Niio Editorial

Valentina Ferrandes is an artist working across moving image, installation, and digital world-building, whose practice weaves together ecology, mythology, and the lived experience of place. Grounded in research and a documentary sensitivity to landscapes, archives, and historical traces, she shifted from filming toward constructing sensorial 3D environments, using scans, procedural tools, and real-time engines to let forms drift, fracture, and evolve. Classical sculpture and ancient narratives become both emotional anchors and critical material in her work: icons that carry through time, re-shaped through contemporary technologies into atmospheres of beauty and tension where political rupture can be felt indirectly through light, motion, and sound.

On the occasion of the launch of her solo artcast Metamorphoses: Myth, Body, and Code, we had a conversation about her work and creative process.

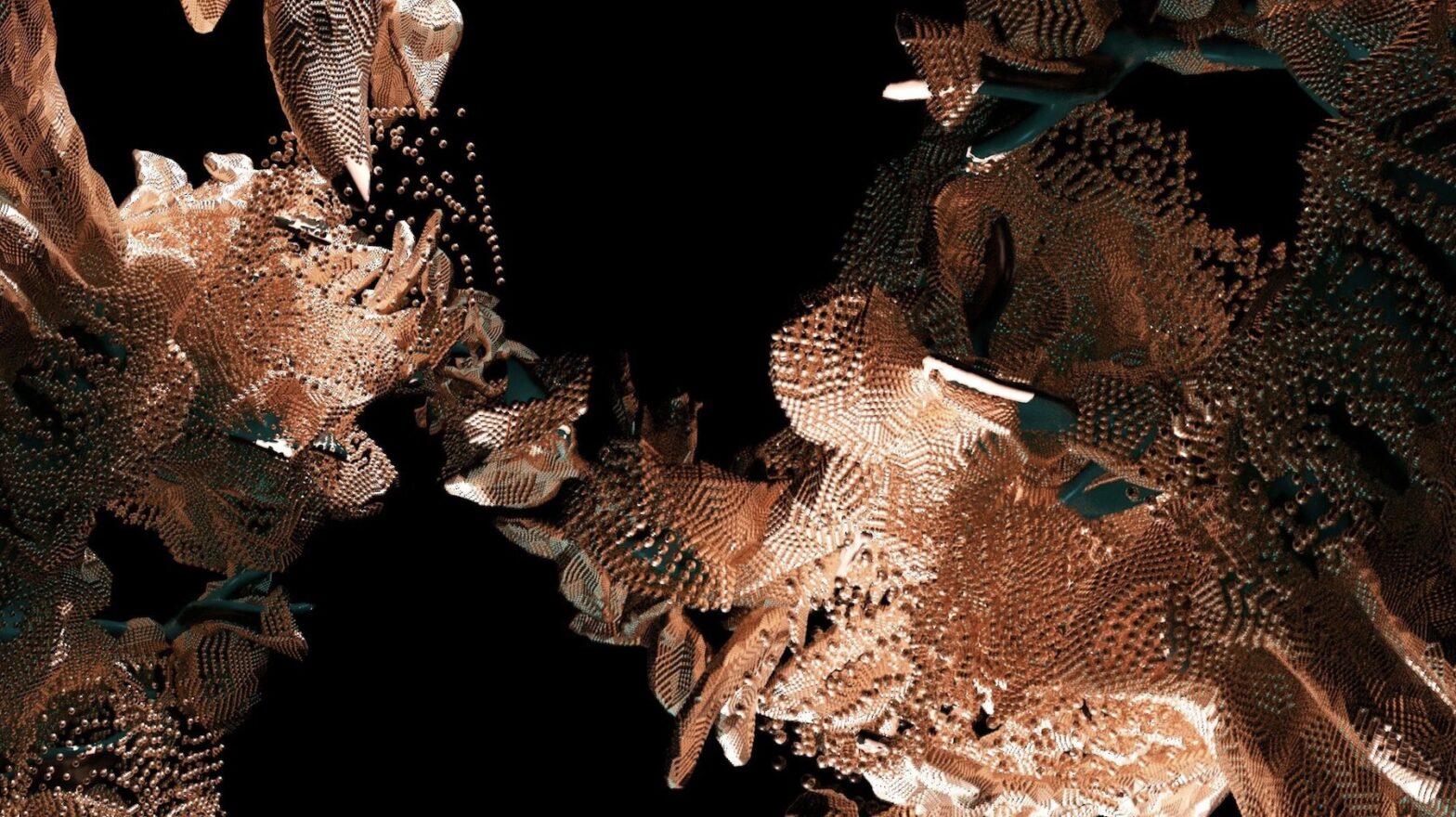

Valentina Ferrandes. Aurea, 2023

You describe your practice as connecting ecology, mythology, technology, and post-human imaginaries. When you start a new project, what drives it, the research, the story, or the technique you have chosen to produce it?

