Pau Waelder

Polina Bulgakova is a digital 3D artist who has developed her practice since 2020. Working in the “surrealistic realism” style, Polina crafts visual narratives that challenge the constraints of real-world physics, inviting audiences to think beyond conventional limits and embrace the possibility that anything is achievable. Originally from Siberia and now based in Israel, Polina draws inspiration from the cultural contrasts she has experienced, integrating these influences into her work to create striking visual juxtapositions. Her expertise spans product visualizations, vision boards, and concept art in both static and motion formats.

Following her solo artcast Dreamlands on Niio, Polina Bulgakova elaborates on her practice and background in the following interview.

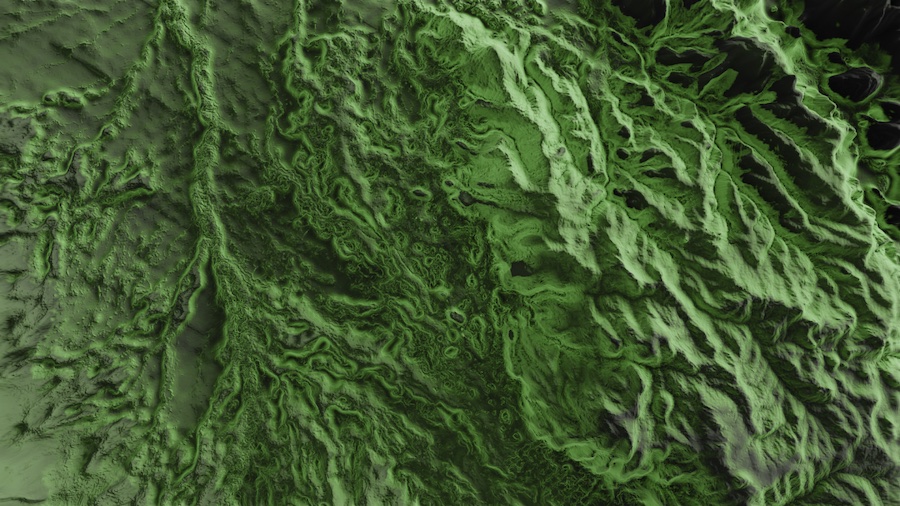

Polina Bulgakova. Sleep Tight, 2021

You were raised in Siberia but now live in Israel. How have your life experiences and cultural background influenced your work?

It made my work very authentic and honest. I learnt how to embrace my differences and diversity, I learnt that it is ok to not fit fully and that my art can not fit to any defined style or niche. I realized that my art is a reflection of what is going on in my life, a reflection of my reactions to the environment or nostalgia, and the only way to be honest in my work is to actually be honest about who I am.

“My art is a reflection of what is going on in my life, and the only way to be honest in my work is to actually be honest about who I am.”

While having a background in more traditional forms of art making, you have found your medium of expression in 3D rendering and animation. Can you tell us a bit about the path that led to digital creation?

Before moving to Israel, my main medium was oil and a little watercolors, but a good part of my income was selling my oil paintings and oil commissions. Once I moved to Israel in 2017, I didn’t have proper space for that – oil is smelly and dirty, and I had to move to digital 2D. For 2 years I was painting in Photoshop, but it felt like something was missing, it felt like something flat – after you work with oil with bold texture, it was not “it”. In 2019 I moved to work from home due to COVID, and decided to learn something new, which was 3D. I fell in love instantly, and since then it hasn’t changed. I sometimes mix 2D and 2D, but both digital. Now if I take a real brush – it’s only for relaxation or if I want to fill a wall at my home.

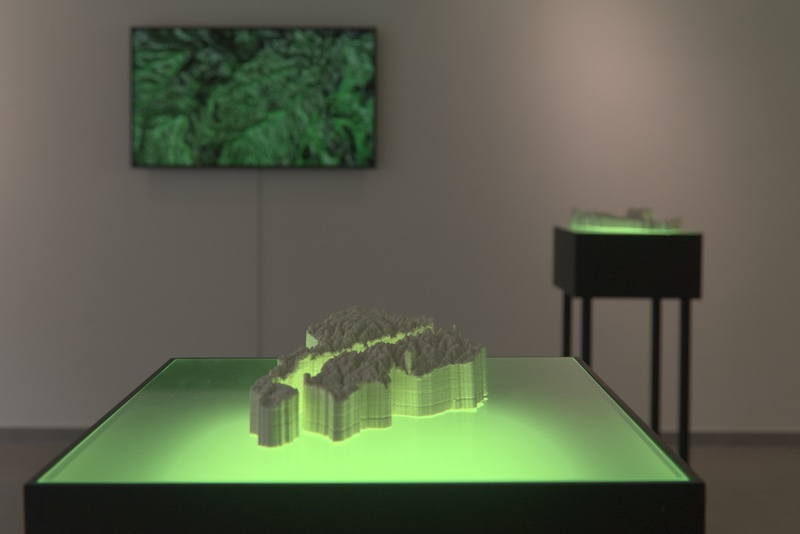

Polina Bulgakova. Seated, 2024

You combine your artistic projects with professional 3D rendering and creative services such as product visualization and 3D models. How do your commissioned work and art projects influence each other?

