Pau Waelder with Karin Vicente and Diane Drubay

Is there a need for art during an ecological crisis? This provocative question is the starting point of the exhibition Art in the Age of the Anthropocene, currently on view at the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn (Estonia). The exhibition explores Estonian art history from an ecocritical perspective, addressing how nature, but also the industry and the impact of human activity on the environment, have been depicted in painting, sculpture, photography, and other media, including video art and performance. Such an approach is particularly interesting in itself both for bringing new perspectives to Estonian art history, and for suggesting a reflection on our relationship with the environment from the vantage point of a selection of artworks spanning more than a century. However, what makes this exhibition even more relevant to our present time is that it is the outcome of a three-year-long project debating the role of the museum in the Anthropocene and particularly during a climate emergency.

What should an art museum do at a time when sustainability is no longer a choice, but a need? What should be the institution’s role in raising awareness about the way human activity fuels the current climate crisis? How can art museums become hubs for reflection, and possibly action, to face a growing environmental disaster? These are hard questions to answer, and we cannot expect a single project or institution to be able to answer them. In fact, this has been an ongoing debate for many years among museums experts, in forums such as the Museums Facing Extinction programme carried out since 2019 by We Are Museums in collaboration with the EIT Climate-KIC agency. However, the exhibition at Kumu offers a good example of how sustainable exhibition principles can be put into practice, and furthermore communicated to the visitors.

