Pau Waelder

The boom of the NFT market has decisively impacted the contemporary art market since, in 2021, Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction houses launched successful sales of digital artworks minted as NFT and offered in cryptocurrencies. A year later, despite the ups and downs of cryptocurrencies, the market for art in digital format with NFT certification continues to consolidate and progressively enters the scope of the most recognized galleries on the international contemporary art scene. In this context, it is worth asking: what do NFTs bring to art collecting? What trends can be traced in the future of the contemporary art market?

Invited by Art Palma Contemporani, the contemporary art galleries association in Palma, I curated a panel talk on September 16th, in which several experts presented their analysis of the current situation of the art market and NFTs and outlined future perspectives.

Valérie Hasson-Benillouche: “NFTs have brought a different kind of collector”

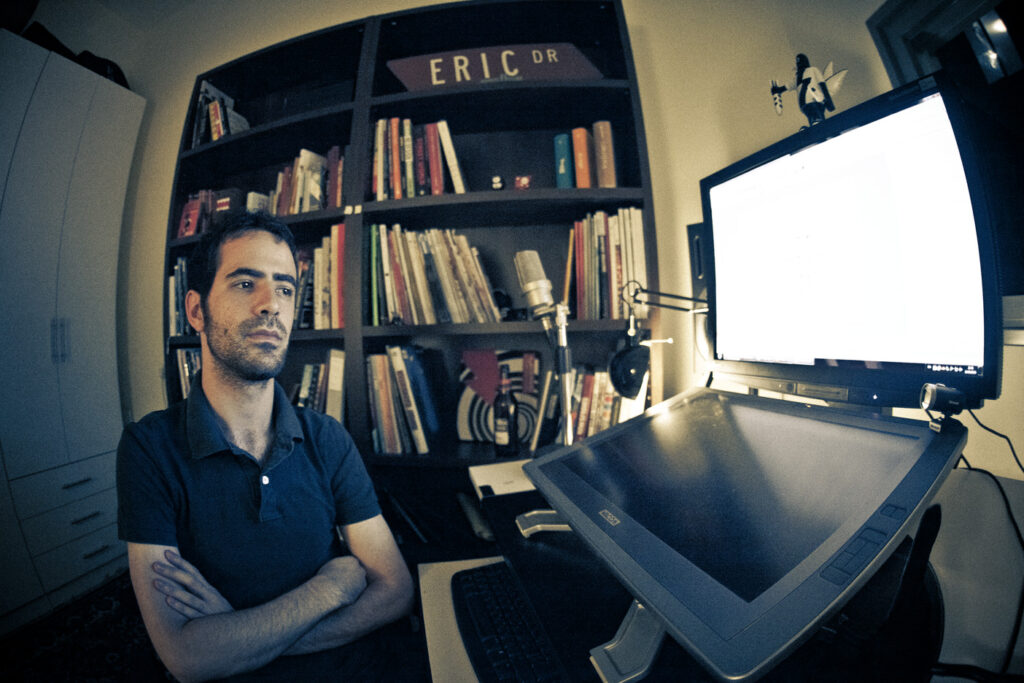

Valérie Hasson-Benillouche is the owner of Galerie Charlot. She opened the gallery in Paris in 2010 and then a second gallery in Tel Aviv in 2017. The gallery represents a wide range of artists working with digital art, such as Antoine Schmitt, Eduardo Kac, Lauren Moffatt, Laurent Mignonneau & Christa Sommerer, Louis-Paul Caron, Manfred Mohr, Nicolas Sassoon, Quayola, and Sabrina Ratté.

2022 is a key moment for your gallery entering the NFT market with the participation in the Unvirtual Art Fair in February and then the launch of your own NFT platform. What is the reception you are getting from your collectors regarding NFTs? Are NFTs helping you reach out to new collectors?

I opened the gallery about 10 years ago, so at this point my clients have already 10 years of experiences with digital art. NFT is one part of digital art, so they became very curious and came to me and said: “what is this new art?” I have to say that it took me a while to understand it, because it is not easy, and it was a new way of collecting. So it was important to me that the curiosity of clients could be a challenge to understand what is going on, and as artists always use new technology and create new artworks with all these different systems, we really had to get into it. My clients were curious but also worried: they had read the news about NFTs, and also some bad experiences, so their curiosity was balanced with some skepticism.

