Pau Waelder

The Berlin Biennale is celebrating its 12th edition with a program of exhibitions and events that take place in six venues around the city, until September 18th. The four main exhibitions are hosted by the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, the Hamburger Bahnhof, and the spaces of the Akademie der Künste at Hanseatenweg and Pariser Platz with a total of nearly 90 artworks by more than a hundred artists. Titled Still Present!, this year’s Biennale is curated by artist Kader Attia, with the support of an artistic team composed by Ana Teixeira Pinto, Đỗ Tường Linh, Marie Helene Pereira, Noam Segal, and Rasha Salti.

The main theme addressed by the current edition of the Biennale is the effect of colonization, in land and history as well as in bodies, people’s lives, identities, and mindsets. This subject touches cultural institutions too, by pointing out the presence of looted artifacts and forms of presenting colonized cultures that only contribute to open the wounds of a history of colonial abuse. In a text written for the catalogue, Kader Attia denounces the hatred of others (whether foreigners, people from nomadic cultures, those experiencing marginalization and anyone not submitting to heteronormative patriarchy) and the invisibility of the wounds that inequality and exploitation have caused:

“Invisibility is discourse’s preferred weapon of control: always in denial of the crime, the enunciator claims victory while disavowing all responsibility.”

Kader Attia, Still Present! Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (Kunst-Werke Berlin, 2022), p.24

The concepts of wound and reparation are key to Attia’s work, and he finds in the processes of decolonization and the way in which Western societies have sought to build an image of a perfectly homogeneous modernity, in itself blind to the wounds it has created, an ideal framework in which to suggest forms of reparation through art. Art, he claims, can resist political and religious obscurantism precisely because it is unpredictable and constantly aims to reclaim people’s attention. He also states that artists seek to capture the present at a time when algorithmic governance collects data from our past actions in order to predict our future behavior. Trapped in this calculation of probabilities, the present no longer belongs to us, stresses Attia, and for this reason it must be recovered by means of the experience of art:

“Standing before a work of art, the spectator is plunged into another temporality, radically different from that of their environment, inaccessible to the insatiable appetite of algorithmic governance. […] art deconstructs so that it may repair and evolve, generating new forms of interpreting the present.”

Kader Attia, Still Present!, p.34,40

Being present

The artworks exhibited at the Berlin Biennale show that artists increasingly use video, 3D animation and data visualization in their portrayal of the present. Reality is captured through live footage, digital images, and all sorts of visual documentation. The exhibition spaces are filled with screens and projectors, sometimes extending their presence in the room with objects and imposing installations. The rooms at the Akademie der Künste, the Hamburger Bahnhof, and the KW Institute are dimly lit and labyrinthine, with displays creating areas of attention, that lend each artwork a space of its own, secluded in itself and rarely enabling a dialogue with nearby pieces. The documentary nature of most artworks also forces viewers to read the descriptions on the wall labels and concentrate on the story that each artist is telling. In this sense, as Kader Attia suggests, the artworks succeed in plunging viewers into a different temporality and making them fully present.

Artists increasingly use video, 3D animation and data visualization in their portrayal of the present

This temporality is both created and controlled by the artwork: as philosopher Boris Groys points out, video and time-based arts determine the time of contemplation. Through moving image and sound, notably the voice of a narrator, the artworks capture the viewer’s attention and force her to remain attentive while the story unfolds. This creates a particular pace for the visitor that demands more time and less distractions: these are not instagrammable exhibitions, in which to portray oneself in front of a tremendously huge object or a fiercely immersive installation, but rather spaces of discussion filled with the voices of the unheard. The enormous amount of footage to watch, the complexity of the narratives and the information one is required to process may seem overwhelming to a regular visitor. However, it is worth taking the time to patiently examine the artists’ exhibits, both in the sense of their public presentation and in the sense of producing evidence in a fictional court.

Visual records, both images and videos, have been considered irrefutable evidence of a fact until digital technologies and fake news finally put every image into question. Obviously, the depiction of historical events has always been subject to the interpretation of the victors, with visual artists being complicit in the creation of a narrative dictated by those in power. Today, artists addressing social, environmental and political issues are well aware of how images and messages are constantly manipulated, and therefore tend to avoid a position of authority, providing instead bare data, appropriated or filmed footage, witness recollections, and the stories told by those who ask to be heard. In this manner, the artist acquires an aura of neutrality, an actor who exposes facts with fair intentions in the form of a cultural product that, as the space that hosts it, is far removed from the complexities of real life. While this may seem to neutralize the political involvement of the artists and the educational (or indoctrinating) power of the artworks, it is actually the contrary. Art exhibitions enable a space where politics and society can be observed with detachment, as though one was reading a fictional story, and this allows one to confront other voices, other mindsets and realities that would otherwise be quickly ignored or dismissed. Being present thus also means being receptive, and willing to, at least, accept the existence of realities other than those we have created for ourselves.

