Interview by Pau Waelder

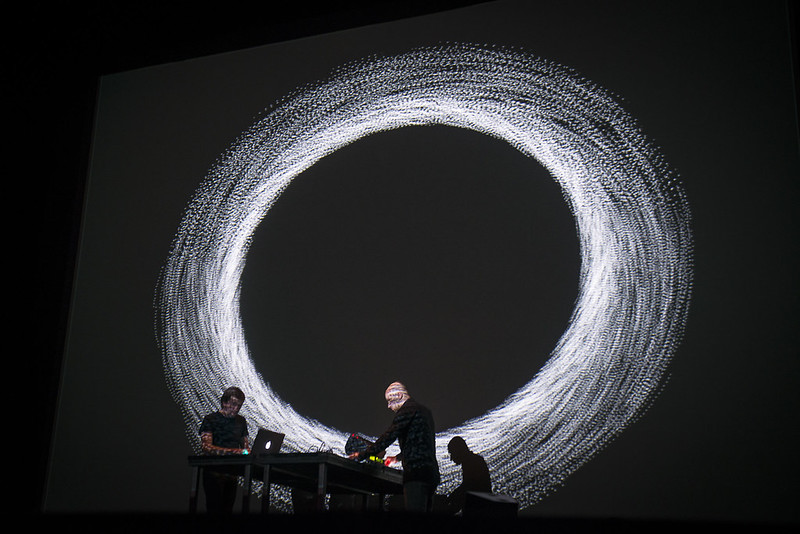

Canadian artist Stuart Ward has been inspired by ancient cultures since his childhood, and by a pragmatic approach to art making that had him incorporate digital tools into his traditional arts education. Living in Tokyo, he joined the live VJ scene in the mid 2000s and began collaborating with musicians, dancers, performers, and visual artists. Returning to Canada in 2010, he started an experiential design studio, working with internationally recognized brands such as Porsche, Cadillac, Lyft, TED, Asics, and Heineken.

His experience in both the traditional art world and the advertising and design fields shapes his perception of art as a form of creative expression that transcends boundaries and communicates with an audience on any possible context: not just in the white cube of the gallery or museum, but also on media façades, projections and screens in private and public spaces.

