Roxanne Vardi

Matteo Zamagni is a multi-disciplinary artist who works across the visual arts, electronic music, multimedia installations, and film production. Using analytical geoscientific tools, VR/AR/MR, real-time generative imaging, photogrammetry, and CGI techniques Zamagni explores the complexities of the different crises that define our contemporary age and society. Zamagni’s artistic production is characterized by the exposure of the interrelations between nature and technology through machine-driven visual artworks.

Matteo Zamagni is represented by Gazelli Art House, and has exhibited works at international exhibitions and festivals such as the Barbican Centre, V&A Digital Futures, and Torino Film Festival. In conjunction with the release of Matteo Zamagni’s artcast on Niio titled Experiences of Synchrony we spoke with him about his artistic practice, and his work on the project titled “Unison” for Paraadiso, the new audiovisual collaborative project from producer TSVI, and visual artist and producer Seven Orbits. The audio-visual artworks included in this artcast induce altered states by presenting works which are played out as hypnotic journeys of sound and visuals.

Many of your video works include a sound element as a fundamental focal point. Could you please elaborate on your ongoing exploration of combining the visual and the auditory?

Music has always been a driving force for my works since a very early stage; over the years I have been working with many musicians and producers collaborating on music videos, short films, live visuals and installations, and more recently after delving into music production myself I began exploring real-time audio-visual experiences through the following projects ‘seven orbits’ and ‘Paraadiso’ which were released on Shanghai-based record label SVBKVLT. Through these projects I wanted to develop a tool that seamlessly connected Film, CGI and Audio into a real-time, audio-reactive and interactive environment, where logic systems connect and bridge communication between multiple softwares, informing one another. The project Paraadiso, created in collaboration with TSVI marks the first goal towards the realization of such a tool. This system is autonomous yet can function alongside user input, in this sense, it combines light and sound together using an ecosystem of softwares that enables seamless communication and interaction between the 3D/2D environment and the soundscapes. This approach opens up a sea of possibilities in the creation of real-time video and 3D-based content fully synchronized and triggered via sound, resulting in highly dynamic, ever-changing works. Moreover I can see a lot of potential in creating highly stimulating works which could lead the viewer into deeper states of consciousness.

In the near future, I’m hoping to expand this body of work into a 1-hour long CGI film combining my music production as seven orbits together with CGI shots created inside a game engine.

