Roxanne Vardi and Pau Waelder

A multifaceted artist, Yoshi Sodeoka creates a wide range of audiovisual artistic works that include video art, animated gifs, music videos, and editorial illustrations. Influenced from an early stage in his career in noise music and glitch art, as well as avant garde movements such as Op Art, his work is characterized by breaking down the structure of the musical score and visual integrity of the image to find new forms of artistic expression.

A multifaceted artist, Yoshi Sodeoka creates a wide range of audiovisual artistic works that include video art, animated gifs, music videos, and editorial illustrations. Influenced from an early stage in his career in noise music and glitch art, as well as avant garde movements such as Op Art, his work is characterized by breaking down the structure of the musical score and visual integrity of the image to find new forms of artistic expression. His projects, developed individually or in close collaboration with other artists, materialize in fields as diverse as music (Psychic TV, Tame Impala, Oneohtrix Point Never, Beck, The Presets, Max Cooper), illustration (New York Times, Wired, The Atlantic, M.I.T Technology Review) fashion (Adidas, Nike), and advertising (Apple, Samsung). His work has been exhibited internationally, including at Centre Pompidou, Tate Britain, the Museum of Modern Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art, Deitch Projects, La Gaîté Lyrique, the Museum of Moving Image, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and Laforet Museum Harajuku.

In the following conversation, Sodeoka discusses his work and influences, focusing on the two artworks from the series Synthetic Liquid recently commissioned by Niio.

Could you elaborate on how your background in music influences your artistic practice when creating new media artworks?

At the beginning of my abstract video art projects, music and sounds usually come first. I guess in a way, I’m trying to be a human audio visualizer. I usually start by picking up some interesting sounds that I want to work with. That could either come from a friend or from myself. It really depends on how I feel. I’ve been a long time user of Logic (a MIDI sequencer software) so I usually cook up something quick in that. I’ve always played electric guitar since a young age, and I still have a collection of synthesizers and instruments. I’ve been a big fan of experimental noise and ambient music. I am lucky to have some really talented music friends that provide me with the exact sounds I’m looking for if I’m not in the mood to do my own. Anyhow, then I would try to come up with the idea of what sort of visuals go well with that sound. Experimental/Noise music is just a perfect fit with the videos I make.