Fragments of a reality

Fragmentation is a salient feature in many artworks, which rely on a variety of elements such as photos, maps, written documents and found objects. In 24°3′55″N 5°3′23″E (2012/2017/2022), Ammar Bouras addresses the consequences of the so-called Béryl incident, an explosion that occurred on May 1, 1962 while the French carried out underground nuclear tests near In Ekker in the Algerian desert. He creates a photographic montage and a video piece that explore both the geological layers of the area and the long-term consequences for the land through the testimonies of its inhabitants. The multiplicity of perspectives described both by the photographs and the video footage question the official history, which buried this event, and the possibility of an objective truth.

Using CCTV footage of an Israeli military surveillance camera, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme tell in OH SHINING STAR TESTIFY (2019/22) the story of 14-year-old Yusef Al-Shawamreh, who on March 19, 2014 crossed the Israeli separation wall to pick akkoub (an edible plant important in Palestinian cuisine) and was shot dead by Israeli forces. This footage, which circulated online and was later removed, is projected onto a series of wooden panels that capture, distort and hide the projected image in their shadows, as other filmed and appropriated sequences enrich the context of the grainy scene and its crude depiction of the facts. Fragmentation in this case conveys the multiple layers of this event, framing it in a wider social and political context while avoiding the obscene spectacle of death that media outlets have made of drone footage since the Gulf War.

Poison Soluble. Scènes de l’occupation américaine à Bagdad (2013) by Jean-Jacques Lebel, dives into this morbid spectacle by collecting and enlarging the snapshots taken by US military personnel while torturing and humiliating prisoners at the infamous Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. With these magnified pictures, the artist builds a labyrinthine installation in which the visitor gets lost, surrounded by horrifyingly graphic depictions of violence and sadism, and the no less upsetting portraits of the proud torturers, smiling at the camera. The artist sought to force an involvement of the viewers, but the harshness of these massively distributed images also calls into question whether Lebel has not created yet another spectacle, this time for an art audience. Such criticism was raised by Iraqi curator Rijin Sahakian shortly after the opening of the Biennale and has finally led artists Layth Kareem, Raed Mutar, and Sajad Abbas to withdraw their work from the exhibition in protest.

CCTV and drone footage have been used by the media in sensationalist reporting, to a point where their value as evidence is replaced by their effect on the audience

This controversy illustrates the power of the photographic image as both evidence and raw material subject to manipulation. This is particularly true for digital photography. The low resolution snapshots from Abu Ghraib, with their pixelated, badly compressed textures, can be immediately identified as a private record of an event, not meant to be seen outside a closed circle. CCTV and drone footage also belong to this category of images that have been continuously used by the media in sensationalist reporting, to a point where their value as evidence is replaced by their effect on the audience.

Data speaks for itself

In contrast to the first-hand, visual testimony found in grainy digital footage from CCTV, drone, and smartphone cameras, data analysis and visualization provides a much more detached and abstract, but equally telling, presentation of evidence. Photographs and video clips remain important, but generally as a complement of graphs, simulations, and diagrams mapping the collected data in a meaningful way.