I decided to mix the groups of my collectors, because you always have different kinds of collectors: the ones who are buying because they really love art, the ones who buy art to challenge themselves and show their collection to other people, and some people who just want to please themselves, sometimes. All these people are wondering what is going on around this new NFT system, so I try to explain it to them and I take the time to organize talks with artists and curators, and different people who can explain to them what is a wallet, how to open it, something very simple. I think collectors really need to be guided through these basic steps.

“It is a different approach of living with the collection: you can see it anywhere, you can share it with your friends easily. This brings a different way of buying art.”

Valérie Hasson-Benillouche

NFTs have lighten up the field of digital art. I have been in this field for years, and I find it very interesting to see that who has started creating NFTs among the artists. Eduardo Kac, who is a very classical artist working with science, technology, and art, he got into NFT. Then many people got into NFTs without understanding everything, but they just loved it. The idea was to do something different, to jump into something different. So what we decided at the gallery was to get all these people informed about what are NFTs exactly.

NFTs have brought a different kind of collector. It’s a challenge, because it is a different currency, it’s immaterial, so it is a different philosophy of collecting, and it is also connected to the way that people are living. Certain people are moving a lot, traveling everywhere, but they like to have their collection with them. They like to share the collection, they like to show the collection. So it is a different approach of living with the collection: you can see it anywhere, you can share it with your friends easily. This brings a different way of buying art.

You have collaborated with luxury brands such as Hermés in several artistic projects. Do you see an interest from these brands in art NFTs?

I’ve been working with luxury brands for a couple of years, especially with Hermés, as well as Audemars Piguet, Shiseido, and many others. Luxury brands really love to work with art and artists, this has been so for a long time. Digital art is part of the way they work with artists. So the challenge is always for any kind of artworks to find in these luxury brands the right place between marketing and art. The balance is very difficult to find, and it is not easy for an artist to work with a luxury brand, so digital art was the place to be because these brands have to be on the edge of super top technology and new things happening, because clients always ask for new experiences. So digital art was something very normal to get into. Artists try to find their place, in an artistic way.

Luxury brands are very interested and they have already dived into NFT, but for the moment it is more in the marketing and publicity side than in the art side. I am sure it will change, but they have to find the right moment and the right artists.