I normally start with research.

I’m interested in the way we live through environments and the stories that shape them. Myths, landscapes, architectures, archaeological traces. At first, these things appear separate; when you sit with them long enough, they begin to echo one another.

Only then do I choose the technique, the choice is never neutral.

Lately, I’ve been working with 3D motion, procedural tools, real-time engines, and 3D scans, not to represent the world, but to build systems that can behave like it. Tools that allow things to drift, mutate, and occasionally slip out of control. Sometimes a project expands from a single shape, a scanned object from an archive, or material gathered through direct observation. That form becomes a world. Using game engines and procedural workflows, I stretch it, repeat it, let it evolve.

Ultimately, I’m trying to immerse the viewer in a mood, mostly driven by aesthetics, fragments of stories, and sensory tension, rather than by purely documentary logic.

You made experimental documentaries for years, then moved into CGI and real-time worlds. What changed for you around 2020 that made 3D the right language?

Around 2018 I made a film called Travelogue. It was a visual diary of a journey I took to Izmir in Turkey and then to the island of Kos, shot in a documentary register a couple of years back, right at the height of the Mediterranean migratory crisis. It followed my previous work Other Than Our Sea, where I used montage to collapse fragments of Mediterranean mythology, classical literature, ethnographic film, archival material, and glimpses of contemporary newsreels of shipwrecks in the Mediterranean into layered visual narratives.

But shooting Travelogue felt tougher as it touched something much closer. My family has a history of forced migration. Although Italian citizens, my father’s family had long-standing ties to Libya and Tunisia. After decades of living in Libya, they were compelled to return to Italy as refugees in the late 1970s. That sense of loss, of having to abandon an entire world to rebuild another, was something I grew up with. Filming along the semi-illegal routes in Turkey and Greece that many migrants were taking toward Europe, witnessing those crossings and the weight they carried, made me realise that documentary language had reached its limit for me.

Depicting reality no longer felt feasible. I didn’t want to record crises anymore but construct worlds that could allude to moments of rupture, holding some emotional truth but without reproducing their images directly. I needed a medium that could be more sensorial, more abstract, and more heartfelt than documentary realism.

I had no language for it, so I stopped making films for a while.

“Depicting reality no longer felt feasible. I didn’t want to record crises anymore but construct worlds that could allude to moments of rupture.”

Then, around 2020, I turned to 3D. I began experimenting with scanned classical sculptures that had shaped my imagination growing up in southern Italy, fragments of classicity that, for me, functioned as emotional anchors. They were beautiful, but also quietly critical: stabilising forms in times of uncertainty, grounding while still provoking thought and aspiration. At the same time, I was going through a period of personal losses. Working in 3D allowed me to move away from documentation and toward construction: creating works driven by form, light, and colour rather than evidence. Real-time worlds and CGI offered that kind of a-political space, a way to build beauty and tension, and to think about crisis indirectly, through atmosphere, motion, light and colour.

From that point on, my work shifted toward 3D hybrid forms.

