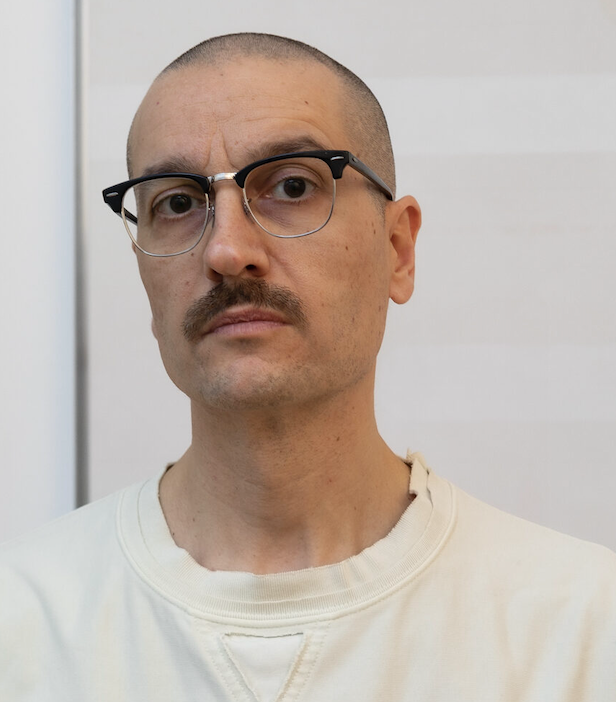

RONEN TANCHUM

A contemporary artist, developer and an interaction designer, Ronen Tanchum has developed a body of work that explores the representation of natural phenomena and our perception of reality as it is mediated by the entertainment industry and digital media.

POLINA BULGAKOVA

Polina Bulgakova is a digital 3D artist who has developed her practice since 2020. Working in the “surrealistic realism” style, Polina crafts visual narratives that challenge the constraints of real-world physics, inviting audiences to think beyond conventional limits and embrace the possibility that anything is achievable

DEV HARLAN

Dev Harlan is a New York-based artist whose work in sculpture, installation, and digital media explores the interplay between technology, nature, and the impact of human activity on our planet.

TAHN

Tahn (Taeyoung Ahn, born in South Korea, 1967) is a multifaceted media artist, technologist, writer, and art educator with an extensive career that spans multiple disciplines.

Public showcases: where art shines

Working closely with leading contemporary art galleries and establishing partnerships with premium business and hospitality venues is central to our goal of bringing exceptional video and digital art to top-tier spaces and seamlessly incorporating art into daily life. We are proud to have developed strong ties with leading digital art galleries bitforms (New York), Galerie Charlot (Paris), and DAM Projects (Berlin), as well as with many other professional art galleries, and to provide curated art selections to some of the most prestigious brands and properties, such as Conrad Hotels & Resorts, Tempo by Hilton, The Mondrian Hotel Seoul Itaewon, Aloft Hotels, and many others.

Below are some highlights of a very busy year with wonderful collaborations and promising partnerships. You can find more about our activities on our LinkedIn and Instagram accounts.

NIIO x SMTH: THE WORLD(S) WE WANT

Niio partnered with SMTH in an open call for art students that brought the work of five selected artists to more than 30 screens in several shopping malls located in major cities in Spain. We were grateful to count on the collaboration of artist and researcher Snow Yunxue Fu and the jury members Wolf Lieser, founder of DAM Projects, Valentina Peri, independent curator, and the artist Solimán López. The five winning artists, Bruno Tripodi, Cruda Collective, Rolin Yuxing Dai, Cosette Reyes, and Katsuki Nogami, saw their work displayed in spectacularly large screens in the public space. Crucial to the success of the open call was the generous support of LED&GO, as well as Laba Valencia, ESDi, New York University, Université Paris 8, BAU, and Elisava, among other schools and universities.

DIGITAL ART WEEK LONDON

Niio’s co-founder and CEO Rob Anders participated, alongside Steve Sacks, founder and owner of bitforms gallery (New York), in a fireside chat hosted by Ideaworks during the Digital Art Week in London. This highly successful event featured a pop-up exhibition of a curated selection of artworks by Refik Anadol, Quayola, Marina Zurkow, Claudia Hart, and Jonathan Monaghan, all of the represented by bitforms.

TALKING GALLERIES

Our Senior Curator Pau Waelder was invited to participate in this year’s edition of Talking Galleries Symposium in Barcelona, making this the third time he is featured in the program of this well-known event. Waelder moderated a panel talk on “Creating and Selling Digital Art in the Age of AI” with the speakers Anne Schwanz, from Office Impart gallery (Berlin), and the artists Carlo Zanni (Milano) and Daniel Canogar (Madrid).

ART BASEL WEEK, PARIS

Our co-founder and CEO Rob Anders gave an interesting talk about collecting digital art to a professional audience during the Art Basel week in Paris. The talk was hosted by DANAE and lead by curator Rachel Chicheportiche. This event was also a wonderful occasion to showcase the work of Quayola, Yoshi Sodeoka, Ronen Tanchum, and Jonathan Monaghan.

ANTHROPOSCENES

A digital art program taking place during the whole year at the facade of Lo Pati Centre d’Art de les Terres de l’Ebre (Amposta, Spain) has been a wonderful opportunity to showcase the work of six talented artists whose work is available on Niio. Marina Zurkow, Claudia Larcher, Diane Drubay, Kelly Richardson, Yuge Zhou and Theresa Schubert have produced audiovisual artworks that offer us, from different perspectives, scenes of life in the Anthropocene, particularly those environments and systems that we ignore but that play a determining role in life on Earth. From the ocean floor to the mines from which the materials that enable our digital life are extracted, from glaciers to atmospheric phenomena, from forest fires to crowded cities, these works lead us to reflect on our planet, the world in which we want to live and what we will leave to the next generations.

Articles: art in theory, art in conversation

This section forms a cornerstone of Niio’s work, offering a platform for documentation, reflection, and dialogue with artists, gallerists, and art professionals, while also serving as a hub for insights and discussions on key topics in contemporary art. This year, we learned a lot about the artist’s creative processes, and particularly the expectations of young artists who are still in the final phase of their studies.

Read some of our most commented articles this year and find many more by browsing our Editorial section.

📝 Paolo Cirio’s Climate Tribunal: Climate Justice, Art, and Activism

Review of the book Climate Tribunal by artist and activist Paolo Cirio addressing the role of the fossil fuel industry in the climate crisis and its responsibility for its disastrous effects..

📝 Jaime de los Ríos: Sculpting Infinity

Interview with Jaime de los Rios, visual artist and programmer whose work blends contemporary art, science and technology, creating immersive environments and generative works, often in collaboration with other artists, scientists and engineers.

📝 Franz Rosati: The Collapse of Truth

Artist Franz Rosati discusses his latest series DATALAKE: GROUNDTRUTH (2024) in which he worked with AI models to generate mesmerizingly fluid landscapes that evoke chaos and disaster, but also regeneration and impermanence.

📝 Niio x SMTH: The World(s) We Want

A series of interviews with the winning artists of the Open Call for Art Students revealed the creative processes and expectations of young artists with a bright future ahead: Katsuki Nogami, Rolin Dai, Cruda Collective, Bruno Tripodi, and Cosette Reyes.

This is just a glimpse of what Niio has been in 2024. We look forward to doing much more in 2025, and we’d love to share our journey with you!