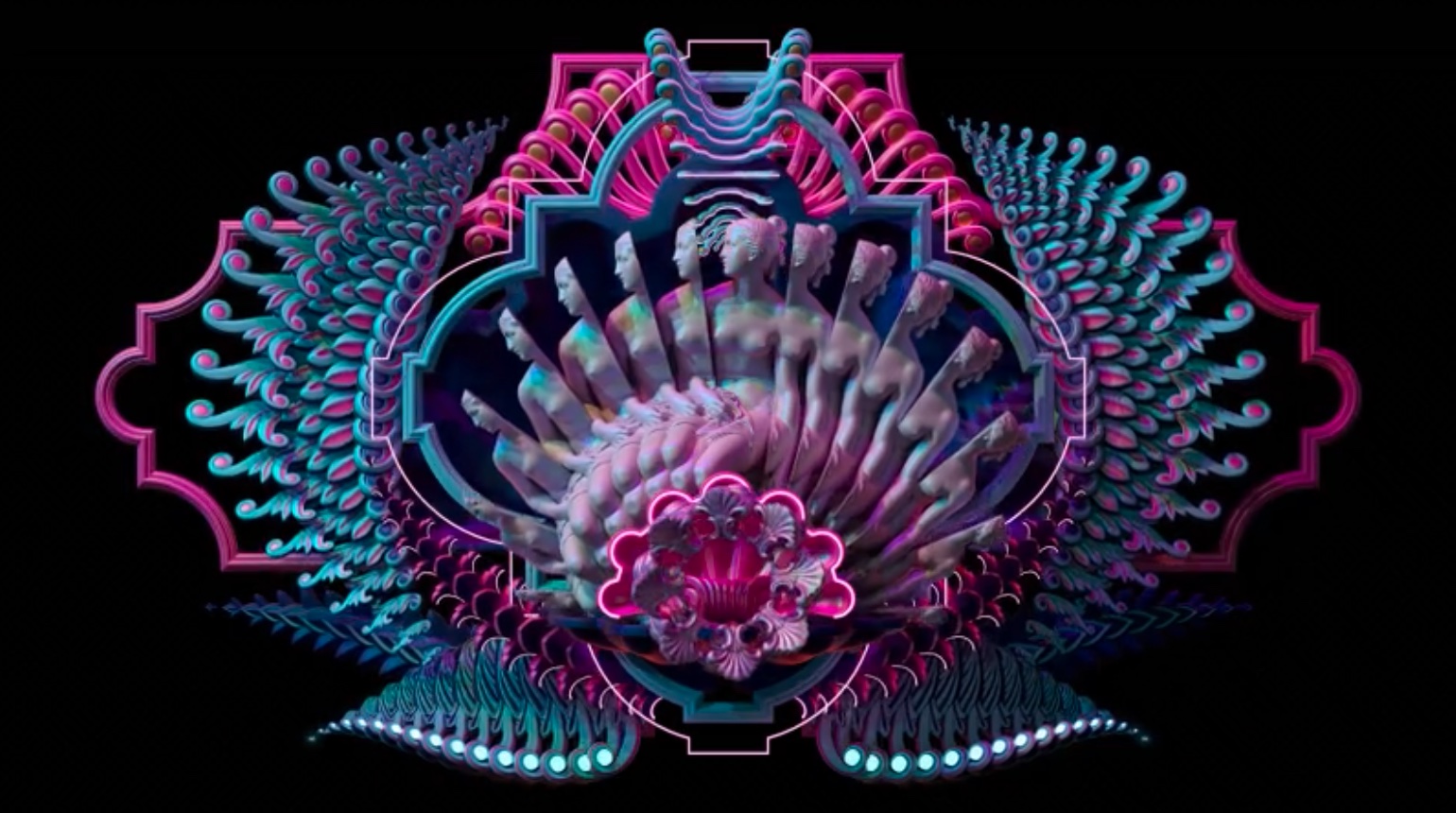

MUEO is the chosen name for his visual art persona and a creative project that references from Greek and Roman sculpture, Baroque architecture, treatises on visual perception, advertising, and the neon lights of the streets of Tokyo. On the occasion of his solo artcast Mueo – The Initiation, we talked about his work and the topics it explores.

Take MUEO’s Neo-Baroque compositions to your screen

Stuart Ward, Venus, 2023

How would you describe the way Greek and Roman iconography, as well as that of other traditions, such as Buddhism for instance, is being incorporated into our contemporary culture, e.g. as a symbol of power or authority, or to express refinement? How does this apply to your work?

Greek and Roman architecture was adopted by several powerful nations and used as a symbol to perpetuate their power through association. Some of those nations ended up leaning more towards fascism, others went entirely that way. Cultural symbols have been permanently ruined in parts of the world. Architecture of power and dominance being built today has since shifted to the opposite end of the spectrum while simultaneously holding on to Greek and Roman forms. It’s almost as though the powerful are seizing both ends of the spectrum. There is a lot of nasty brutality in history, everywhere in the world. Learning about it is a great start to avoiding repeating it.

