Pau Waelder

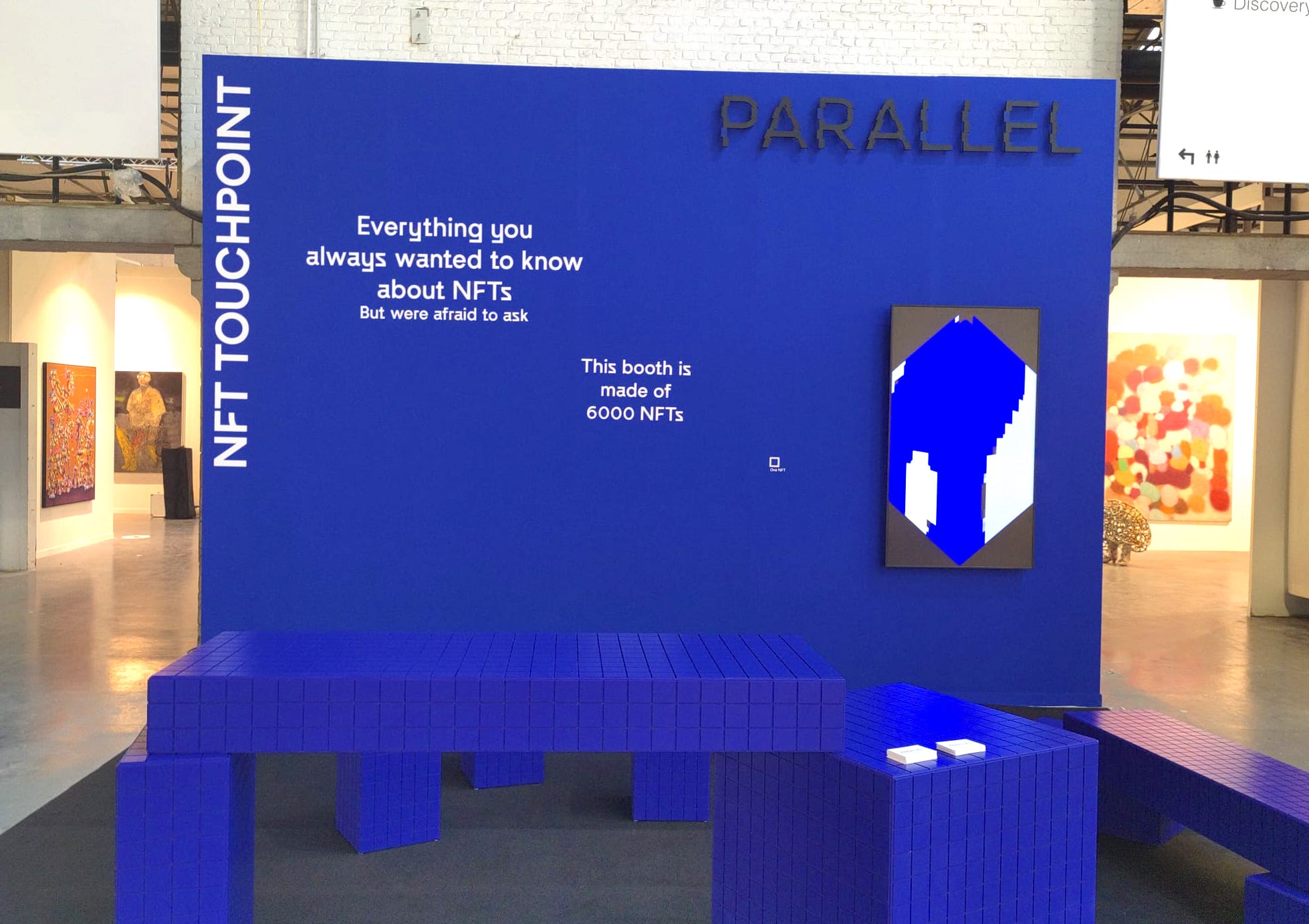

The 38th edition of the Art Brussels art fair, which took place between the 20th and 23rd April, featured for the first time a dedicated space to NFTs and a selection of works sold as non-fungible tokens by participating galleries. This was made possible through a partnership with Parallel, a production and advisory platform dedicated to contemporary art and Web3 technologies. Parallel worked with the galleries to showcase a selection of the NFTs hosted on the online space JPG, a platform that has developed a curatorial protocol for the presentation of this type of artworks. Additionally, Parallel built a booth that served as an information desk, a meeting point for guided visits, and also hosted an augmented reality artwork. To complement this educational task at the art fair, the team also organized a series of talks about NFTs in collaboration with iMAL, the leading New Media Art Center in Brussels.