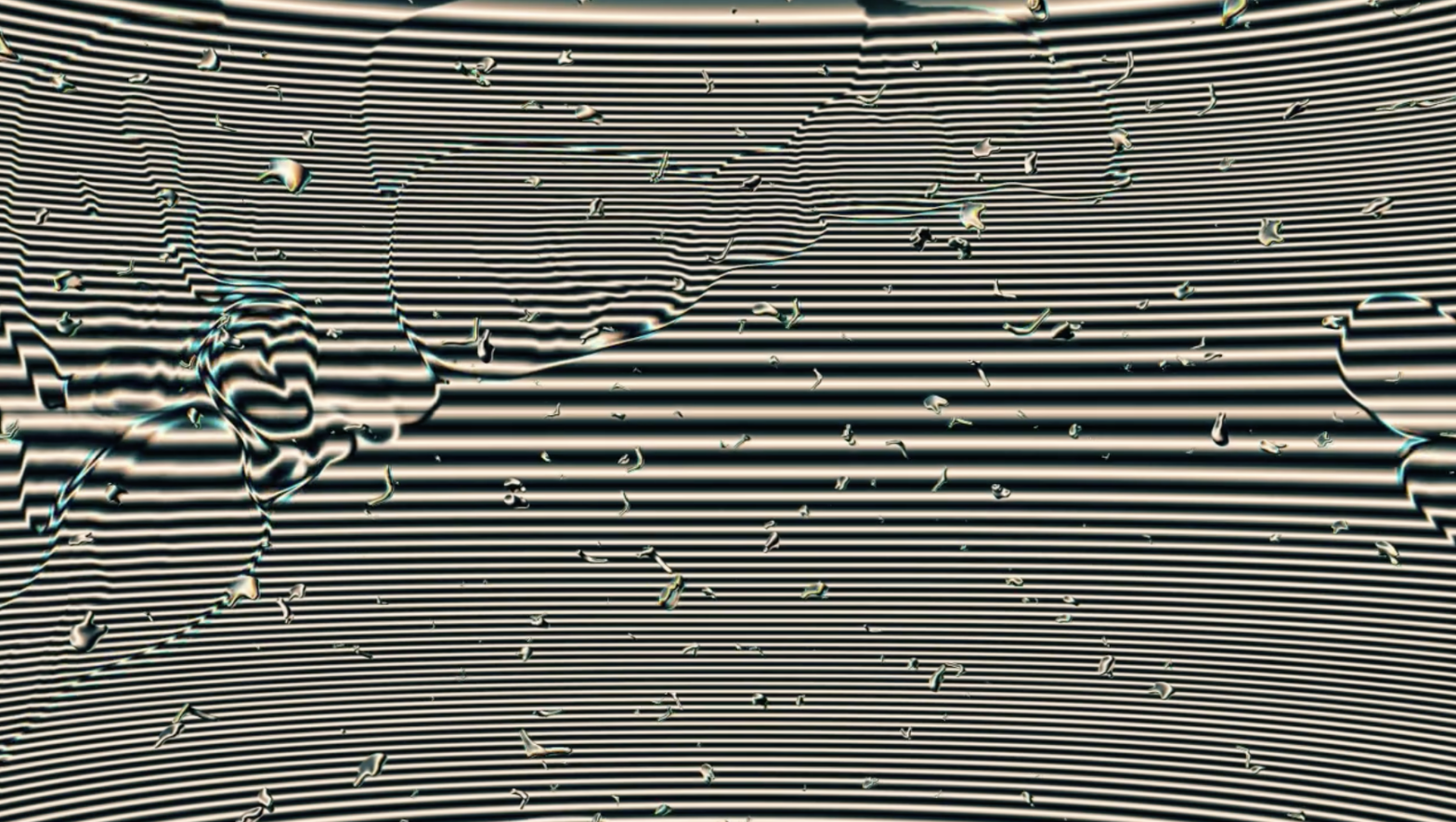

Yoshi Sodeoka, Synthetic Liquid 7, 2022.

Why are you interested in glitch and noise?

I feel that everything is broken anyway, nothing is complete. In computer glitches, something interesting happens, in terms of color and composition. I am mainly interested in these colors and shapes. For me it comes from an aesthetic reason, I am not a conceptual glitch artist. I use it for everything.

However, these particular artworks I created for the commission look more organized, with more neutral colors. It relates to how I feel about the project or what influences me at a particular time, but I really can’t tell why.

“If you depend on the programs and machines you are using, then your creative process becomes shaped by the vision of the person who made that software or those machines.”

The neo-psychedelic style of both commissioned works from your Synthetic Liquid series with its kaleidoscope of colors resembles the aesthetic used by Futurist artists in the early twentieth century, and you have also mentioned your interest in Op Art. Would you say your work relates to these avant garde movements?

Yes, to some certain extent. I like Futurism, particularly in its more abstract manifestations. And in this particular work that I’m presenting in Niio, I should say I’ve been more influenced by Op art. I like the work of Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely, among others. I just like the idea of making video versions of Op art. I enjoy seeing those visual triggers: Op Art makes you question what you are seeing. The arrangement of colors and shapes make your brain think. I like the idea of trying to make animated Op Art, because when you see it your mind goes someplace else, and this is fascinating to me. When you look at a landscape, for instance, you feel calm, whereas with Op Art there is a different feeling.