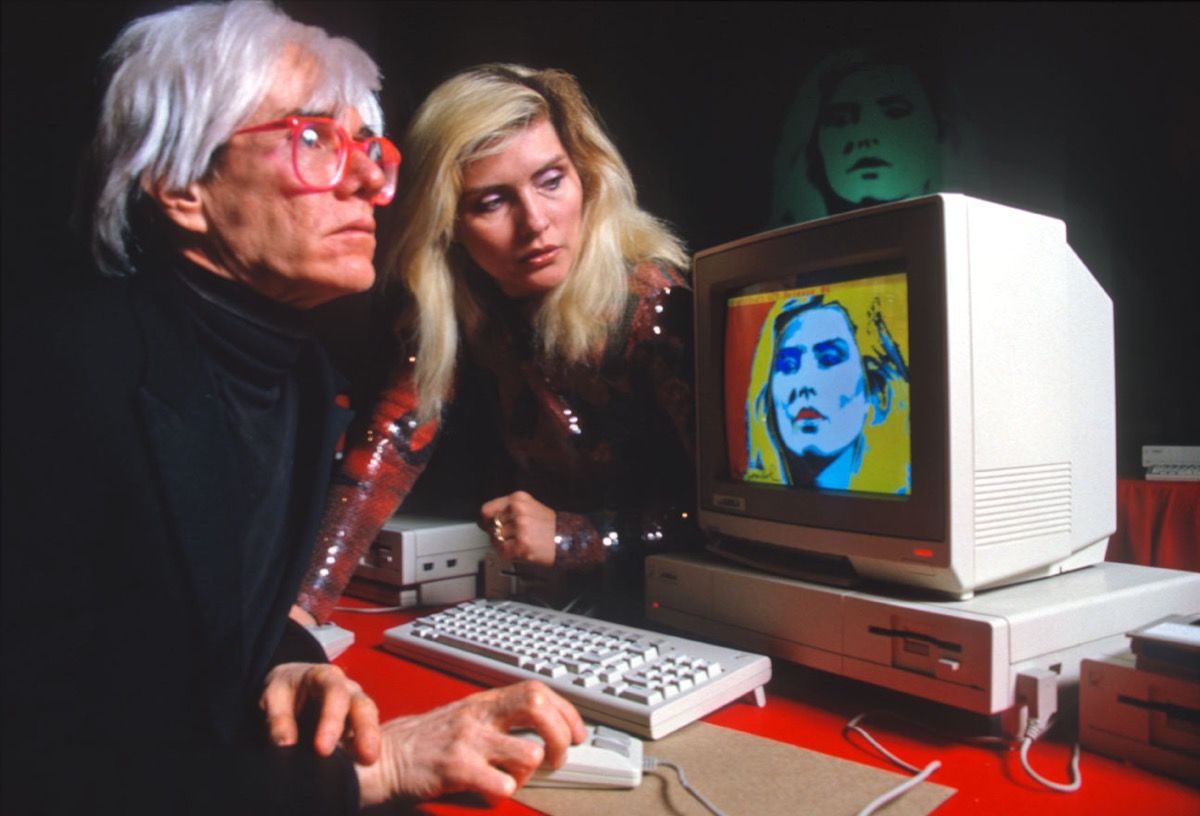

Simultaneously, the possibility of greater expression has roots in freedom, so within the brutality of history, moments of divine inspiration have occurred, possibly through extended peace and periods of abundance. There is now more art being made than ever before, as humans have access to tools of creation like never before. The color blue used to be a symbol of immense wealth. Now we can buy it by the gallon.

“My work isn’t intended to be religious in its theme, but more to express the possibility of there being more to the universe than we can perceive with our senses.”

Buddhism is an interesting one. Their recruitment tools are more elegant and sophisticated, but they have recruitment. It is interesting to consider who they are appealing to. The aesthetics associated with Buddhism seem to also be universally associated with spirituality and lack the association of power and dominance that has been added to the spiritual or religious expressions of Europe. I’m paying attention to symbols in my work, as I recognize the power they carry.

Stuart Ward, Neptune, 2023

In your work we can see references to cycles of death and rebirth, and the connection between the divine and eternity, that are expressed in a visually attractive form. How would you say these concepts of constant changes and cycles speak to our consumption of cultural products, and of cultural trends?

I try to avoid politics before whisky, but there’s an idea by an awful political theorist that makes a lot of sense when removed from the rest of the context of his work. He said that people should express themselves by what they create, not by what they consume. I think most people’s creative expression comes through consumption. How they dress, the music they listen to, the food they eat. One thing that I’ve noticed that makes me uncomfortable is that sometimes after binging on a bunch of interesting and creative content on social media, I feel like I myself have been participatory in the creative process. This is far from accurate, but the feeling has existed, and I wonder if that non-productive creative moment is the reward for most people?