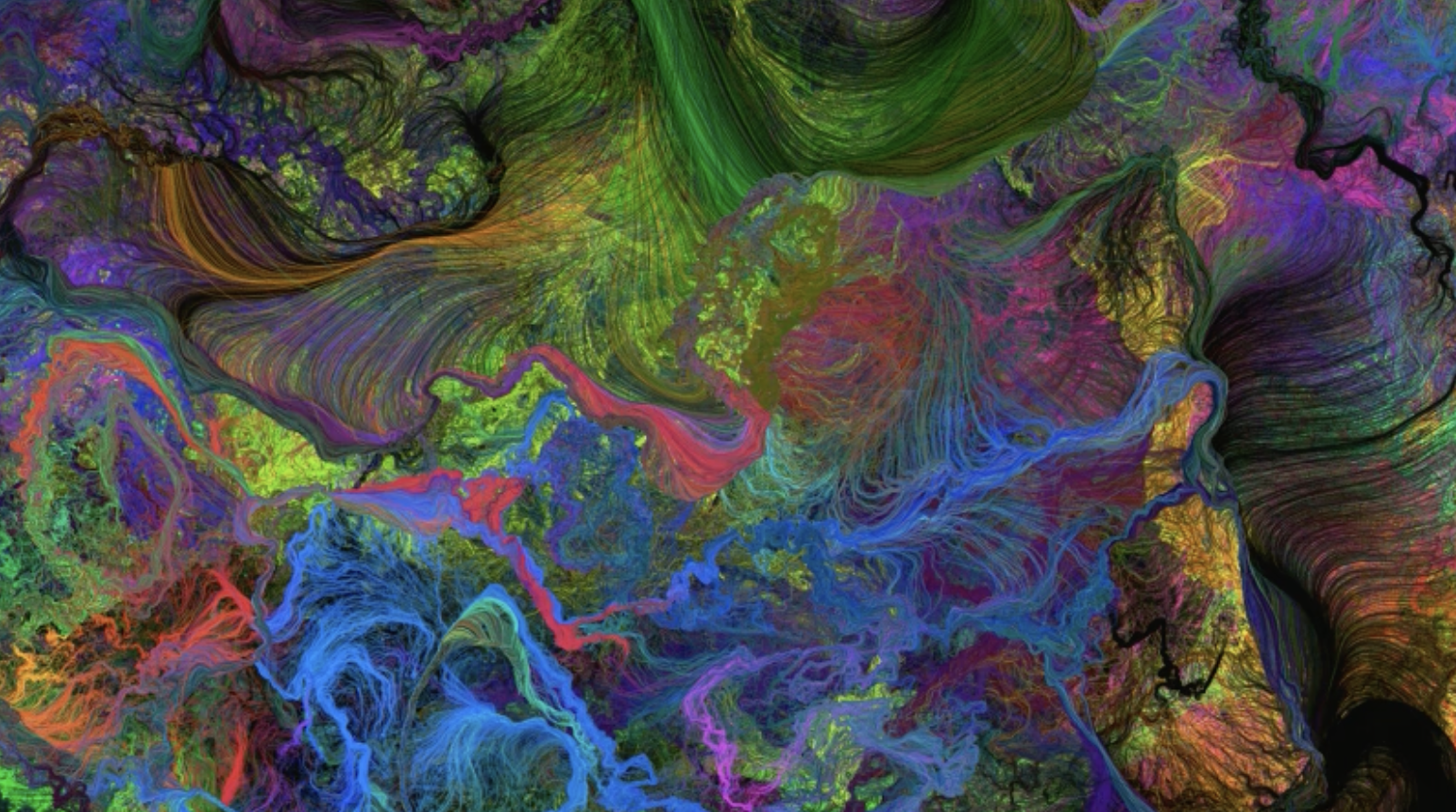

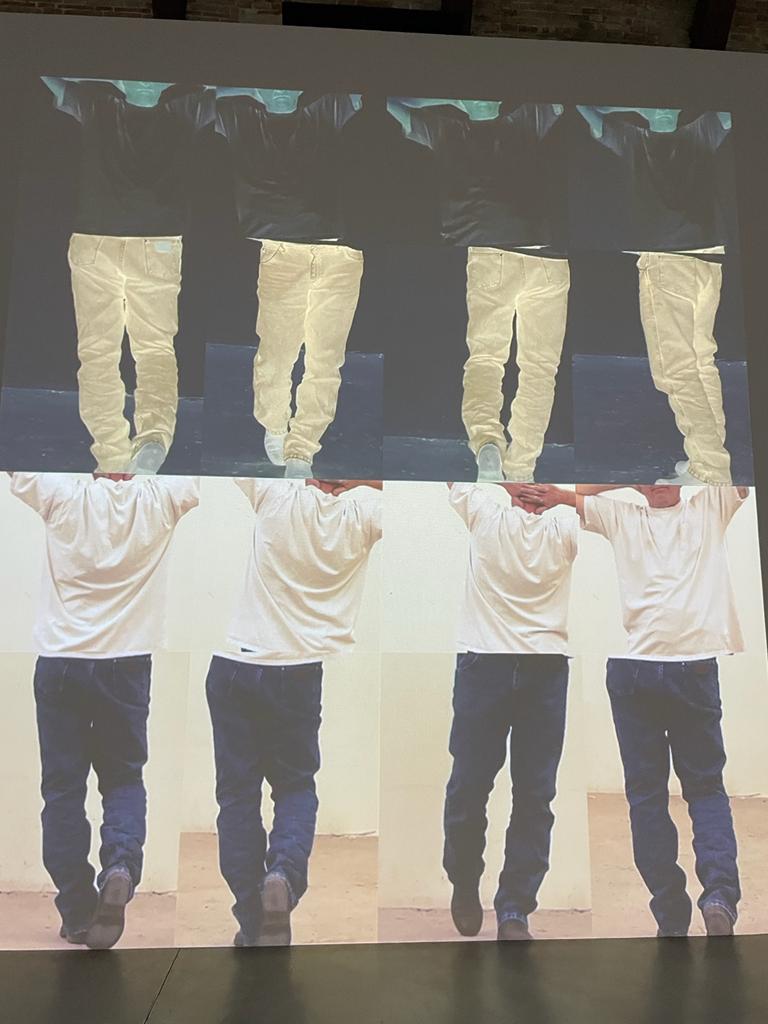

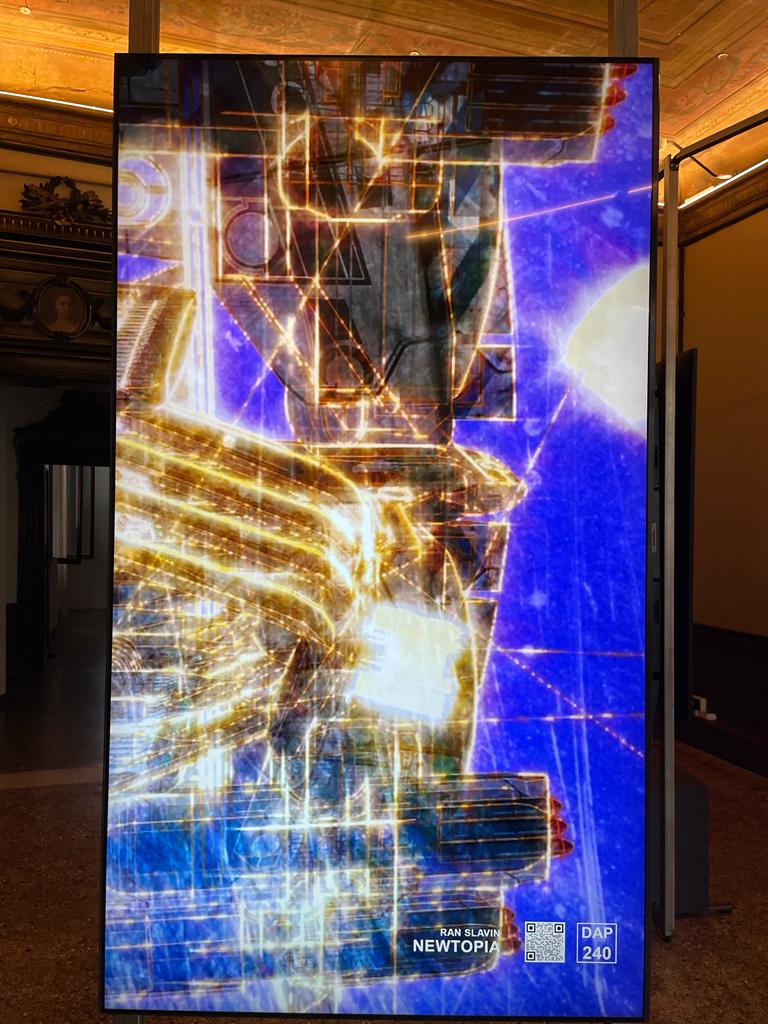

Matteo Zamagni, Unison – 02, 2022.

As the title suggests, your audiovisual collaborative project Unison, aims to create a communal energy as a collective physical experience. What is it that you would like your viewers to gain from this experience?

While we were making the album we were fascinated by how the combination of light and sound in a space would influence the people inside of it; heightening the senses and sometimes, given the right circumstances, conveying a sense of relatedness and care for one another. Human interaction is profoundly social, our everyday life does not take place in isolation but constantly requires our engagement with other people. This feeling of relatedness, reciprocal care and collectivity, is rare and not normally experienced on a day-to day basis especially among strangers and in big cities; The Project Unison references sacred functions and rituals by indigenous populations globally. In ceremonies, it is common to find elements of sound, light, dance and singing which would sometimes throw people into a heightened state of consciousness, sometimes even transcendental. There’s also a strong sense of community and interrelatedness felt within those groups, not only between humans but across the living kingdom, including other animals, plants, biomes and the cosmos.