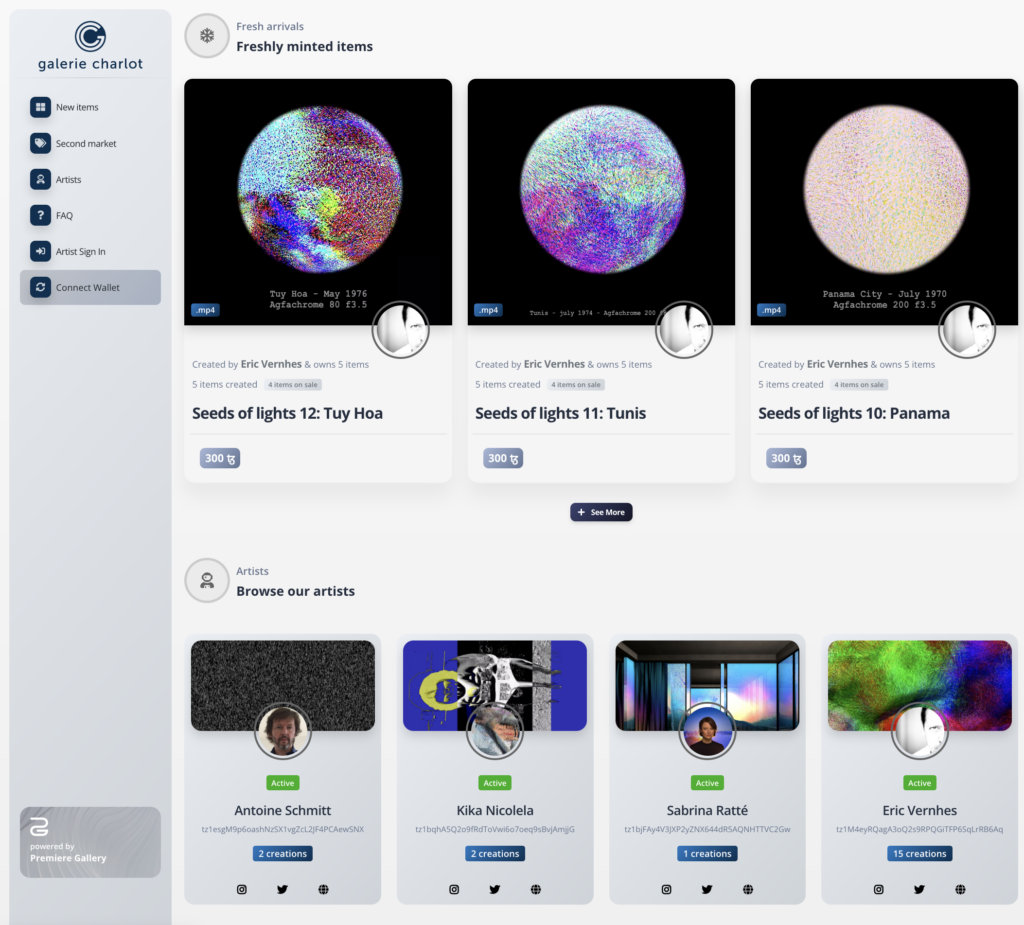

What type of work will we find in the new Galerie Charlot NFT marketplace?

We are still working on the marketplace, it will open on the 29th of October with several auctions. But the main thing is to curate digital art in NFT, because when you go to these different NFT marketplaces, you can find so many different kinds of images, I don’t say art, but image and video. It is not easy for a collector to go to these huge marketplaces because there is so much content which is not art. Other marketplaces like Feral File are very professional. The marketplace of the gallery will be a curation of the artists I’m working with, with special artworks that can be bought through auction or through the marketplace in Tezos.

We are not having a specific target on a specific art, but just to present art. I think artists love that: to be in small team, a very specific area of digital art, and it’s a big challenge because you have to bring a community: NFT is also a community of people and it is very important to be part of that community. I’m just listening to what is happening around and following the artists, who are adopting new technologies really fast and expressing their creativity in different ways. We are living in an incredible era, and we must be up to date, all the time.

Wolf Lieser: “what I really like about NFTs is the attention to generative art”

One of the most veteran gallerists in this field, Wolf Lieser opened in 1998 his first gallery devoted to digital art, Colville Place Gallery in London. That same year he created with Mike King the Digital Art Museum (DAM), one of the first online spaces devoted to the history of digital art. In 2003, he opened the DAM Gallery in Berlin, followed by spaces in Cologne (2010) and Frankfurt (2013).

In 2005 he created the DAM Digital Art Award to celebrate the work of digital art pioneers, and since 2006 he runs a public art program in a large screen at Postdamerplatz in Berlin. Recently rebranded DAM Projects, his gallery continues to support digital art. DAM represents some of the most celebrated digital artists, from pioneers to young creators such as Arno Beck, Eelco Brand, Vuk Cosic, Driessens & Verstappen, Herbert W. Franke, Carla Gannis, Jean-Pierre Hèbert, Eduardo Kac, Mario Klingemann, Manfred Mohr, Vera Molnar, Frieder Nake, Casey Reas, Anna Ridler, Sommerer & Mignonneau, Tamiko Thiel, Roman Verostko, and Addie Wagenknecht

Your decision to leave NFT sales directly to artists is quite unusual. What led you to it?

That was the result of many considerations. Of course, I got involved right away, because I’m working in this field since 30 years, so when this whole NFT thing happened, I was approached by different agencies which came up, and there was so much money around, and they wanted to sell and consult on NFTs, but I’m still a rather small gallery, so I have many activities going on. For me it was not a priority to get involved. It is important to understand that NFTs is a technology that certifies the ownership of digital art, but digital art I’m selling since 30 years. That has not changed: what we are selling here, which are NFTs, has been sold in a different way before. I sell software pieces since more than 25 years. So, I felt that it was not such an urge to get involved. I saw how Casey Reas made a fantastic career in this field, also Mario [Klingemann], and some of the artists have been extremely successful getting directly involved with NFTs because they are professionals in this field, they know enough about coding, they know enough about the technology, so they actually didn’t need me at all! There was no reason for me that I felt I needed to step in.

My position now, and that’s why I made a statement on the website, that I won’t be directly involved… of course I will make shows with artists who produce NFTs and we will sell the NFTs as well. But an aspect which I really like about this whole development, and it has affected my activity as well, is the attention to generative art. Generative art is an artwork which is software based and continuously changes on the screen, so it is an artwork that never repeats. That was a challenge to some people when they started to realize that. People are realizing now in a broader scale, especially younger people, what a fantastic field it is, how much it has to do with our culture of the 21st Century. This technology is affecting us every day, and there are very interesting and clever artists, like Mario and Casey, and others, who are picking that up and creating art with it, that makes us realize what kind of potential is in there.