As a guest to both the talks and the visits to the galleries, I had the opportunity to observe the different forms of presentation of the artworks, some combining an online and physical presence, and to discuss with gallerists and visitors the options that NFTs and blockchain technologies present to collectors of contemporary art.

The galleries

It might be expected that NFTs are mainly sold by young galleries, or those already focused on digital art, but actually the galleries participating in the collaboration between Art Brussels and Parallel are quite different from each other. Veteran galleries with an outstanding record in the contemporary art market Michael Janssen (Berlin) and Nagel Draxler (Cologne, Berlin, Munich), have integrated sales of artworks minted as NFTs, alongside the younger contemporary art galleries The Hole (New York), Plus One (Antwerp), and Office Impart (Berlin), as well as others with a particular focus on local and national art scenes, such as Anca Poterasu (Bucharest), Sapar Contemporary (New York), and Green on Red (Dublin). An exceptional case among them is Galerie Charlot (Paris, Tel Aviv), which has been dedicated to digital art for more than a decade, and consequently presented the booth that most seamlessly integrated the languages of digital and contemporary art.

There were interesting connections and similarities between the different artistic projects presented at the galleries, and for this reason I will focus on these connections rather than list the artworks displayed on each booth.

The lightness and solidity of 3D worlds

Artists Sabrina Ratté (Charlot) and Theo Triantafyllidis (Nagel Draxler) are known for their particular approach to building 3D worlds, the former creating architectural spaces that blend natural and artificial forms bordering abstraction, the latter fully appropriating video game environments and characters to create immersive scenes, some of which are dominated by the presence of a brawny female ork, the artist’s iconic avatar. Their works find a physical presence, in the case of Ratté, in prints that depict a selected view of her imagined worlds, and in Triantafyllidis’ work as an hologram that underscores the illusory aspect of the digital image. Artists Frederik Heyman (Plus One) and Louis-Paul Caron (Charlot), on the other hand, build their virtual worlds with a particular attention to the textures and physical qualities of each element, and while Caron emphasizes the artificiality of his compositions, Heyman skillfully reproduces every detail. Their works, by contrast, have no physical output: they live as images on a screen.

Generative art, back to the roots

In the current NFT market, generative art has become a favorite among artists and collectors due to the possibility of launching a series of works from a single program, each instance of the program being minted as a unique NFT. This allows artists, on the one hand, to create large series that are automatically generated from a single program, and collectors, on the other hand, to own a piece that is unique while also belonging to a series. However, generative art has also been about the artwork being a single program that constantly generates new compositions, ad infinitum. Since the pioneering work of algorithmic artists, this idea has been adopted by numerous artists in very different ways, sometimes as an autopoietic process and others fed by external data. The Net Art Generator (1997), a seminal web-based piece by Cornelia Sollfrank (Office Impart) offers a peculiar example, as it allows users to create a visual composition from a simple query on a search engine. Appropriating the outputs of anonymous users, the artist has minted a series of NFTs from collages of Andy Warhol’s silkscreen prints found online and recomposed by her net art generator program. In a similar vein, Thomas Israël (Charlot) creates an homage to the Dada movement through a collage based on a work by László Moholy-Nagy that is populated by visual elements resulting from automated queries for the term “dada” in an online search engine.

In contrast to Sollfrank’s and Israël’s additive practice, Antoine Schmitt (Charlot) and LIA (Office Impart) create generative artworks that are fully based on the elements of a visual language of their own. Schmitt presents a generative piece based on his War series (2015) that depicts the struggle of Ukrainian forces resisting the invasion of the Russian army. The subject of the artwork is made more inspiring by the fact that the pixels are actually elements following a set of instructions that lead them to perform the scripted action endlessly. LIA’s drawing machine develops a previously written program from which she has generated a series of 100 NFTs that illustrate the vast possibilities of visual composition with minimalistic elements and a set of instructions.