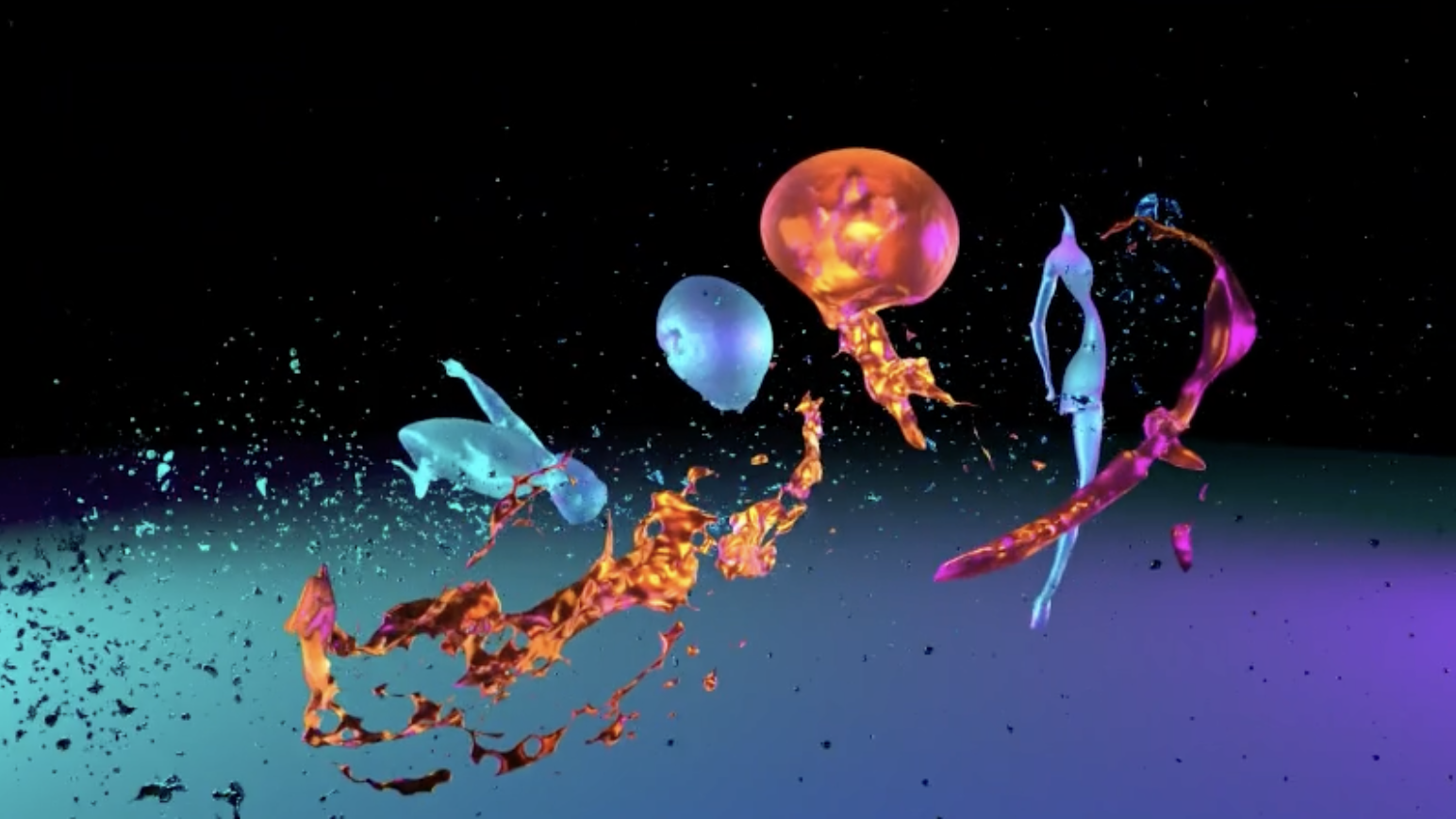

Yoshi Sodeoka, Synthetic Liquid 8, 2022.

Can you tell us about your artistic process and about the different digital softwares that you use in the creation of your video works and the process of moving from analog practices to digital practices?