“We need a world with much less material art, and much more generative”

Wolf Lieser

This whole NFT boom has brought about young collectors which have approached me because I represent the history of digital art since the 1960s, and I know all of the pioneers. The young collectors have realized there is a history of 60-70 years, and they have gotten into it. It is another approach, and as Valérie has said, and I love this approach, you have your collection with you, and you take it out and you put it on a screen. This kind of non-materiality is very important. We need a world with much less material art, and much more generative.

You have worked with the pioneers of digital art. Now that the NFT scene is looking for “OGs,” auction houses include artworks by these artists in their NFT sales, is this attention to the history of digital art misdirected, or do you see positive signs in it?

That is not so easy to answer, because in the last two years this field was so broad, and anybody who looked into digital art as form as NFT saw a lot of bad art. It was ridiculous. Specially, if you have experience, there were easy effects in JPEGs sold for enormous amounts, which if you were familiar with art you could say “how could you spend money on this?” But people did. And of course these people were not that much informed.

That is now getting to a normal level, and people are now starting to understand what other people have done before. If someone has created a concept, 30 years before and created it over a longer period, and suddenly a young artist comes around and does the same thing with a new technology, this is not very creative. You should know your history, you should know where it is all coming from. So it is helping to make history more broadly available, but it is like everything: you start to drink wine, you have to learn about wine. If you drink your first glass of wine you don’t understand the differences, and similarly in art you have to see a lot to understand what you are seeing. Then you develop your own taste and what you really love about it. Of course, the first painting I bought, I don’t want to look at it again.

In many of your exhibitions you have presented plotter drawings by pioneers and younger artists. Is it possible that now that we have so much digital, there is also a renewed value in having a physical artwork?

Just to clarify, pen plotters are drawing machines, they are not printers. The code is very different, they actually draw a line. At the beginning they were the only medium to present something on paper, but they faded out after 2000. They were not built anymore because inkjet printers were much cheaper. But in recent years, artists have become interested in plotter drawings again because of its tactile quality, the sensation of a real drawing on paper. And they have constructed their own pen plotters, so there is quite a scene that has developed around plotter drawings, which I address in the show that I have recently curated at DAM Projects, Remote Control. But these artists do NFTs as well, so it is one medium besides others. I think we will always have both.

In your long career, you have seen several moments in which digital seemed to be “coming of age.” Do you think this is the right time for digital art to finally be recognized as contemporary art?

It is happening, definitely. The early pioneers, such as Vera Molnar, an old lady of 98 years now, she is in the collections of MoMA, TATE, Pompidou, Victoria and Albert, many many institutions. So it is happening on this institutional level as well, although on a rather small scale. There are not very big collections yet. It’s a bit of a pity, because many of the good pieces are disappearing in private collections. But there is definitely much more attention to digital art than ever before.

Anna Carreras: “I create artworks that do not exist until someone buys them”

Anna Carreras is a creative coder and digital artist with two degrees in Engineering and Media Studies. She teaches coding in several design schools and has been awarded with the Cannes Golden Lion for Interactive Projects (2010) and Google DevArt (2014), among others. She has created interactive installations at Cosmocaixa, Expo Zaragoza, Forum Barcelona 2004, Sónar Innovation Challenge 2016, MIRA Visual Arts Festival, and the Mobile Art Week.