Many of your artworks are created through a combination of different imaging tools and techniques such as AR, generative imaging, CGI techniques, analytical geoscientific tools and many more? Could you walk us through this complex working process of bringing these elements together into one final piece?

Since I have been quite fluid from an early age I naturally developed a diverse toolset which I reflected in my approach to navigating my diverse interests. Working with technology has deepened my knowledge and skillset by granting me access to accessible tools and resources that could be applied to a wide range of outputs spanning across augmented, virtual and mixed reality to projection mapping, live visuals, virtual production, Interactive Installations, and traditional screen-based work. The creation of a work in my case, is usually aided, informed and mediated by technology; As initial ideas start to materialize they morph and shift based on the environment they’re being developed in.

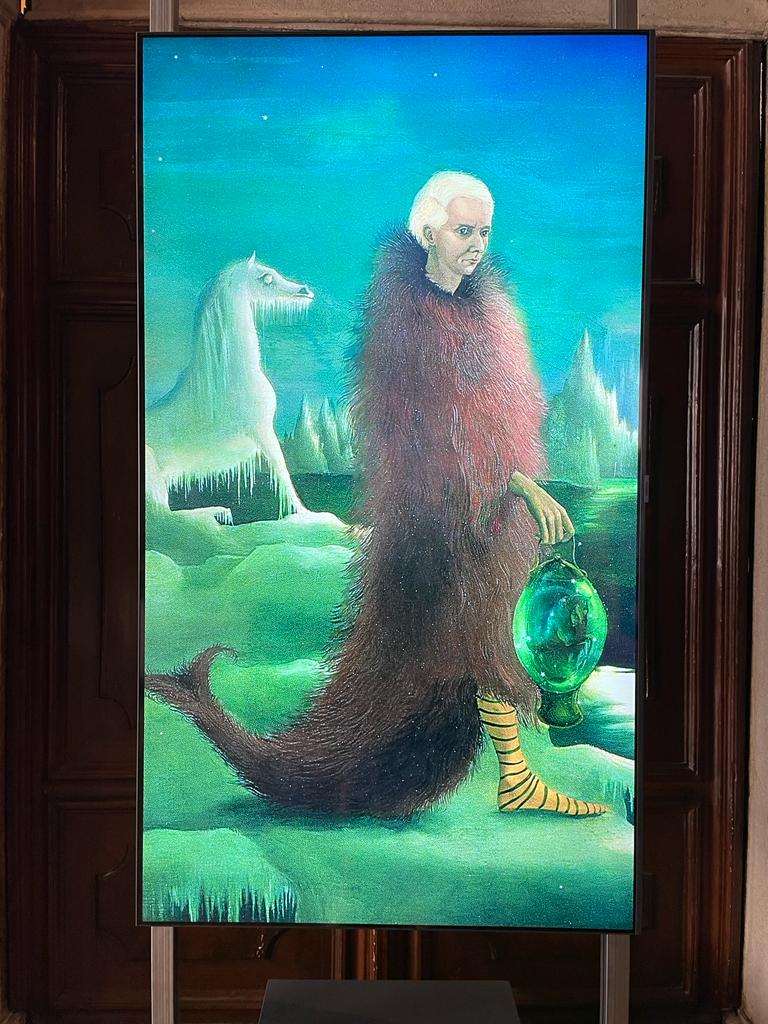

Matteo Zamagni, Unison – 06, 2022.

You have stated that you would like your works to contribute meaningfully to the broader field of environmental activism. In your opinion, what is it about the use of digital tools that can assist us in critically exploring complex planetary issues?