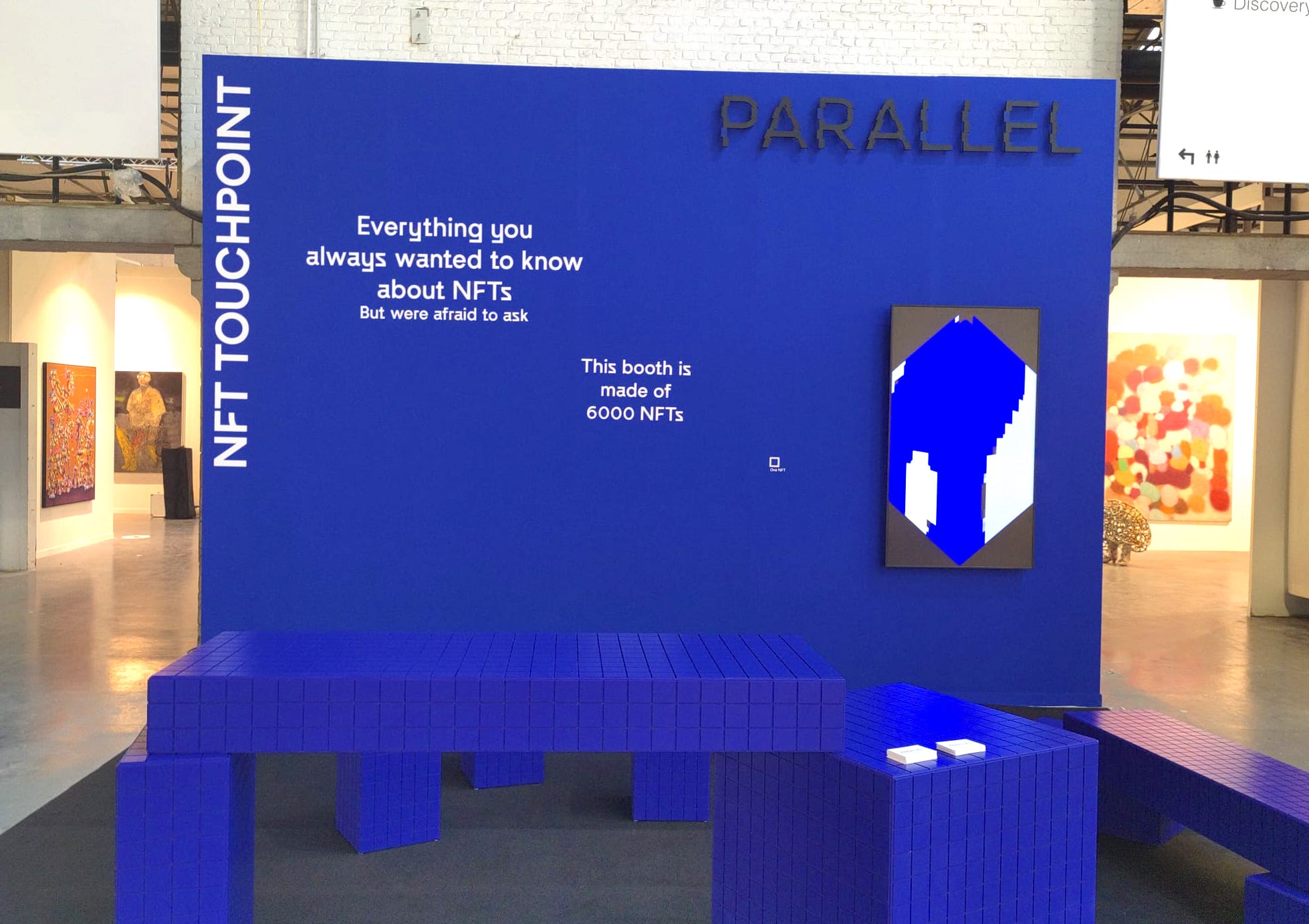

It might also be worth mentioning in the digital art scene, as NFTs emerged, everyone was so excited to break down the existing system and start anew, but within a few months, the existing systems had re-emerged, or the community was unknowingly asking for its return. Curators and critics reappeared. Blue Chip artists in the digital space became a thing. Now the digital scene is an established system waiting for its next interruption.