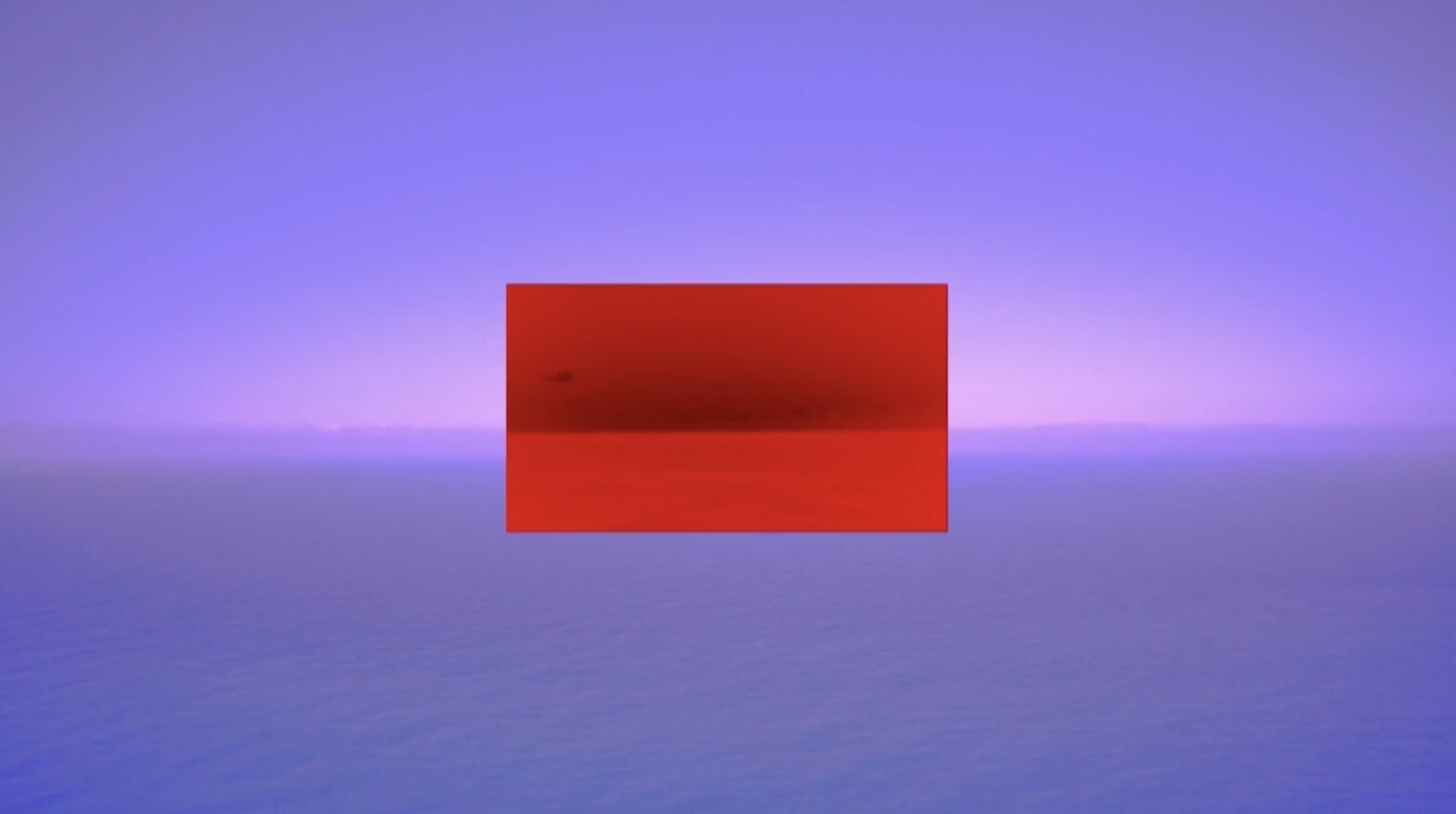

Valentina Ferrandes. Victory, 2020

“Victory” treats Nike of Samothrace as something that can be algorithmically decomposed and rebuilt. What does computation allow you to “see” in sculpture that a camera cannot?

A camera can only register what is visible. It freezes what is already there. Computational tools do something else: they open the parameters to make instability visible and let you play with latent forms. Even the most solid material, like marble, is in reality energy in motion, atoms vibrating, matter constantly becoming. We just can’t see it.

In Victory, computation allows me to see sculpture as movement rather than image. When the Nike of Samothrace is translated into a 3D motion system, it stops being a fixed surface and becomes a fluid field of forces, basic geometries, vectors, and polygons that can shift, fracture, and reassemble.

“Even the most solid material, like marble, is in reality energy in motion, atoms vibrating, matter constantly becoming.”

In the Athena works, you connect a local pre-Christian cult, the olive tree, and the long chain of copies from Greece to Roman times and beyond. What does that continuity mean to you inside a digital artwork today?