Rules and smart contracts

NFTs are minted through smart contracts, which are sets of agreements or instructions that self-execute on certain actions or when certain conditions are met. For instance, a smart contract will automatically transfer a 10% commission of the sale of an NFT on the secondary market to the artist who created it. But smart contracts can be used for many other purposes, and artists are also exploring the possibilities they bring, alongside generative software, to establish interactions between the artworks and their collectors. Sarah Friend (Nagel Draxler) has created in Life Forms a series of digital entities linked to NFTs. The entities, as designed by the artist, require new caretakers every 90 days, and therefore a collector must transfer the NFT to a new owner before this period has passed in order to keep the entity alive. The artwork thus plays with the tendency to “flip” NFTs that is prevalent among speculators and translates it into a caring, rather than profiting, activity. Artists Kim Asendorf and Jonas Lund (Office Impart) also play with generative pieces that integrate the activity of their collectors. Asendorf has created a series of NFTs and an editor, allowing the owner of the editor to “sabotage” the compositions owned by other collectors. Lund updates a previous web-based artwork which displays the browser window sizes of all users who have accessed it and turns it into a generative abstract piece in which each collector can create their own style and color, and mint their piece until the limited series of 128 has been completed.

Lingua arcana

An interesting aspect of NFTs and blockchain and cryptocurrency artworks is that they bring back the arcane qualities associated with digital technologies that had been dissipated by our frequent use of user-friendly devices and interfaces. Kevin Abosch (Nagel Draxler), one of the artists who addressed blockchain technology in his work some years before the NFT boom, presents a series of artworks that use cryptography to hide information in plain sight and extract from the combinations of letters and numbers a certain compositional quality. Eduardo Kac (Charlot) mints an animation based on a form of writing of his own, inspired by his influential bioart project GFP Bunny (2000). Here, the strings of indecipherable characters run wildly across the space, in a way that reminds of the constant activity on blockchains and seems fit for an NFT. Artist and filmmaker David O’Reilly (Green on Red) explores another aspect of the arcane in computer science by digging out one of the few remaining Intel 4004 CPUs, the first microcontroller to put a full computer in a single chip. This relic of the digital age is placed by the artist inside a block of solid resin, creating a sculpture that brings to mind the aesthetic of classic science fiction films such as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odissey (1968). The sculpture is sold alongside a video of the piece rotating, minted as an NFT and therefore permanently stored in the same digital environment that the chip contributed to create.