“As NFTs emerged, everyone was so excited to break down the system and start anew, but within a few months, the existing systems had re-emerged. Now the digital scene is an established system waiting for its next interruption.”

You point out that you are interested in a Neo-Baroque aesthetic and in seeing what is possible to do with decorative forms when their material limitations have been removed. What drove your attention to these decorative forms in the beginning?

Where did these decorative forms emerge from? I know that some forms come from nature, like a dried acanthus leaf, or a fiddlehead fern, but the forms have evolved an almost musical quality. They so beautifully match the music of the era, wherein a form goes one way, and satisfyingly at just the right location, it spins and curls off in a different direction. We like music because it does what we expect, and we like it even more when it does what we didn’t expect, and subsequently brings us back around into what we expect again. Without the restriction of gravity or construction materials, what is the end evolution of those whirling swirling decorative forms? I think the mystery and curiosity to explore those questions drove me towards working with them in my art. That, and my early childhood home had several pieces of furniture with decorative swirls that I’d get lost in while playing, so there may be some deep memories of early childhood surfacing.

Stuart Ward, Artemis, 2023

In the artworks we see on Niio the elements of Baroque architecture create a frame around the main character, but in other works such as Ecstatic Angel and Transformation at the Gates of Eternity, which feature sculptures by Bernini, the architecture dwarfs the sculpture and becomes the main element in the composition. How do you conceive the balance between the two: sculpture and architecture, figure and frame?

Good question. I see them merging to become part of a singular experience where the architectural details and the sculptural details become a cohesive whole. This is part of the effort to explore the forms without physical limits. They can occupy similar values. Beyond that, in the Bernini piece for example, if it were to take a more dominant role in terms of scale in relation to the rest of the artwork, I’d feel a sense of unease. The sculpture is iconic and stands alone as an artwork. Is a great photograph of the sculpture also an artwork? Sure. I guess. But it runs dangerously close to losing its artness and becoming just a photograph. I feel similarly about a 3D rendering of a sculpture. Yes, I posed it in a scene. Yes, I organized a virtual camera, and created a lighting system, and a material system, but it’s still at the edge of art, in my valuation of things. Perhaps my system of values is more strict than others, but I felt like to make the artwork a deeper expression of my own work while simultaneously referring to the greatness of Bernini’s sculpture, the surrounding artwork needed to occupy more space visually and thematically.

“I’m a big fan of magenta. It’s my favourite color, despite not being a color on the electromagnetic spectrum.”

Your choice of colors is quite characteristic of a type of aesthetic that has become popular in NFT communities. Have you been inspired by other creators in these communities? What do the colors bring to these compositions in relation to the references to Greek and Roman sculpture, and Baroque architecture?

My artwork series from 2021 was more ‘classical’ in its color range, in comparison to Baroque artwork. In late 2021 I moved to Tokyo, again. The neon and lights of the big city had an influence on my aesthetic, and the works made in 2022 evolved to have luminous neon shapes and glowing effects. I think part of the purpose of it was to progress in the arms race against creative stagnation, and to challenge myself to express in a new aesthetic.

To further discuss colour for a minute, I’m a big fan of magenta. It’s my favourite color, despite not being a color on the electromagnetic spectrum. I was working with a lighting expert several years ago planning some lighting projections for an event. They told me that using warm colours like orange, yellow, and pink will make the audience under the lights look healthy and the event will be more fun and better received, as opposed to an event lit with too much blue and green, making people look unhealthy. I think of that, and use magenta’s contrasting colors with consideration.