There is a bold connection between those two. Commissions sometimes can be challenging, and sometimes I need to learn new techniques quickly to finish the work on time. But once I explore something new, it’s like a game with new levels – it sparks my curiosity, and I dive deeper into it in my art projects. And sometimes it’s the opposite – I find/learn something new that can be super useful in commissions and use it after I gave it a try in my personal projects.

“This is why I fell in love with 3D so quickly –there are literally no limits.”

An interesting type of commissioned work that you do are Custom Vision Boards, personalized scenes that you render in 3D from a brief that you send to your clients. Can you tell us more about these vision boards and your experience creating them?

I love making Vision Boards, it’s probably my favorite kind of commission. The first one I made for myself a few years ago – I read a lot about that stuff and thought “why don’t I use my favorite tools to make something that will help me reach my goals?”, and I had so much joy and fun making it. Then I started to commission VBs. It’s honestly a pure joy – to get to know a person, their dreams and desires, to see their eyes glowing while they describe their dream life, and then actually visualize it. It’s like a puzzle – I have specific pieces I need to arrange together to get a clear picture, while having certain creative freedom.

Your work is characterized by a photorealistic surrealism that you achieve using 3D animation. What do you find most interesting about the tension between fantasy and reality? In terms of optimizing the work involved and computer processing requirements, do you have some “visual tricks” you can play with?

The most interesting thing about balancing fantasy and reality is that there are no limits and no boundaries at all. I have my patterns, of course, but in terms of the tech side mostly. And this is why I fell in love with 3D so quickly –there are literally no limits. Whatever I have in mind, the craziest ideas I can visualize. Sometimes I mix 2D and 3D, sometimes I animate textures in third party software in order to reduce render time, sometimes I combine those two.