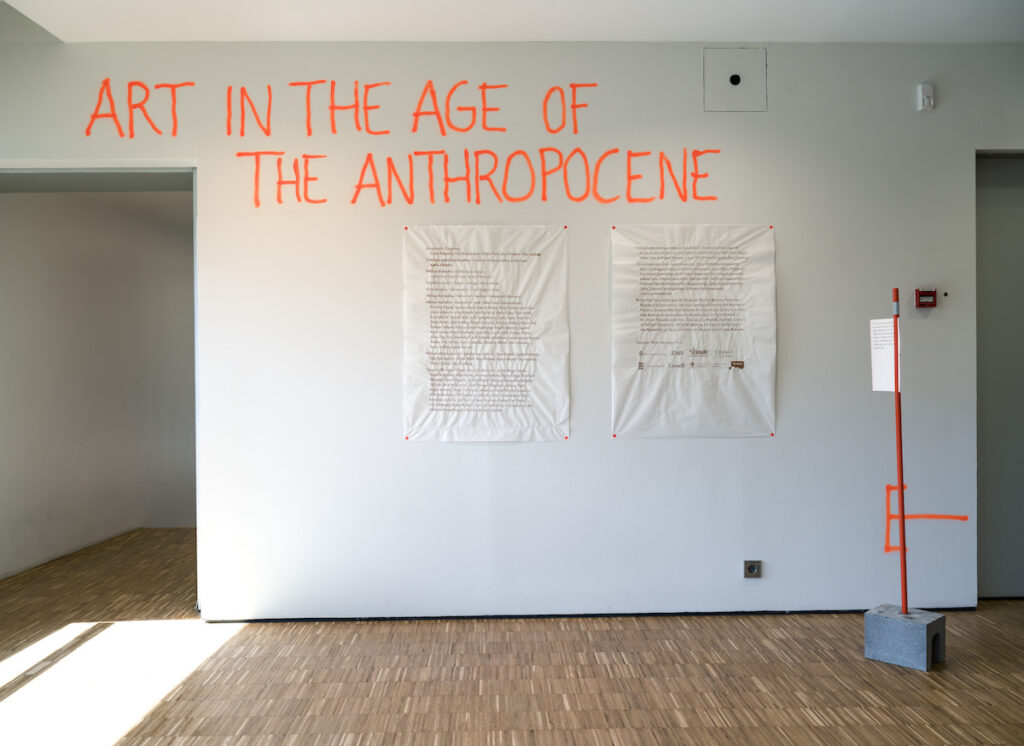

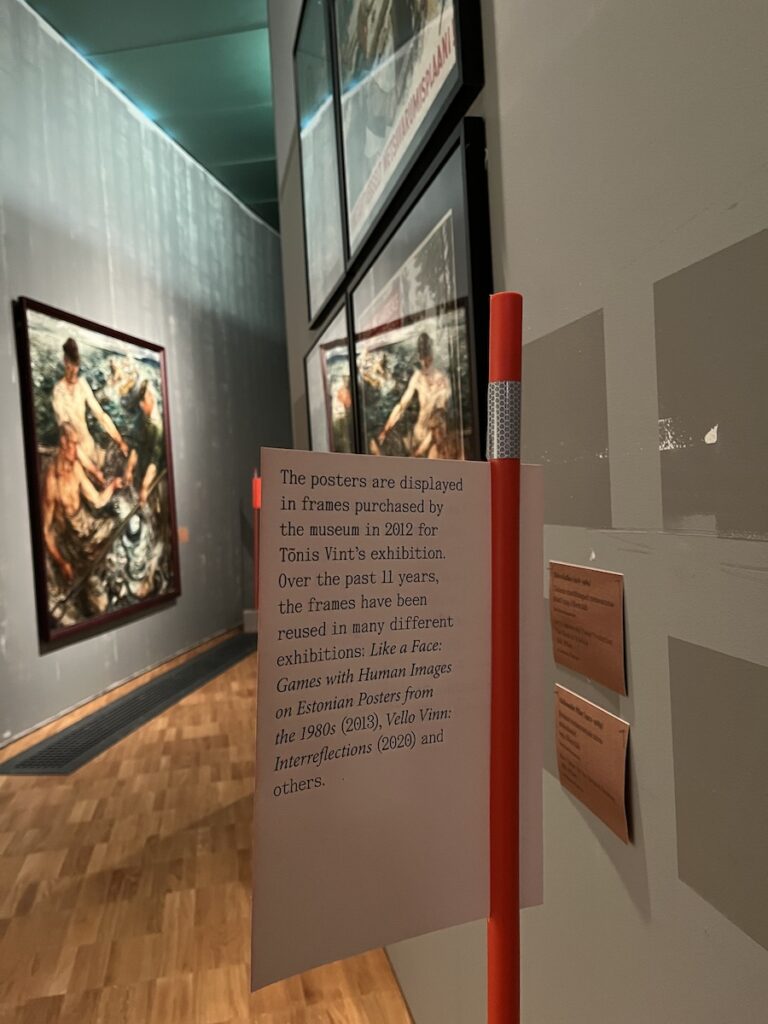

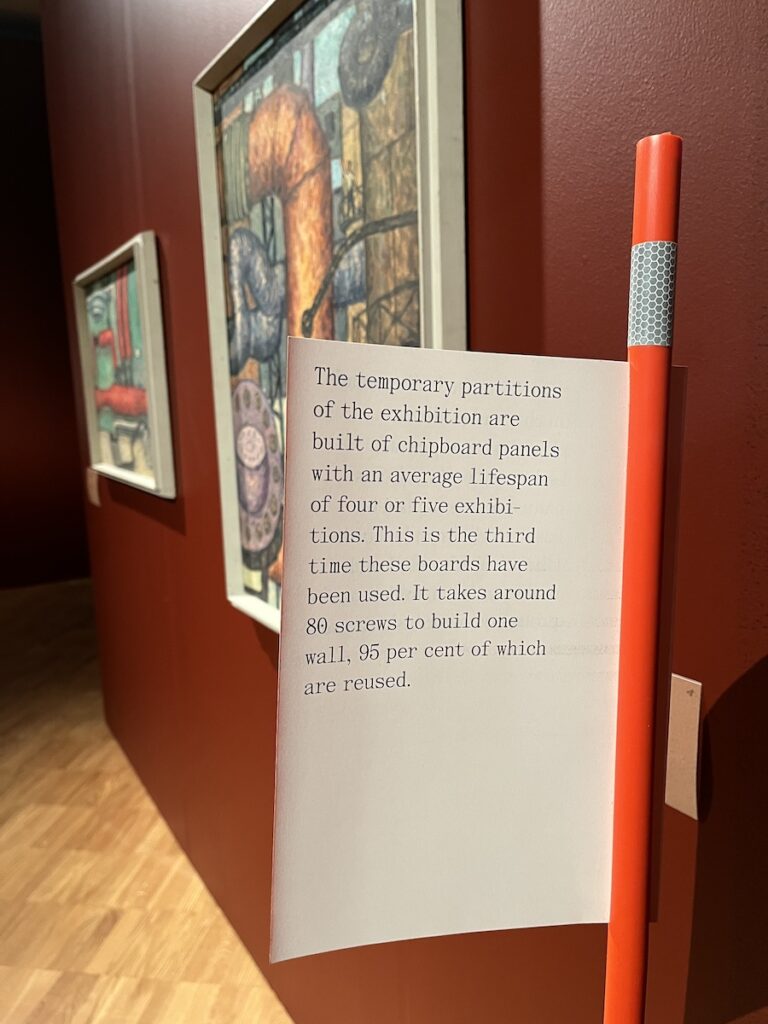

This is actually the aspect in which this exhibition stands out, questioning its own museography and drawing attention to experimental solutions for a more sustainable exhibition design with highly visible informative signs. Before entering the exhibition, visitors encounter an unusual sight: instead of using vinyl lettering, the exhibition title has been spray painted on the wall, while the curatorial text is displayed on two large sheets of paper. Next to them, a thin red pole stands on a concrete brick, holding a cardboard label with additional information. These freestanding labels are scattered across the rooms, providing an additional reading of the exhibition in terms of the sustainable practices applied to this particular curatorial and museological project.

