Ben Fino-Radin

Artists have always reached for the tools, materials, and technologies of their time. The 20th century in particular has witnessed the greatest explosion of new materials for artistic experimentation.

Celluloid, analog video, early mainframe computers, networks, robotics, the personal computer, the world wide web – you name it. Artists created works with these tools as soon as they could get their hands on them – be it by sneaking into a video post-production house after hours, or by private corporations sharing the wealth through artists residencies (for instance, Bell Labs). The year I am writing this, 2016, marks the 50th anniversary of Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), a Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Kluver founded organization established to develop collaborations between artists and engineers.

While fifty years is young for an artistic medium, during that time, we have seen technologies come and go making artworks created with these tools and formats oftentimes inaccessible, obsolete and impossible to recover all with drastic stakes. We suddenly have an entire generation of artistic creation – cultural heritage and artifacts – that are at risk of simply disappearing. While all works of art can fall apart eventually if not cared for, even a sculpture made out of concrete, the materials of the 20th and 21st centuries do so at an alarming rate, and are at great risk of disappearing long before institutions deem it worthy of collecting and preserving (if ever).

Thankfully there is at least one preventative measure that can be employed: digitization. It is a well established fact that there are no analog media carriers that will last forever – by digitizing analog media, we can ensure that the contents can be losslessly preserved and migrated into the future. However, digital files can also fall apart – become corrupted, obsolete, lost, deleted. To combat that, an entire profession has evolved, devoted solely to digital preservation. Museums, have experts (myself included) dedicated to preservation.

- What does it mean to “preserve” something digital?

- When you “preserve” a digital artwork, what are you actually preserving?

First and foremost, you are preserving the digital files (videos, sound files, still images, executable software) that make up the artwork and that are necessary to exhibit and/or view the artwork. These files contain the data: zeroes and ones that make up bits and bytes. Preserving these zeroes and ones perfectly (and being able to prove and demonstrate that one has done so) is paramount when talking about a work of art. No matter what storage medium these files are copied to, we must be able to prove that the same file, bit for bit, every zero and every one has been accounted for. This is how we can prove and validate the authenticity of digital art.

Preserving these bits and bytes however is just the first step – just because we have perfectly stored a file, doesn’t mean that in the future it will be understandable. Therefore, we need to record data about the data – metadata – about what these files are, what they are supposed to look like, and what purpose they serve within the larger context of the artwork. For instance, are these video files part of the artwork itself, and they meant to be projected in the gallery, or are they videos documenting the exhibition of the work? Without the preservation of this contextual information, the files are useless.

The last piece of the puzzle is storage – we need to put all of this information somewhere safe. Unfortunately digital storage is by its very nature fallible – just as there is no archival or permanent analog storage medium (safe for film, when properly cared for) – there is no permanent or archival form of digital storage. Thankfully we can design around this problem. First and foremost, we can build storage devices that have built in redundancy and safety measures, including the ability to identify problems. Secondly, we need to store multiple complete copies of all of this data and metadata in multiple locations. This protects us from natural disaster, or complete failure of the digital storage device.

In theory, all of these principles are quite simple. The problem is that in practice they are quite hard. People have limited time, money, and expertise, and unfortunately, uploading assets and artwork to a cloud storage platform meant for regular everyday use simply isn’t a viable digital art preservation plan. Most artists have a hard enough time finding creative headspace with everything they are already juggling: paying the bills, running their studio, getting ready for the next exhibition, seeing their friend’s shows. Worrying about digital storage, checksum algorithms, growth projections, format obsolescence, viruses, natural disasters is yet another challenge that very seldom addressed.

This is where Niio comes in. I am collaborating with the team to not only make digital preservation accessible, but to also make it affordable and sustainable. Not just to artists, but to all of the various stakeholders in the art world: galleries, private collectors, institutions, you name it.

Read Our In Depth Q+A With Ben

Part 1: A Conversation With Ben Fino-Radin, Preservation Expert

Part 2: A Conversation With Ben Fino-Radin, Preservation Expert

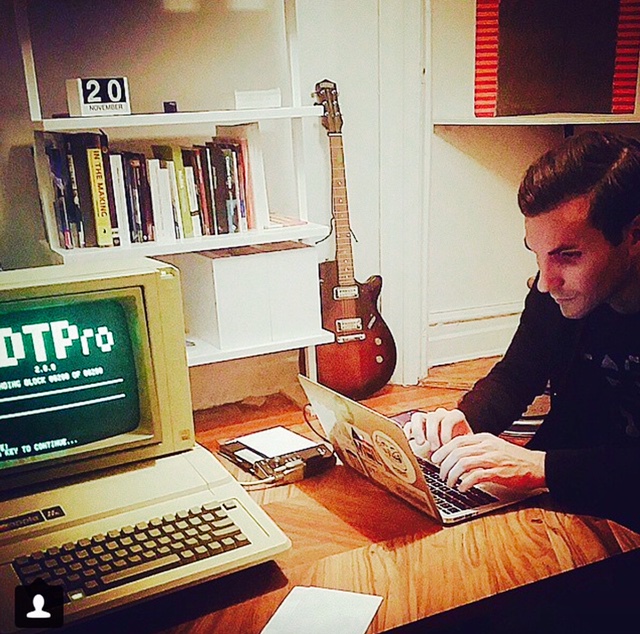

About Ben Fino-Radin

Ben is a NYC based media archaeologist, archivist and conservator of born-digital and computer based works of contemporary art. Until recently, he was the Associate Media Conservator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) where he developed strategies and policies that contributed to the preservation of the museum’s digital collections. Today, he is the founder of Small Data Industries, a consultancy providing services to support the collection, exhibition, preservation, and storage of digital and time-based media art. His clients include the Whitney Museum, The DIA Art Foundation, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the studios of Cory Arcangel.

Prior to MoMA, Ben worked as a Digital Conservator at Rhizome at the New Museum where he structured preservation and collecting practices for collections management, documentation, and preservation of born-digital works of art. As an Adjunct professor at NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation (MIAP) program, Ben taught a course on Digital Literacy designed to equip first year graduate students with fundamental technical skills for careers in digital archives as well as Handling Complex Media, a course designed to give second year graduate students practical skills for the identification, risk assessment, preservation and treatment of creative works that employ complex and inherently unstable digital materials.

Research interests include: digital preservation, digital cultural heritage, web based creative communities, computer history, information architecture, metadata and animated gifs.