I am incredibly fascinated by the crossover of tools from computer graphics with forensic investigation or geoscientific surveys. Nowadays thanks to the accessibility of software for physics simulations of fluids, sounds, rigid bodies coupled with photogrammetry 3D reconstructions, and publicly available databases online the tools that are commonly used in a VFX pipeline can be ported into a forensic investigative studio. To critically and methodically reconstruct events of various types: from climate-related disasters to cases of social injustice. Inversely you could use geoscientific tools normally used in scientific surveys as a base to develop creative ideas.

Further along this line lies the combination of the ever-increasing power of GPUs (hardware initially designed for CGI) coupled with AI and machine learning, bringing unimaginable leaps forwards in virtually every existing industry but especially crucial in tackling the ecological crisis. What used to take years to simulate now takes minutes.

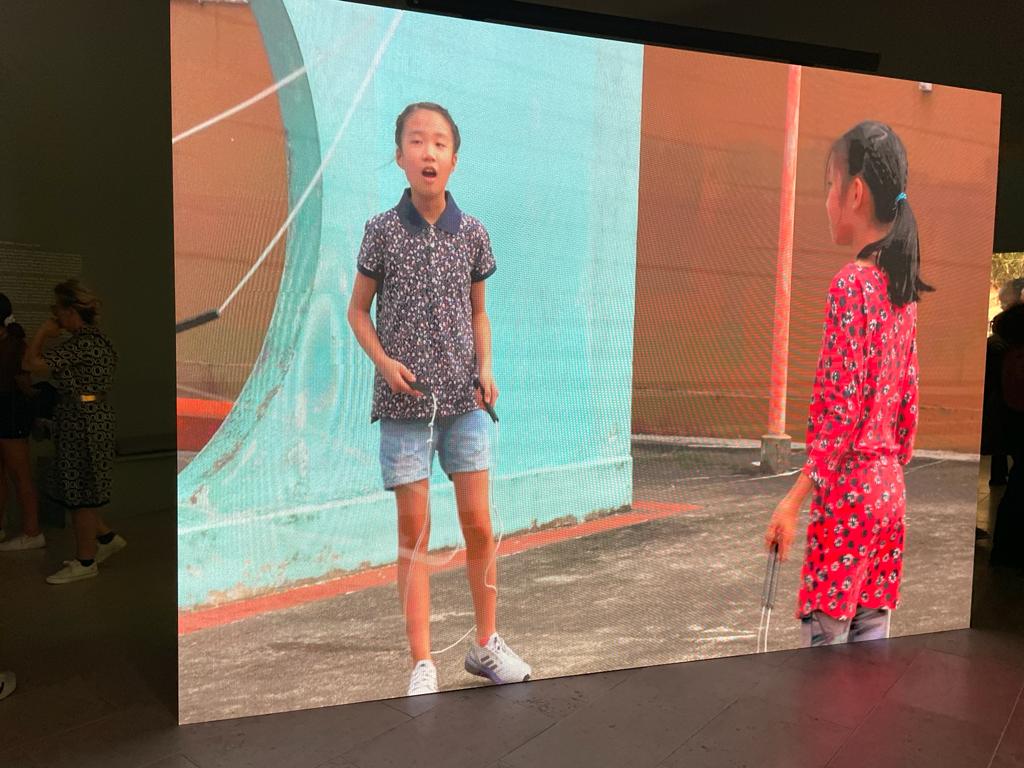

Matteo Zamagni, Unison – 01, 2022.

Many of the sound elements in your works resemble alterations of microscopic sounds which would be heard out in nature such as a caterpillar cracking out of its cocoon. How are these sounds accumulated?

It’s funny that you mention this, it probably came out completely unconsciously. This reminds me of foley recording, a technique used in cinema to recreate the sound of things as well as SFX by recording the sounds of seemingly unrelated objects which allude to the original sound. I can see some similarities between foley and the creation of sounds in our album; Even though we mostly created the sounds digitally rather than physically. Our sample library consists of various techniques spanning digital synthesizers, granular synthesis, and distorted samples.