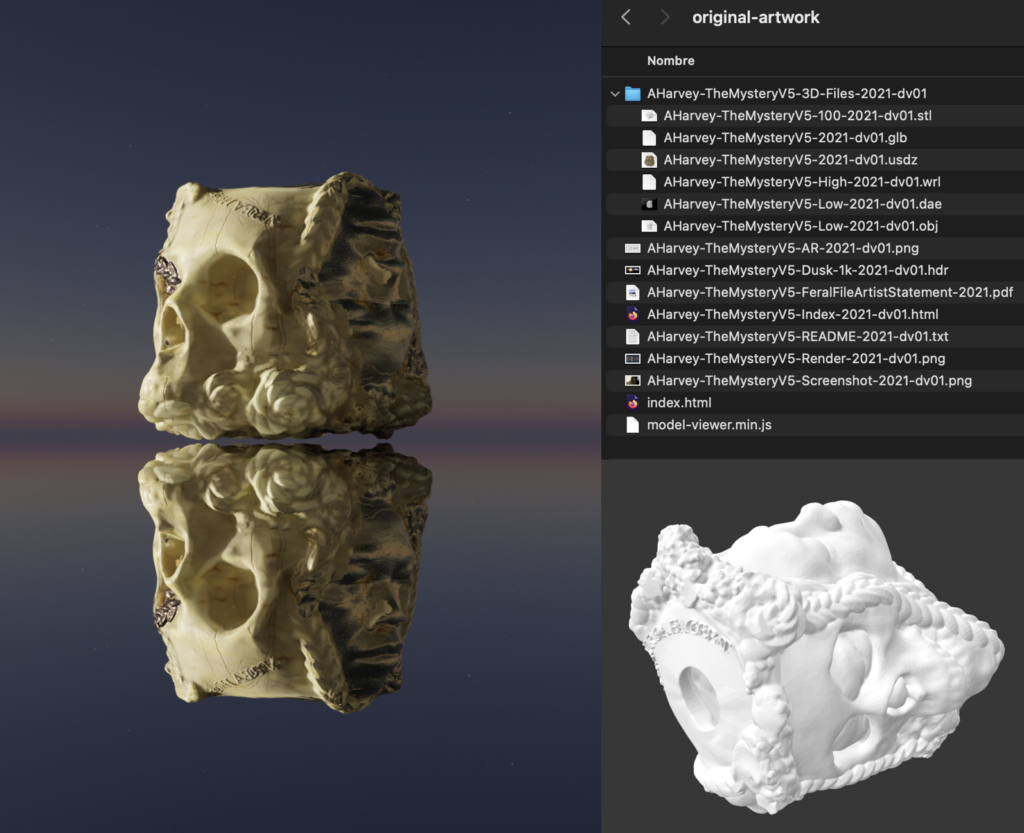

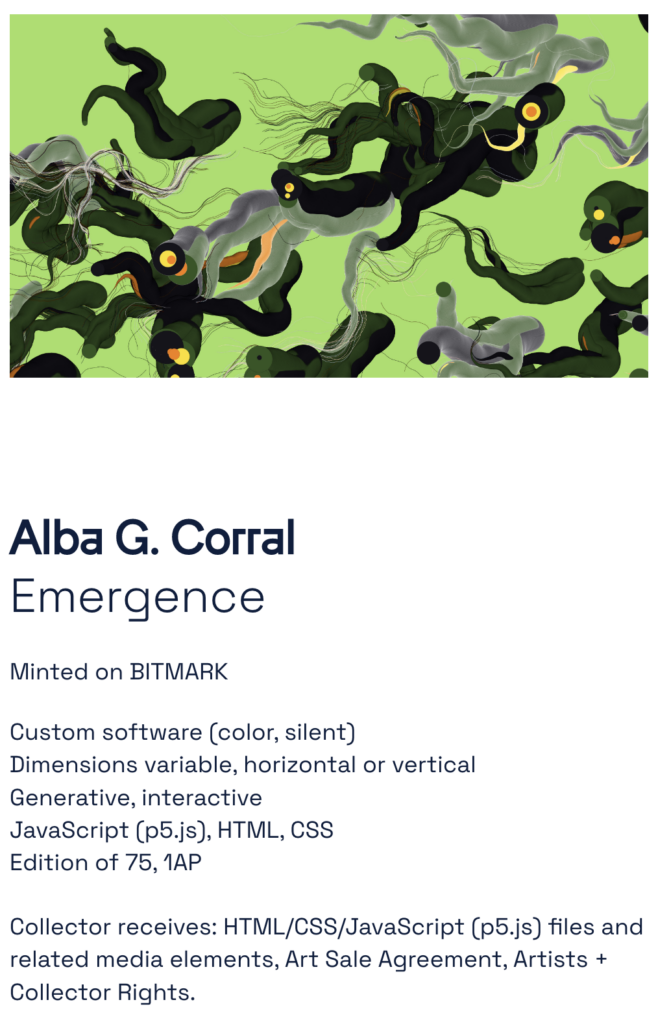

You have presented and sold your work in two very influential NFT platforms, Feral File and ArtBlocks. Can you explain the process of creation and sale in each of them?