Aqua/teal expands into the possibility of color. Before synthetic pigments arrived on the scene, some colours were rarely available for use. Despite the sky being blue, blue pigments were expensive and rare, as were purples, which is the reason for their association with royalty. The arrival of spring and the blooming of flowers in the pre-synthetic colour era meant that colours would be visible, having almost entirely disappeared to nearly everyone for the winter, the exception being the blue sky, always out of reach. Coincidentally, blue leds were the most difficult coloured lights to engineer: there were a few decades where led screens were yellow, orange, red and green. Now, the entire world can access as much colour as they want without restriction, but perhaps we have a deep memory of life before that unlimited access, and give brightly coloured things a sense of special attention. It could also be linked to an earlier structure of foraging for colourful fruits and berries. The concept is interesting to mentally explore.

“Social media has caused some harm. Artworks are becoming a response to the high speed social feedback rather than taking time to really work on an idea and iterate on the work.”

You speak of creating moments of elation and wonder with your artworks. Would you say that the use of a symmetrical composition, the cyclical movement of the different elements, and the rhythm of the animation are all intended to create a mesmerizing effect?

My work intends to express the possibility of there being more to the universe than we can perceive with our senses. This is generally objectively true in that right now we can’t sense the multitude of wifi and cellular signals flowing through our bodies. But further to that, more deeply universal questions about the possibility of a soul or spirit within, or a sense of divinity. I’m careful with how to express this, because my artwork isn’t intended to be religious in its theme, but more to express a possibility of ‘more’ through myth, pattern, motion, and the emotional response that those tools create. There are two fantastic books, The Oxford Compendium of Optical Illusions, and Vision and Art; The Biology of Seeing. They look into what is happening in the eye and the brain while observing images, and how optical illusions trick our visual sense. I’ve been exploring how to use this in art to express a sense of mystery.

Stuart Ward, Ecstatic Dance 2, 2023

In your opinion, how have social media and motion graphics influenced digital art creators?

Social media has caused some harm. As a result of the trend of Dailies, artists are rushing to create work quickly in order to get something new to share every day. In the process of trying to accomplish that, we end up making simpler things, and exploring creative ideas that we’ve already proven to be a social media hit. So the artwork becomes a response to the high speed social feedback rather than taking time to really work on an idea and iterate on the work. I know, because I fell into the same traps.

I must also confess that a short loop is better for me, because the render time is shorter, and the reward centers are activated sooner in the creative process. Some of my loops are only 4 seconds long, despite seeming much longer due to their seamless quality. As I’ve moved further away from the ‘dailies’ style work, I’m more and more comfortable with longer content where some parts loop quickly while others take more time to reach their looping conclusion. But this is still content under 30s long.

Motion graphics add another tool to the artist’s creative capacity. The addition of motion to artworks adds to the capability of expression, but without proper media systems and hardware, it runs the risk of being forgotten, in favor of more physical media. It’s part of the reason why I’m excited to be working with NIIO: they facilitate the exhibition of motion enabled artwork in a progressive and intelligent way.

“I’m excited to be working with NIIO because they facilitate the exhibition of motion enabled artwork in a progressive and intelligent way.”

Your experience as a VJ and designer have surely taken you through different spheres of the visual arts, crossing the membrane between what is considered art and what is considered popular culture. What is your opinion on this separation? How can it be overcome in an age of art on screens and online distribution?