Thanks to them, we learn for instance that clay paint has been used to create the wall texts and labels, and that the labels are UV-printed on leftover cardboard, thus avoiding the use of plastics. Different wall paint solutions have been tested, considering their ecological footprint, price, amount of work required, and efficacy. We also learn that the posters in the exhibition are displayed in frames that have been used multiple times during the last eleven years, or that a painting that has been in storage in the museum’s collection for 78 years is now on display for the first time. Sustainability therefore goes beyond the choice of materials used and involves larger decisions about the management of the museum’s collection or the carbon footprint of an exhibition that includes artworks brought from remote locations. Art in the Age of the Anthropocene does not pretend to solve all of these questions but rather to raise awareness about the challenges that museums face on their path to sustainability. The freestanding red poles and experimental solutions give the appearance of a construction site and seem to convey the idea that it is all in the works. This is actually an honest way to address the issue, and also to involve the visitor, who is encouraged to consider how to contribute to a sustainable museum experience.

An expert’s view on sustainability in museums

To better understand the ideas and the work behind Art in the Age of the Anthropocene, I had a brief exchange with Karin Vicente, the head of the sustainable work group at the Art Museum of Estonia.

Karin Vicente is an art historian based in Tallinn, Estonia. She works as a programme manager and curator at the Adamson-Eric Museum. She is the head of the sustainable work group at the Art Museum of Estonia. Currently she is working on the project A Model for a Sustainable Exhibition.

The exhibition Art in the Age of the Anthropocene has had a long gestation period of over three years. Can you highlight the main tasks and processes that have taken place during this time?

The preparation of the exhibition is a part of a research project. It helped us analyze our collections (as well as collections of other museums) from an ecocritical perspective. Beyond the content, the exhibition has also initiated discussions about the green transition in the museum. How can an art museum minimize its ecological footprint? We organized a few seminars and discussions in the museum, involving participating artists and designers.

“We wanted to raise questions among the audience, such as the price of being part of a global art network.”

The exhibition is characterized by a double educational approach, on the one hand selecting artworks that speak about the representation and appropriation of the environment in Estonia, and on the other hand pointing out the sustainable exhibition practices carried out in its mounting. How have you combined these approaches?

The “red flags” indeed reflect the issues we discussed with curators and the exhibition team during the process. However, the selection of artworks was made by curators, following the narrative of the exhibition. We didn’t plan to create a zero-waste exhibition. For example, we invited international artists to contribute to the exhibition and designed a special exhibition layout considering eco-design aspects. We wanted to raise questions among the audience, such as the price of being part of a global art network. The pollution generated by air travel casts a shadow over bringing international art to Tallinn, yet it makes more sense than visitors traveling to the country of origin of each piece to see it. We want to be part of a global arts network, but how do we balance the pros and cons?

The sustainable exhibition practices have involved collaborations with third parties, such as the Tallinn Book Printers, to obtain leftover material. Can this lead to continuous collaborations? Is it possible for a museum to fully transition into using donated materials for purposes such as wall labels or brochures?

We collaborate with many companies, and there is a growing demand and consciousness concerning “green solutions” in the field. In some cases, it might be reasonable to create an exhibition using only reused/recycled/donated materials, but we also need to consider other aspects, like the security and well-being (climate conditions) of our collections. Handmade silkscreen texts and labels on waste paper were playful experiments, but they demanded a lot of human resources. Therefore, I’m afraid we won’t be able to do it every time.

Reusing elements purchased by the museum from previous exhibitions is a good practice both environmentally and economically, and currently most museums have a certain amount of reusable stock. How can this practice be even more effective and sustainable, balancing the specific needs of artists and curators with those of the museum?

The only restriction to reusing more materials is the limited storage space we have. We have discussed with other museums and institutions the idea of a platform that would facilitate the exchange of different showcases and materials between different institutions, but it still needs to be developed.

Wall painting is a major element of exhibition design, as it conditions the visual perception of the artworks. How do you see the solutions you have tested in Art in the Age of the Anthropocene being applied to other exhibitions?

The experimental design decision our team made involved testing different wall paint solutions. We were looking for the most economical and sensible solution, so we have analyzed the properties of clay, casein, linseed oil emulsion, and acrylic paints: their ecological footprints, prices, covering capacities, drying times, scratch resistance and ease of removal, and the required amount of work. The result was visually effective as we also tested different painting styles (using less paint). I think it’s a matter of taste; different wall paint solutions can be used when exhibiting artworks from different periods. There are obviously other methods to use wall paint in a more sustainable way. I think the trick is to find a good balance between the desired outcome (how it looks) and how we achieve it.