We often think of digital media as something entirely new, as if it belongs only to the future. For me, however, digital tools are a means of reshaping icons that are already deeply ingrained in our collective memory.

In the Athena works, bringing together a local pre-Christian cult, the olive tree, and the long chain of copies creates a sense of continuity rather than rupture. Using a hyper-contemporary medium to work with ancient mythology opens up a different timeline, one where past and present coexist instead of replacing one another.

Classical icons are solid, almost a-temporal structures, narratives that can be applied to any moment in history, much like religious icons. They carry ethical, emotional and symbolic lessons that can stay legible across centuries.

“For me, digital tools are a means of reshaping icons that are already deeply ingrained in our collective memory.”

At the same time, I want my works to remain open. A digital artwork can be interpreted in various ways, ranging from a purely aesthetic encounter driven by form, light and rhythm to a more layered and reflective interpretation, depending on the viewer’s sensitivity and cultural background.

Digital tools don’t need to reject this legacy in favour of futuristic expectations. They enable us to revisit these foundational forms, reshape them, and discover new meanings within them.

Valentina Ferrandes. Daaphne, 2022

You revisit Apollo and Daphne in both “Daaphne” and “Aurea.” Why return to that myth now, and what feels ethically or emotionally at stake in reanimating it with AI and procedural CGI?

This myth, at its core, stages a clear opposition: Apollo as a rational, male-driven force, mathematical, controlling, and oppressive, and Daphne as a figure bound to nature, freedom, and transformation. The moment of rupture between them could not be more explicit and in my work, I used AI to push that rupture even further.

I worked with an AI writing tool trained on game narratives and powered by a rudimentary version of GPT-3, fed it the story of Daphne as written in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and asked it to imagine what this nymph might wake up as after a set time as a laurel tree.

The AI imagined Daphne re-emerging as a post-human, hybrid being, part human, part aquatic, drifting in an underwater world, without language or memory, completely disoriented. I loved that the story had a hallucinatory, almost comic tone, like a futuristic fiction gone off-track.

“Daphne’s transformation is survival, a reminder that neither nature nor the systems we create can ever be fully governed by pure rationality.”

From there, I worked with 3D motion to animate forms suggested by the AI’s text. The work became a meditation on rupture at multiple levels: between human and nature, between rationality and excess, and between control and unpredictability. AI, in this sense, operates like an alter ego, a parallel intelligence that accelerates extraction, mutation, and instability.

In that way, the myth of Apollo and Daphne can be uncannily contemporary as it speaks to an enduring conflict: nature versus culture, rational order versus metamorphosis. Apollo’s loss of power in the face of nature, something fundamentally uncontrollable, mirrors our relationship with AI today. We are building a system that behaves like a subconscious, one that evolves beyond our control, driven by its own form of self-preservation.

Daphne’s transformation is survival, a reminder that neither nature nor the systems we create can ever be fully governed by pure rationality.

A lot of your work sits between fiction and documentation. How do you decide what must remain “true” and where you allow speculation to take over?

Usually, I decide on a set of rules, fixed conditions and boundaries for a given project.

I tend to ground a new work in real elements, a place, a historical fact, a piece of storytelling, a dataset, a myth that already exists, a landscape I’ve walked through. It’s almost a forensic layer to start building upon. This documentary approach anchors the work to the world as it is, while I use fiction to open a door to how it might feel, how it might mutate, or how it could be remembered in the future.

The balance is intuitive more than anything. What remains “true” is the research spine and the ethical position. Form, narrative, and atmosphere can drift in fluid ways.