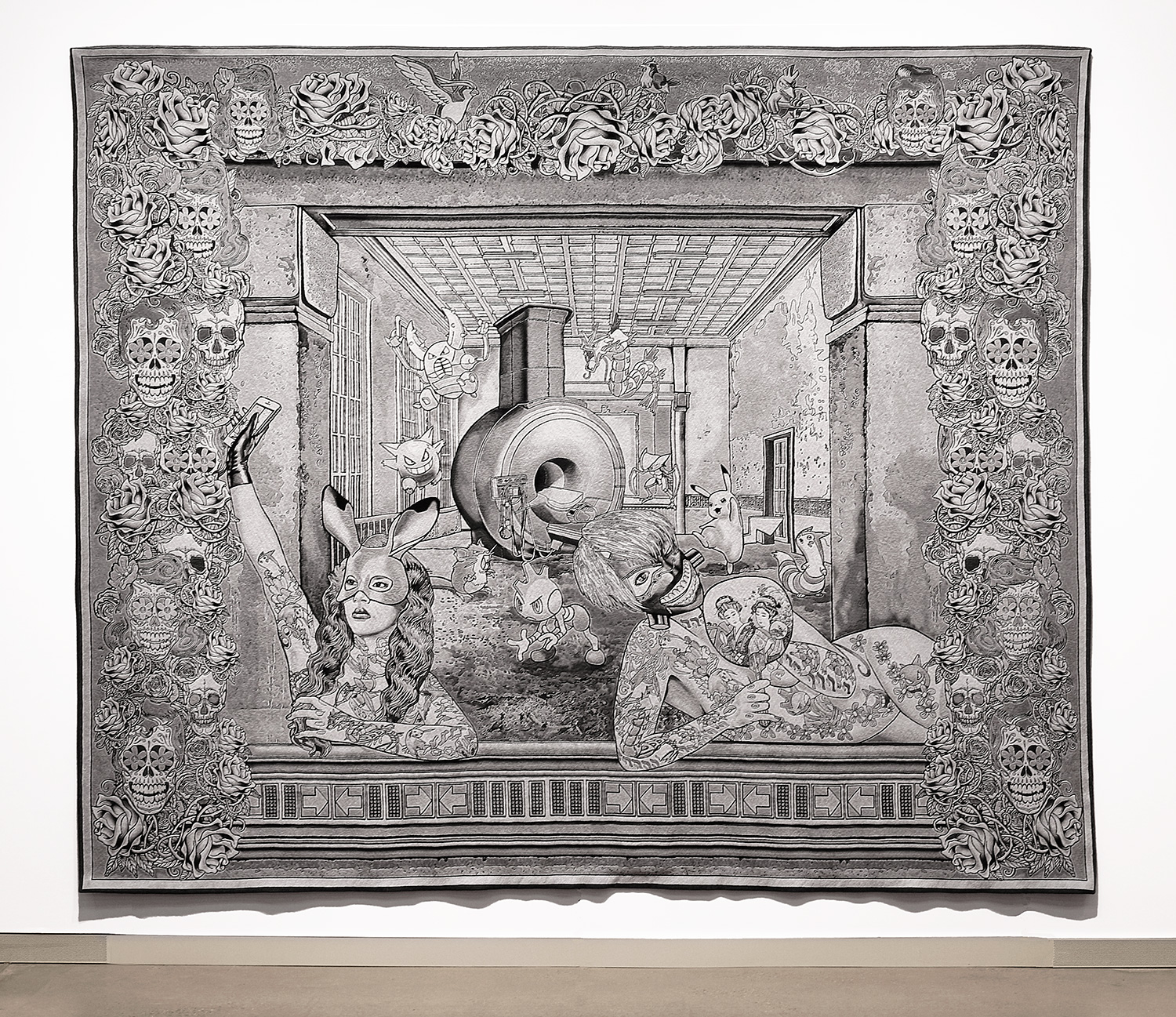

The barrier between art and pop culture has been largely broken down during my art career. Collaborating with a brand used to be considered ‘selling out’ and the only customers and revenue streams an artist should have was sales of art, and the non-art job that supported their practice in the likely event that it wasn’t sufficient. Now we see major artists collaborating with major brands, and it is seen as a part of ‘making it in the art world’.

Stuart Ward, Nymph, 2023

Murakami and Arsham immediately come to mind when it comes to successful collaborations wherein the artist retains control over their image and artwork, while also merging in a beautiful way with well known global brands. Perhaps this process was facilitated by luxury brands supporting the arts, like Fondation Louis Vuitton. The art world seems to have shifted again as NFTs rocketed into the scene. The digital art space was moving so quickly that the old guard couldn’t keep up, and the gatekeepers were left behind. Eventually, in the chaos, a new order emerged, and some artists who were not considered ‘real artists’, but mere ‘digital creators’ found themselves on the inside of the gates, selling work at globally renowned, established art auction houses. The system has restructured.