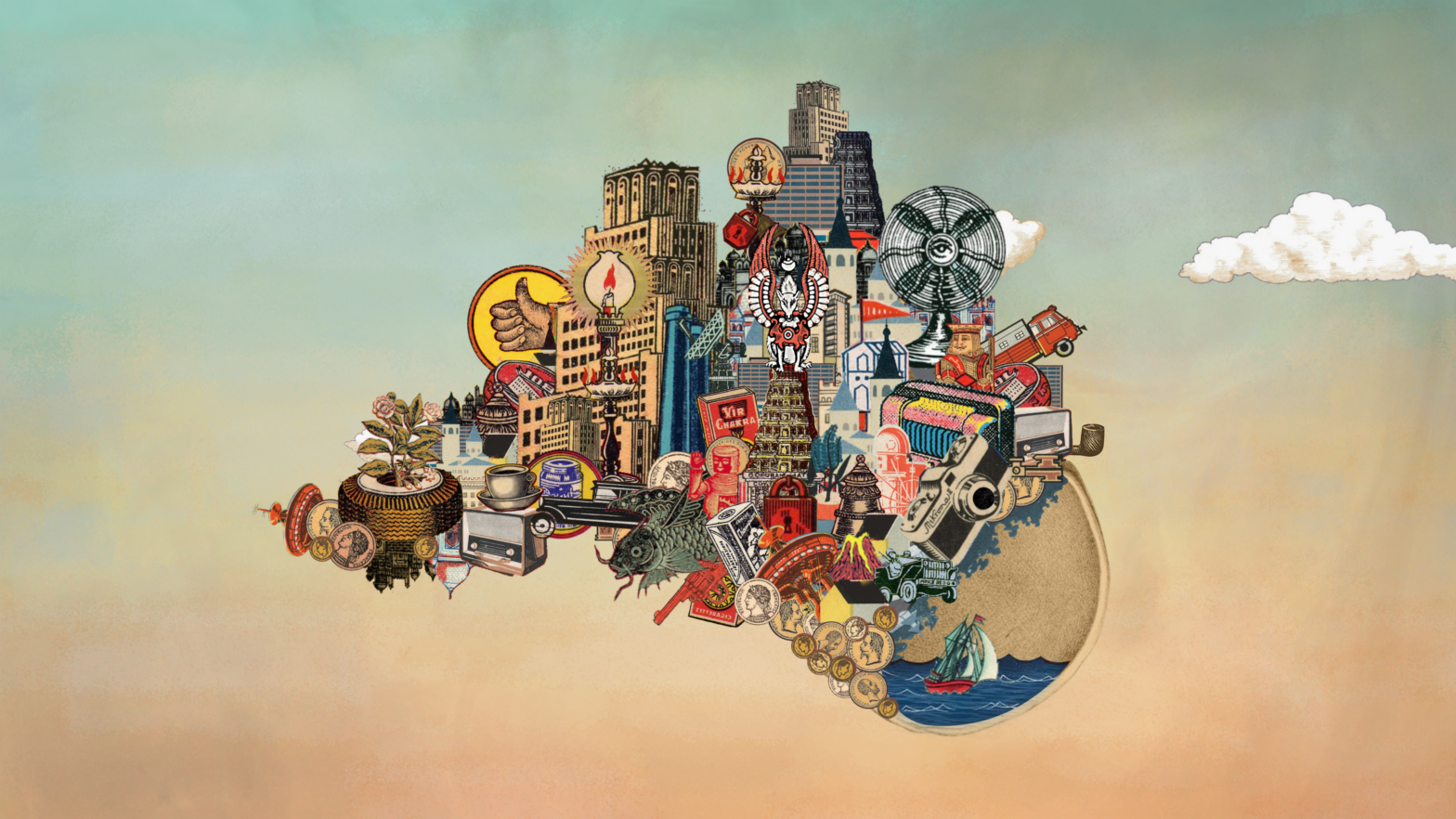

I’m the one doing generative art, the kind of art where we use the algorithms to ask the computer to draw what we want to create. The images are generated the moment you are seeing them, so it’s not a video, it’s not an animation, it’s not something that goes in a loop. The computer is running the algorithm and drawing something for you in that precise moment. As we are introducing some randomness in that algorithm, you are seeing something with the aesthetic that we want to create, but it is something unique: I cannot reproduce that moment of my art piece, it’s gone and it will never come again. It is like a video that is running but it will never be repeated.

There are two types of generative art: as artists we can choose what to sell. Arrels is a moving image that is constantly changing, and will never repeat, I think in some 6 billion years, so we can say never. This was a series of 75 pieces which are the same, so you can run the piece at your home, but another collector will have the same piece, with the same aesthetics, but looking slightly different because it is running in another unique way. In Trossets, I chose for the collectors to have a snapshot, so the series is 1,000 different Trossets which are all unique, but they are static, they do not move, change or evolve. You have a snapshot, which you can print if you like.