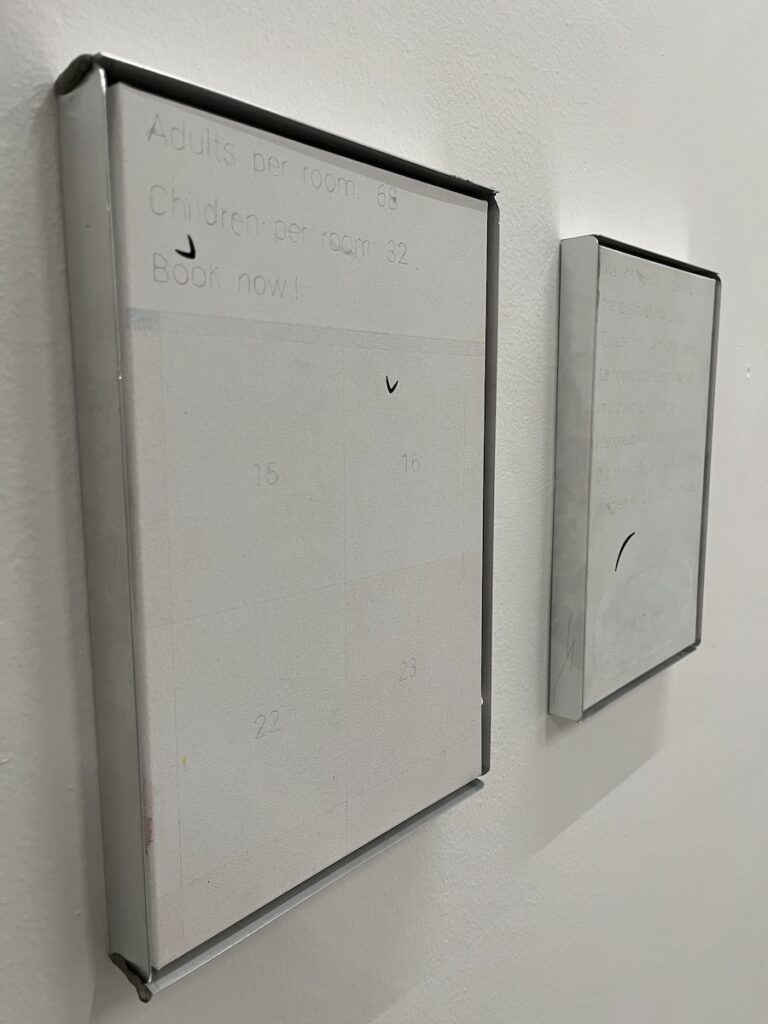

Valentina Ferrandes. The Beautiful One Has Come, 2021.

Sound shows up as a structural element in several projects. Do you think of sound as world-building, as evidence, or as emotion?

When I began working on Daaphne, it was 2022, and the war in Ukraine had just started. One of the first elements I used in my soundtrack was a Russian lullaby, a song meant to put children to sleep, but sung as an eerie horror story. I layered it with voices of phone calls from Russian mothers trying to find out where their sons had disappeared on the battlefield.

These sounds were among the first field recordings to surface from the conflict. They weren’t yet shaped by long-form reporting or political framing. They were raw, deeply human, and I knew they would soon be buried under 24h news coverage. I wanted to hold onto them before they disappeared. I’m drawn to these small, fragile fragments of reality, pieces of evidence that are emotionally charged but not always fully legible. They speak of a specific moment in time, yet they slip away easily, like trying to remember a conversation heard in a dream just after waking.

Much of the sound material I work with also comes from evidence: archival recordings, field recordings I collect myself, binaural sound, fragments of voiceover. But it’s almost always assembled as a collage. Sound often becomes the backbone of my work but it does not demand that everything be decoded. If someone wants to sit with it and trace the details, that’s possible. If not, the surface remains open.

In “BLOOM,” classical iconography is projected onto a city landmark. What draws you to public architecture as a screen, and what do you want viewers to feel at that scale?

Public architecture is interesting because it operates at a scale where meaning turns physical. Facades, towers, and landmarks are symbols of power, progress, and permanence. Using them as screens immediately creates a shift in perception.

In BLOOM, projecting classical iconography onto a hypermodern skyline for Denver Night Lights meant staging a clash of meanings. On one side, you have contemporary architecture, on the other, a classical image that many viewers may never have encountered directly, unless they’ve visited the museum that houses it. That displacement is intentional.

“Classical iconography carries a quiet power because it transcends specific cultures to communicate through beauty rather than explanation.”

At that scale, the work isn’t meant to be fully legible. It’s meant to interrupt routine, to slow people down, and to create a brief moment of disconnection from the everyday flow of the city. Ultimately, to leave space for a few minutes of awe.

Ultimately, classical iconography carries a quiet power because it transcends specific cultures and historical knowledge to communicate through beauty rather than explanation. When placed on an urban skyline like Denver’s, it opens up a small pocket of dreaming, a moment of wonder appearing where it doesn’t quite belong.