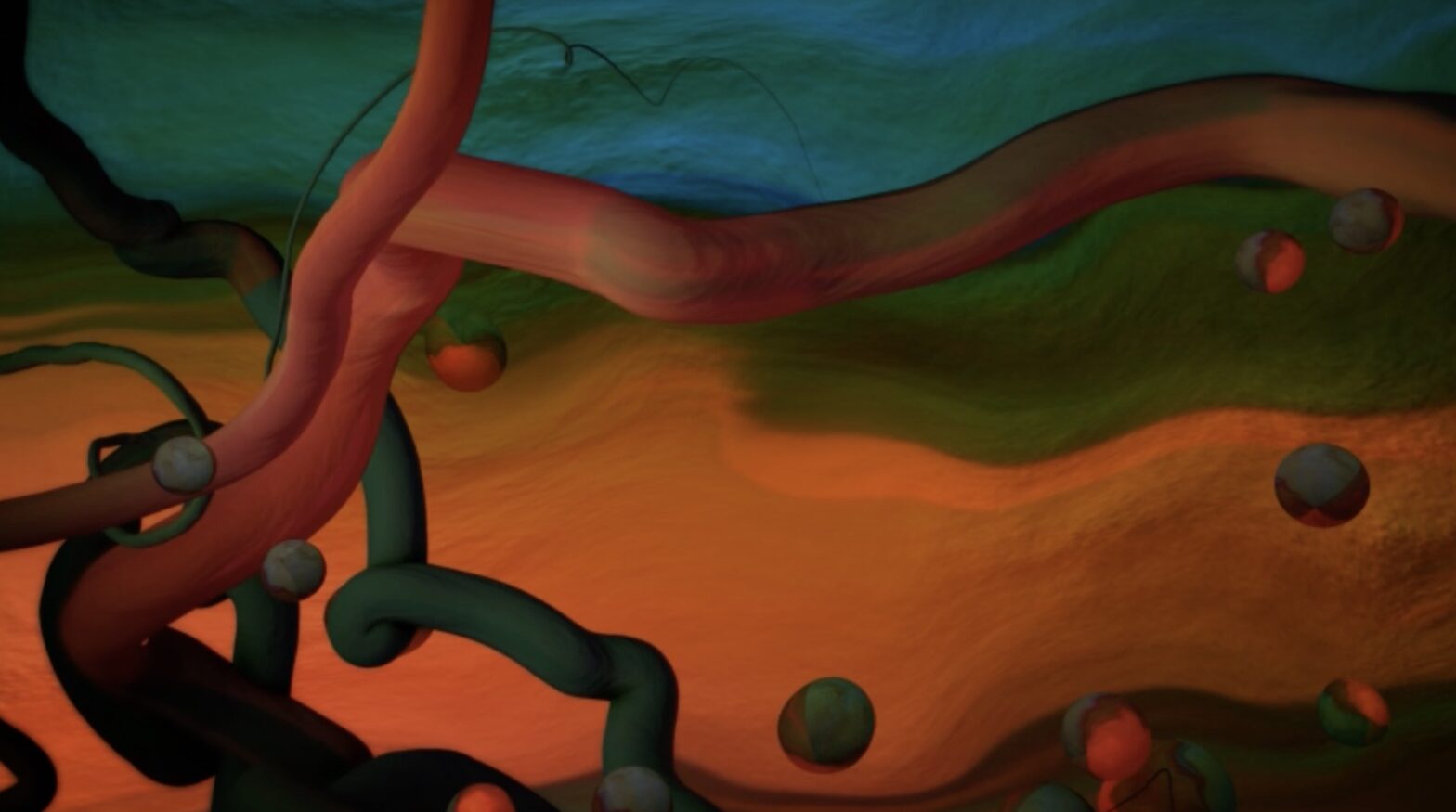

Polina Bulgakova. Witchy Morning, 2022

The artworks we have presented in the artcast “Dreamlands” on Niio not only create imaginary scenes, but also evoke underlying feelings with which we can identify. What inspired you to work with these feelings in dreamlike scenarios, and how do you think they can convey their message to viewers?

“Dreamlands” is probably one of the most honest works of mine. I try to be as authentic as possible in my work, and these kinds of dreamlike scenes are pure reflections of what I was feeling and going through at these times. I hope that every viewer will get the message he or she actually wants to get – be it to reflect on the self, to embrace simple things in daily life, to feel alone but not lonely. My main goal is to encourage people to embrace their authenticity and their differences while looking at my art.

“My work can be viewed as a life graph – you can see what I was going through, and how it influenced me.”

It can be argued that your work is more painterly than cinematic, with peaceful, mediative scenes dominated by a single point of view and a carefully constructed composition. Would you agree with this statement? Do you see digital art as an evolution from the tradition of painting into a new form of creating images meant to be contemplated?

I have works that are dark and moody, works that are chaotic and rhythmic, works that are odd and evoke mixed feelings. It can be viewed as a life graph – depending on the period, you can see what I was going through, and how it influenced my work. The fact that during the last 1-2 years my works are mostly peaceful and calm shows that I’m pretty much in a stable calm period right now.

I don’t think that digital art is an evolution from traditional art. I think it’s a new tool, like a new set of brushes or a new kind of canvas. In the right hands of the right creator, everything can be used to embrace either revolution or traditions, there are artists that combine digital and traditional art tools and create breathtaking pieces.

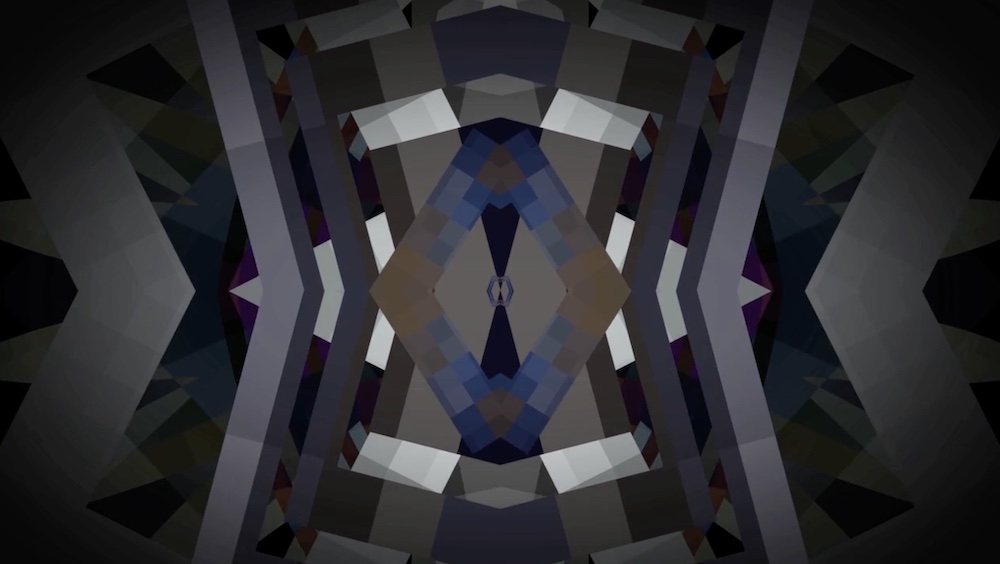

Polina Bulgakova. Wood Morning, 2021

Your work is now available in several online platforms, including Niio. What opportunities do you see in these platforms, and what features do you find (or would like to find) in them that are most convenient for you as a digital artist?

Everyone knows how to make an income from traditional art – you sell an art piece from your shop or gallery, you get paid, you ship it, and you have a happy client. For digital art, especially animations, it’s different. From one side, we have this huge market on social media and the internet that we use to showcase our works, but from the other side – it’s not as simple to sell it as there’s nothing to pack and ship. Platforms like Niio provide us with an amazing opportunity to monetize digital art through licensing and digital editions, and it’s amazing to know your work is appreciated and displayed in someone’s home, office, building etc. I really like the way it gives me both exposure and profit. It can be argued for ages that “a true artist should only care for making great art”, but the truth is everybody needs to feed their family and pay the bills, even artists.

“Platforms like Niio provide us with an amazing opportunity to monetize digital art through licensing and digital editions, and it’s amazing to know your work is appreciated and displayed in someone’s home, office, or building.”