Trossets is long form generative art: an algorithm that generates the artwork is uploaded to the blockchain and returns a different visual composition every time it is run. As an artist, I created the algorithm but I don’t know which compositions it will create. When you buy the artwork, you run the program and get something that is generated in that particular moment and that is unique. So we just upload the code, and instead of running infinitely, you get a snapshot of a moment of that generative art piece, but that snapshot will be unique. In this case I was inspired by the Mediterranean landscape, by the white façades of houses covered in crimson buganvillea, the seaside, the olive trees, and even paella. I wanted to bring aspects of my environment and culture to a series of abstract generative drawings. Inspiration is everywhere!

“Artists were not used to talking to collectors, and it is something that I am enjoying a lot, because it is part of building this community that has emerged around digital art and NFTs.”

Anna Carreras

You know the aesthetics that are behind the collection, so you have a flavor of what it will be about, but you collect the artwork blindly, because it is in the moment that you collect that the algorithm creates that unique piece for you. My mother was a little bit skeptic, she said: “how can people buy something without knowing what they are buying?” Maybe that’s the part that you have to deal with, with some collectors, but if you trust the artist and you like her work and the concept behind the collection, then it can be even more special, because actually by buying an artwork you are contributing to create the series: the artworks do not exist until someone buys them. Trossets consists of a total of 1,000 artworks that were generated as collectors bought them, in a span of forty-five minutes.

I have a connection with some collectors, because we are asked to share our work for some exhibitions, and I ask the collectors their permission to do so. I consider that the artworks are no longer mine, they belong to the collectors who bought them. We have a nice relationship, they have a lot of feedback, they have ideas, it’s worth sharing that with them. I think that artists were not used to talking to collectors, and it is something that I am enjoying a lot, because it is part of building this community that has emerged around digital art and NFTs.

Articles like this one from El País (photo above) focus on the narrative of big sales in the NFT boom. can you comment on this narrative?

For me, this experience was awful. Many journalists, not all of them, are looking to make headlines that attract attention, and in particular in Spain we like soap operas, we like drama, and also to be envious of others. This was part of how things evolved last year, there were constantly news about spectacular sales, and I was getting calls asking me about finance and investments, which I know nothing about, because I’m an artist! After this article came out, I felt overwhelmed by the attention and I disappeared for a while.

Mario Klingemann: “the economy created on the Tezos community can support a lot more artists than just twenty superstars”

Mario Klingemann is an artist and researcher who taught himself coding in the 1980s and soon started creating his first artworks. He is known for his work with Artificial Intelligence programs, and particularly for Memories of Passersby I (2018) an AI artwork that was famously sold in March 2019 at an auction in Sotheby’s, the second to be ever sold at auction.

In 2021 he became involved in the development of the NFT community around the platform Hic et Nunc on the Tezos blockchain and has been an leading figure in this field. He has been awarded an Honorary Mention at the Prix Ars Electronica 2020 and the British Library LabsLumen Prize Gold 2018, among others.

You describe yourself as an artist and skeptic. What was you first reaction to the NFT boom? How did you become involved in Hic et Nunc?

The first time I encountered NFTs I was very skeptical. It was when I got ripped off! Somebody had taken one of my works and made a very bad remix and minted that on SuperRare, and that was how I saw there was something developing. But that was in 2019, and I had a closer look and found it difficult. At that time I had made my mark by selling the second artwork made with AI to go to auction at Sotheby’s, I got exhibitions and I made myself a name in the contemporary art world. And then came this field were initially there were only outsider artists, rebels who did not care about the art world, and actually most of the work looked that way, like something you must get used to. I saw blinking pictures and horrible kitsch and thought: “nah, this is not for me.”

So I let it rest for a while, and in early 2020, coincidentally when the pandemic started, I went to look at it again. But this time instead of trying to avoid people ripping off my work, I decided to try it myself. So I started minting under the radar, on Rarible, because it felt risky, you didn’t want your name associated with blinking gifs. But I was curious, I started minting stuff and fortunately at that time there were people in that field collecting, who knew what I was doing, so my initial mints sold very quickly. This got me more curious, because that direct experience of putting something up there and having it bought a minute later, and seeing the transaction in your wallet, that feels very good as an artist. It is undeniable that it is nice to be appreciated and actually get paid for your work.