“Handmade silkscreen texts and labels on waste paper were playful experiments, but they demanded a lot of human resources. Therefore, I’m afraid we won’t be able to do it every time.”

Video and digital art are increasingly present in contemporary art exhibitions, which demands that museums have screens, projectors, computers, and other equipment that is also commonly used in educational activities. How does incorporating digital art into the museum align with sustainability goals? How would you compare it with traditional formats (painting, sculpture) in terms of shipping, maintenance, and storage, and the need to participate in the global art scene?

Indeed, both digital and traditional art forms have their ecological footprints. Traditional artworks need to be kept in a controlled climate that consumes a lot of energy. Digital artworks require computers, etc., and they have a digital footprint. However, we need both, and I think it doesn’t make sense to compare them.

Climate control is necessary inside the museum, not only to make visitors comfortable, but also to preserve the artworks. How can it be made more sustainable? What are the challenges for a museum in Estonia, where the difference between summer and winter temperatures can be extremely high?

We are updating our HVAC systems at Kumu in 2023; this requires a significant investment. This year, we also initiated a discussion in the museum to form our opinion about the Bizot protocol and weakening the climate standards. These are not easy decisions to make, but we are working on them.

Is there a need for art during an ecological crisis?

Considering the issues raised by the Kumu exhibition in a wider scope, I asked Diane Drubay, artist and founder of We Are Museums, about her views on the sustainability of art museums and a possible answer to the role of art in our current climate emergency.

Diane Drubay is an artist whose work focuses on better futures and nature-awareness and a researcher working towards the transformation of museums and art through various communities, events and programs, internationally since 2007. Founder of We Are Museums and WAC-Lab. Member of Museums For Future.

What is your opinion about the interplay of artworks and information in Art in the Age of the Anthropocene?

In my opinion, the greatest challenge to overcome when we want to adopt sustainable exhibition practices is taking the first step. There are endless lists of practical sustainable actions, but they are often repetitive and tailored to a global audience rather than a local or personal one. Over the years, I’ve learned that it’s by sharing our personal stories that our actions can resonate with others. So I don’t hesitate to talk about what I do or don’t do any more, and to explain how I do it and what impact it has on my daily life.

In the “Art in the Age of the Anthropocene” exhibition, we find this very personal way of talking about what has been done and why, but also a very practical one. All the details provided give visitors the chance to draw inspiration from them and apply this mindset to their everyday lives, or even their professions. I would love to see all these practical insights shared online in a global “ressourcerie” for museums on their climate journey!

Also, while museums tend to have the reputation of being large, secretive or inaccessible institutions, showing such openness and sincerity highlights the human beings who work in this museum and who, like everyone else, have moments of questioning and try to do their best to reduce their carbon footprint. Such honest behavior addresses the human being before the visitor. Leaving questions open invites dialogue and shows great humility, while sharing insights can be inspiring.

In a recent article on Art Review, Marv Recinto states that art exhibitions about ecology “often feel futile in the face of real environmental devastation” and calls for “a more concerted effort towards action.” As an artist addressing this subject, how would you respond to this? Is the effort carried out at KUMU a step in this direction?

As there are many different types of disaster, there are many different ways of approaching an environmental emergency. Some people need to feel emotionally involved in order to act, others need figures and scientific facts to speak to their rationality, and still others need to be on the ground, collaborating with others, and so on. What I see is that many artists have several points of action, and the creation of stories or emotions complements local community action or changes in behavior. If we want to make a lasting impact and see behavior change profoundly, the approach must be multiple and complementary. As in nature, it is the diversity of species that makes a land fertile.

“If we want to make a lasting impact and see behavior change profoundly, the approach must be multiple and complementary. As in nature, it is the diversity of species that makes a land fertile.”

Karin Vicente states that both traditional art formats (painting, sculpture) and digital art have their carbon footprint, and that we need both, so it makes no sense to compare them. What is your opinion about digital art and sustainability in museums?

Exhibiting digital art and, above all, preserving it are key priorities for museum professionals today. So now is the perfect time to experiment with sustainable practices in my opinion. Many museums and associations are already well advanced in their search for a sustainable digital strategy.

Like KUMU did beautifully, low-tech cultural mediation within the museum is a very good way of offsetting the carbon footprint of hosting servers and other carbon costs. But museums can also seek to reduce their carbon footprint by implementing actions in favor of biodiversity, reducing their water consumption, maintaining or creating forested or natural areas around the museum, thinking in terms of slowing down, circularity and renunciation, or supporting the local before thinking global.

“A digital work of art can reach more people in a global and inclusive way.”

And I agree with Karin Vicente that comparing the different media and their carbon footprints makes no sense, because we would also have to add a measure of the impact in terms of raising awareness, encouraging people to act and changing behavior, but also in terms of the number of visitors reached. A digital work of art can reach more people in a global and inclusive way.