Weaving the digital

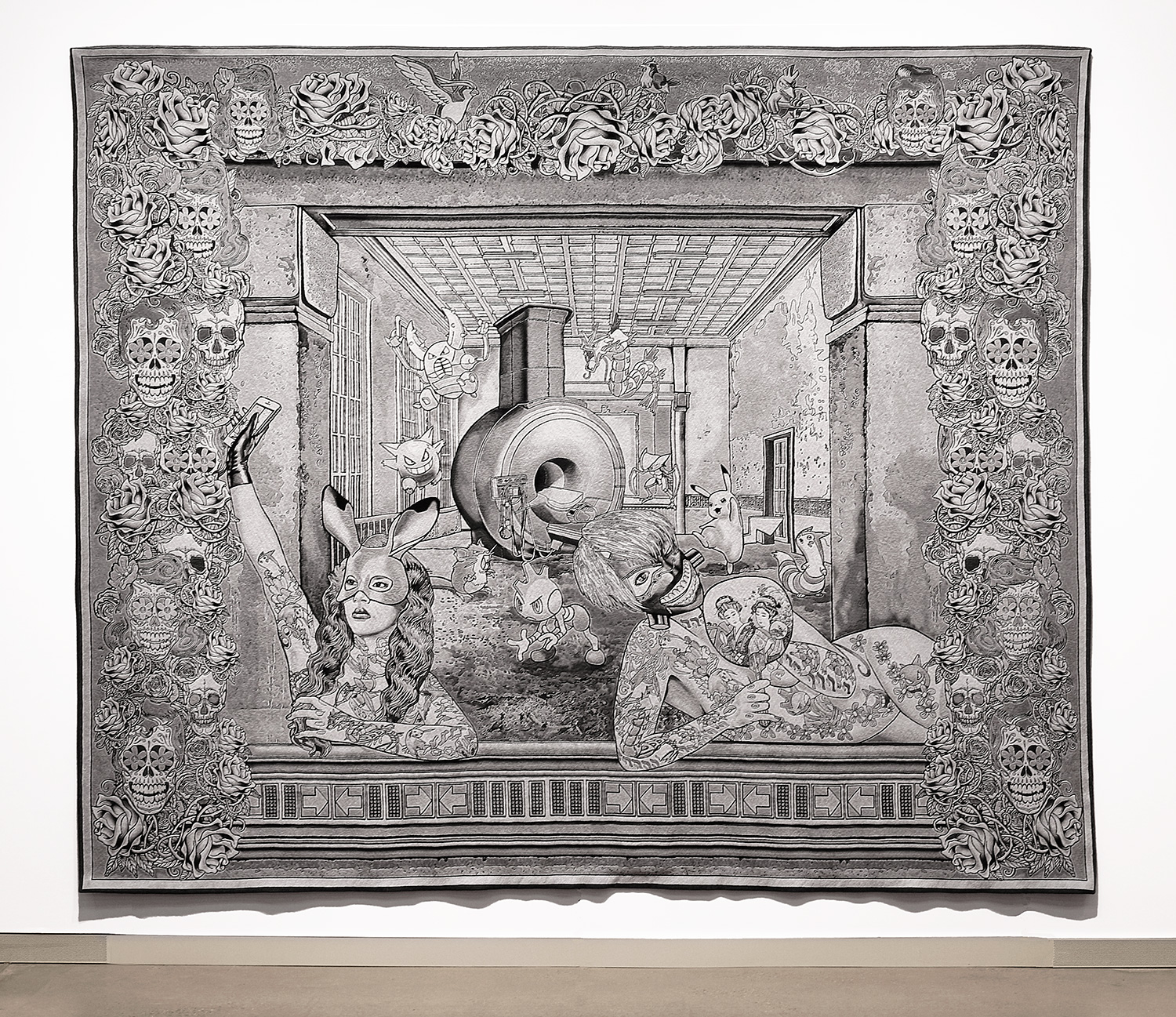

Computing and industrial weaving find a common ancestor in Joseph-Marie Jacquard’s programmable loom from the early 1800s, which inspired mathematician Charles Babbage’s design of the Analytical Engine, a conceptual model for the modern computer, of which fellow mathematician Ada Lovelace was the first programmer. Nowadays, artists who create tapestries usually work on a digital image that is weaved by computer assisted machines evolved from the original Jacquard loom. This direct yet often overlooked connection between computing and weaving gives the resulting artworks a distinct quality, particularly when the tapestry does not intend to imitate a traditional, hand-woven textile, but replicate the complexities of a digital image. Megan Dominescu (Anca Poterasu), Ry David Bradley (The Hole), and Margret Eicher (Michael Janssen) present their work as tapestries that faithfully reproduce their particular visual styles, from Dominescu’s apparently naïve drawings, to Bailey’s deconstructed portraits, and Eicher’s elaborate compositions combining references to art history, the decorative arts, and popular digital culture. Here, the “original” work, akin to the cartoon, is a digital file, and hence minting it as an NFT offers collectors the ownership of the image as it was created by the artist before the production of the tapestry. Some artists may even decide not to produce the tapestry, which in this case would leave the digital image as the only output. In this manner, the NFT points to the origin of the artwork and to the fact that it exists even prior to its materialization in a physical format.

One format to encompass them all

The accelerated growth of the NFT market and the possibilities that minting on a blockchain gives to artists and creatives have understandably led to a growing interest in translating artworks in other formats into images than can be assigned a non-fungible token. Artists Victor Verhelst and Beni Bischof (Plus One), Chun Hua Catherine Dong (Charlot), Stepan Ryabchenko and WAONE (Sapar Contemporary), whose work is respectively linked to graphic design, collage, performance, video installation, and mural painting, but who, as most artists nowadays, also work primarily with digital images, have integrated NFTs into their practice. The minted artworks become in this case an extension of a work that exists in other formats but finds a way to be distributed and collected online.

A look at the NFT offerings in the context of the galleries participating in Art Brussels provides a telling picture of the progressive integration of NFTs in the regular operations of the contemporary art market. Certainly, they are still a curiosity for most visitors and they raise many doubts, but the way in which they have become part of the work of some artists, one year into the NFT boom, indicates that the creators and their galleries have understood the possibilities provided by non-fungible tokens. As standalone digital artworks or combined with physical objects, NFTs in the context of professional contemporary art galleries seem on track to overcome the hype and contribute to expanding the forms of collecting digital art.