“I started minting under the radar, on Rarible, because it felt risky, you didn’t want your name associated with blinking gifs.”

Mario Klingemann

Another issue that I always had as a digital artist, prior to NFTs, was that for me the native format of digital art is in your computer, and you had to find ways to package your art or transform it into another medium, like prints or build a whole system around it that makes it almost like an installation. The idea of just selling a digital file always felt a bit strange. I have done it: I’ve sold videos on a USB stick or so, but it felt that it was not the native way of selling digital art. Now NFTs suddenly allow that, and they allow to sell works in small resolutions, experimental stuff which was pretty much meant for the screen. After my initial skepticism, I got really curious and started doing what one is supposed to do, to become your marketer, to build your brand in this space. This is a bit alien to me, and in a way I feel that I am still doing it wrong. If you want to really be successful in the NFT space you have to swamp your followers with announcements and specials, love your collectors… I’m not doing that. This whole thing never felt natural to me.

Marketplaces like Rarible or SuperRare were not build by people who had an art background, but by coders and entrepreneurs, and in one way that was good because it was innovative and moved quick, but the whole focus was so much on selling and ranking that the art was not important. It was all about volume of sales. This didn’t feel right to me. There were also many discussions, by the end of 2020, about the ecological impact of minting NFTs in the Ethereum blockchain.

So I started looking for alternatives: there was the alternative of Proof of Stake blockchains, but there was simply no market there. Then in early 2021, Tezos added NFTs to their smart contracts, and by accident I stumbled upon a tweet where someone told about Hic et Nunc, an experimental site where you could mint your NFTs on Tezos. At that time, it was not even a marketplace, just a site that you could try out. You could upload an image and mint it for almost no money, a few cents. The whole Tezos thing was like a blank canvas at the time, it had been around for nearly as long as Ethereum, but it wasn’t as popular. It felt like a new continent, where you could start something new, with different rules.

“I think that because we started from a blank canvas, the whole community could develop in a different way than in Ethereum.”

Mario Klingemann

I tweeted about the work I had minted on Hic et Nunc, and since I had some followers, people asked to buy it, and I told them: “well, if you send me some Tezos I will mint the NFT and send it to your wallet.” So in one hour the whole edition was sold, and the fact that it was environmentally sustainable, and that Hic et Nunc was not hyped like other marketplaces, was attractive to a lot of people in my inner circle, particularly artists who had not wanted to touch NFTs, so in a few days a lot of artists with a good reputation started minting there as well. Another advantage of the Tezos cryptocurrency is that is accessible to everyone price wise. Even someone who only made, say $50 a week, could mint on Tezos. So the community developed very quickly and the beauty was that it was also experimental, and it grew organically, collecting from each other, with a very different spirit from what you could see on Ethereum. Around September 2021, the founder of Hic et Nunc, Rafael Lima, pulled the plug and erased the site, but the magical thing about NFTs is that they do not exist on that site, they exist on the blockchain, so within one or two days people built mirrors of the site, and the community moved on.

I think that because we started from a blank canvas, the whole community could develop in a different way than in Ethereum. But it is not about one being good and the other one bad. Right now, artists start in Tezos, and then if they want to make it big, they go to Ethereum. And since yesterday, Ethereum is even environmentally sustainable, too. So, we’ll see how things develop.

You have had a continuous collaboration with Tezos over the last year. Do you feel that the community around Tezos is becoming less “renegade” and more “conventional”, or is there still space for experimentation and a bit of a rogue spirit?

There is space for both. Right now, there is a platform in which you can mint text, so there is still breathing ground for new ideas. And at the same time, the Tezos Foundation, which has a DAO structure, seems to be doing things for the right reasons. So far, I’ve had good experiences with them, and they do not seem to try to push things in a certain direction, they just provide possibilities to people. Anyone can apply to the Tezos Foundation with a project and get a grant if it is approved by a majority. They are also present at Art Basel, spreading this idea that on Tezos you can find real art. How they present the art, it seems closer to how it is displayed in the contemporary art world.

Also, it is not true that everything is cheap, so I think it can be a space for artists to build a reputation and also make money. FxHash has become the de facto platform for generative art and whilst the single pieces might be affordable, if you sum it up, there is a decent amount to be made. Also, I feel like focusing on mega sales is not the way to go, because if one artist takes, let’s say a million dollars, that money is gone out of the cycle, while on Tezos you have this circular economy where artists earn money from their NFTs but are also very active in collecting from other artists. This can support a lot more people than just twenty superstars.