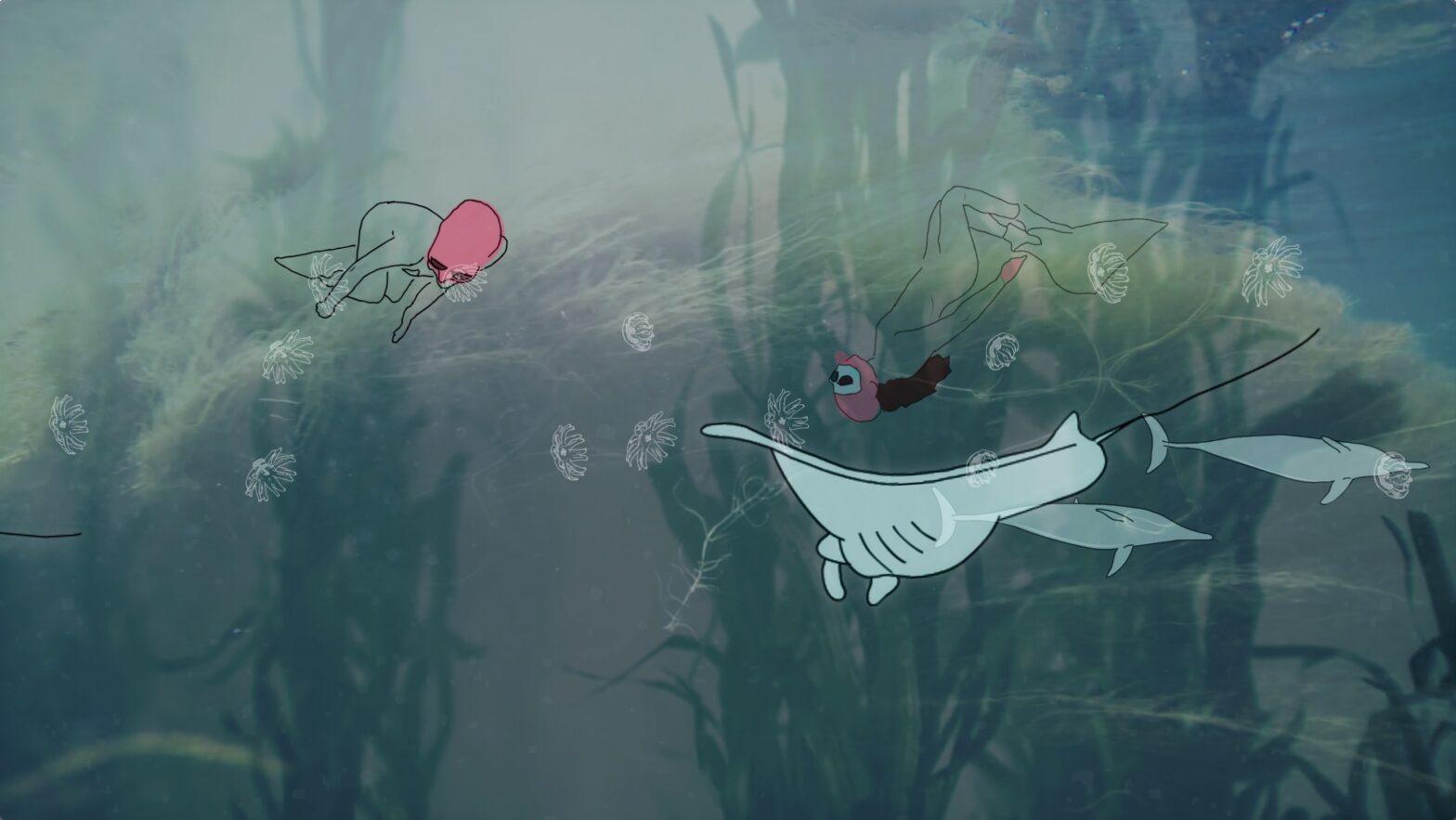

Sound and visuals are strongly connected. My interest in experimental noise is that it does not have a structure, which goes well with abstract videos. I have been playing music since I was 12 years old, and at the same time I studied painting. Doing both at the same time from a very young age, when I discovered video art there was no question that I wanted to do that.

I’ve used a lot of analog setups in the past. But I use less of it now. I still like a pure analog setup, but I’m just in a different phase. I like to keep it simple with fewer gears in my studio at the moment. I incorporate the ideas that I have learned from working on analog videos into the digital video-making process. One of the things that are fascinating about what I can do with analog video is video feedback. I try to simulate that in the digital setting. The exact process might be different. But the concept is the same either in analog or digital.

“I imagine that the future of computing will be more organic and fluid.”

I still have a video analog setup in my studio. For me it started to get kind of boring, and to break out of it one of the solutions was to buy more gears. I feel that the parameter is very limited because if you buy gear, then your creative process becomes shaped by the vision of the person who made that gear. I don’t like that, so I use my own video feedback technique with After Effects, which not many people do, and therefore it feels like it is my own tool and my own technique.

I also randomize a lot of elements in my audio production, working with a set of parameters. I set a tone, add notes from here to here, and allow a bit of randomness. But that’s as far as I go. I don’t use a coding environment such as PureDate to make audio compositions, but I use audio production software and randomize it, which is similar in a way.

“I like the idea of creating Op Art, because it makes you question what you are seeing”

When experiencing your works, one cannot help but think of the beginning of the creation of everything with the representation of fluids and water.

Ha, I’m not sure. When people think of computers and technologies, they don’t really think of liquids and water. Machines are always dry and hard things. But I imagine that the future of computing will be more organic and fluid. People are using liquid elements in computing and I am fascinated by it. My videos feel very organic, particularly because they have an analog component, so it is not only about zeros and ones. I want to make everything organic as much as possible. It’s not easy, but I take it as my challenge to make things look more organic.

You have recently also been active in the NFT space, could you please share your experience with us on these projects and how you imagine NFTs becoming part of the more traditional art industry as a whole?

It’s been such a crazy ride with NFTs! I’ve sold plenty of work as I’ve never had before. And I’ve made a lot of new friends, and I discovered a lot of great artists I’ve heard of before. Overall it’s been a good experience for me. But I’m not a big fanatic of it either. I’m staying pretty low-key about it. Things come and go and I have no idea where this is going, honestly. I just focus on making good art, which has always been my thing.