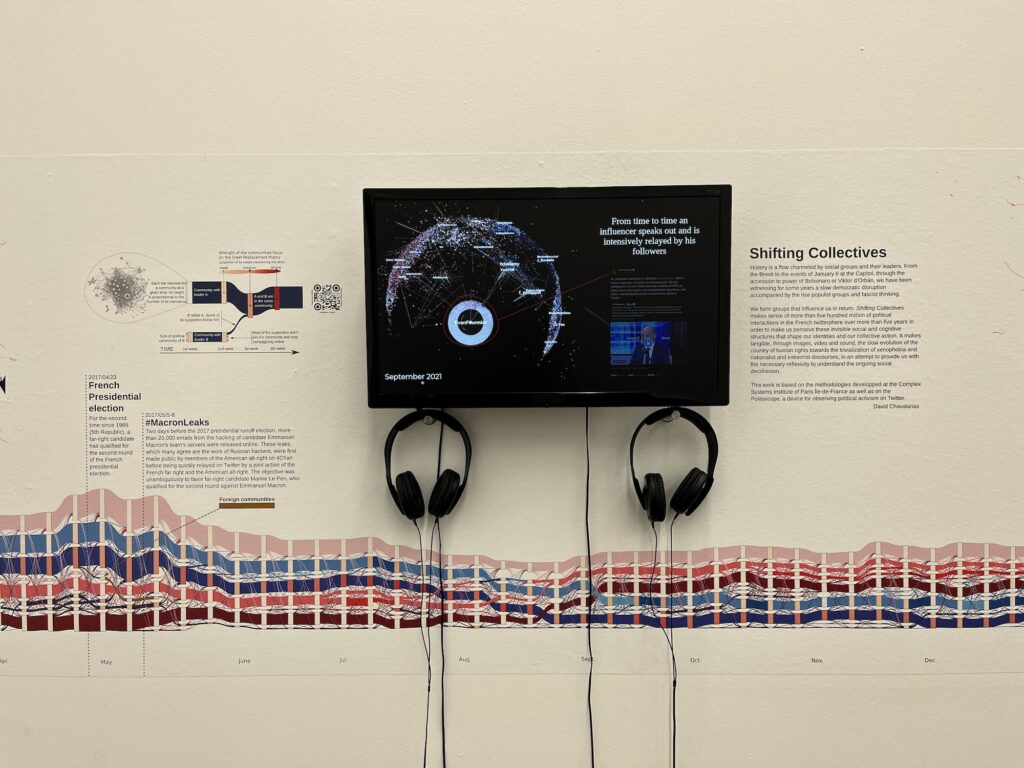

David Chavalarias’ Shifting Collectives (2022) exemplifies this turn towards data visualization in a detailed observation of the French political landscape. A researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Paris, Chavalarias explores the degradation of democratic values and the trivialization of xenophobia and ethnic nationalism through a timeline extending the long of a wall accompanied by a series of graphs, images, video and sound. The display of information aims to disentangle the complex interplay between political candidates, ideologists, social and workers groups, and the media, in order to provide quantifiable evidence of the rise of populism and right-wing extremism. Again there is here a collage of fragmented documentation, although it is presented under a unifying graph and the authoritative voice of science: the orderly display of facts, names, and numbers builds the narrative by itself.

The collective Forensic Architecture is well known for their detailed research of cases of state violence through the analysis of architectural spaces and materials, using simulation techniques and information collected from witnesses. In Cloud Studies (2021) they address a type of aggression that, unlike bullet holes and broken glass, leaves no visible trace but causes permanent damage: the toxic clouds created by tear gas, airborne chemicals and petrochemical emissions. Fused in a single video, the collected documentation including video footage, 3D animations, fluid dynamics simulations, and countless photographs analyzed using machine learning techniques, is presented in a linear narrative in the form of a lecture that nevertheless includes certain dramatization. As in Chavalarias’ work, the display of information speaks for itself although here it is more scripted and lends itself to aesthetic concerns that confer the video its own identity as an artwork.

In both artworks the presence of video and computer generated images denote the central role that this kind of imagery has adopted in the depiction of events by news outlets, at a time when the dominating perspective of a satellite or drone view and the tidy simplicity of a computer simulation can provide a much clearer and seemingly indisputable perspective than any number of witnesses’ accounts.

Eyewitnesses

The voices of those who were there, the victims, the passersby, also the perpetrators, the plotters and the followers, tell stories that contain their own truths and commonly share the authenticity of a firsthand account. Every person describes their experiences with a mixture of truth and fiction, as a result of their interpretation of reality mediated by their beliefs. Thus, in every witness account there is a margin of doubt, an uncertainty that artists can explore in the depiction of their stories.

Omer Fast’s A Place Which Is Ripe (2020) presents the testimonies of two former London police officers who explain the ubiquitous presence of surveillance cameras in Great Britain in connection with the murders of two-year-old James Bulger in 1993 and fourteen-year-old Alice Gross in 2014, two notorious crimes that were solved thanks to CCTV footage. The footage showing Bulger taking the hand of one of his murderers was in turn widely distributed by the media and contributed to popularize the notion of the surveillance camera as a reliable witness. Fast films the officers from behind, to protect their identities, and combines their interviews with Google image searches based on their words, all displayed in three smartphones placed inside a drawer. The Google searches illustrate the officer’s accounts with a detachment that echoes the monotone sound of their voices and produces an eerie effect of repetition and normalization. The automated selection of the images also points to the development of surveillance cameras managed no longer by people, but by artificial intelligence programs. The terrible images that have transitioned from unquestionable evidence to morbid spectacle now become simple indexers of events for a computer to identify them.

In every witness account there is a margin of doubt, an uncertainty that artists can explore in the depiction of their stories.

A different form of indexing can be found in Elske Rosenfeld’s AN ARCHIVE OF GESTURES (2012–22), an exploration of the revolutions and revolts of 1989/90 surrounding the fall of the Berlin Wall and the re-unification of Germany. Through the notion of “gestures,” she proposes a blueprint for understanding how these uprisings lead to collective action and how the events are recorded and told. Again, the witness is a camera. The gesture of “interrupting” is analyzed by editing a video recording of the first session of the Central Round Table of the GDR, in which members of the new political groups and citizens movements and of the established parties came together to discuss the role of the Round Table in aiding the democratic transformation of the country. Rosenfeld focuses on a moment in which the meeting was interrupted by the voices of protesters out in the street. Going back and forth through the footage, she divides the scene in two, repeats certain gestures of the participants, captures their reactions and hesitation upon being told what is happening outside. As with Fast’s film, editing is a key element in building the narrative. Both artists, as interpreters of the witnesses’ accounts, make the story their own.

Beyond fiction

Our perception of the present is clearly mediated by the eye of a camera, but not only a photographic or surveillance camera. The virtual camera of a simulated environment in a video game or a 3D animation also creates a reality of its own, that can be experienced as intensely as our physical surroundings. Video game worlds, with their endless possibilities, can also hold a hyperbolical mirror to our reality, making visible those aspects that are hidden or ignored.

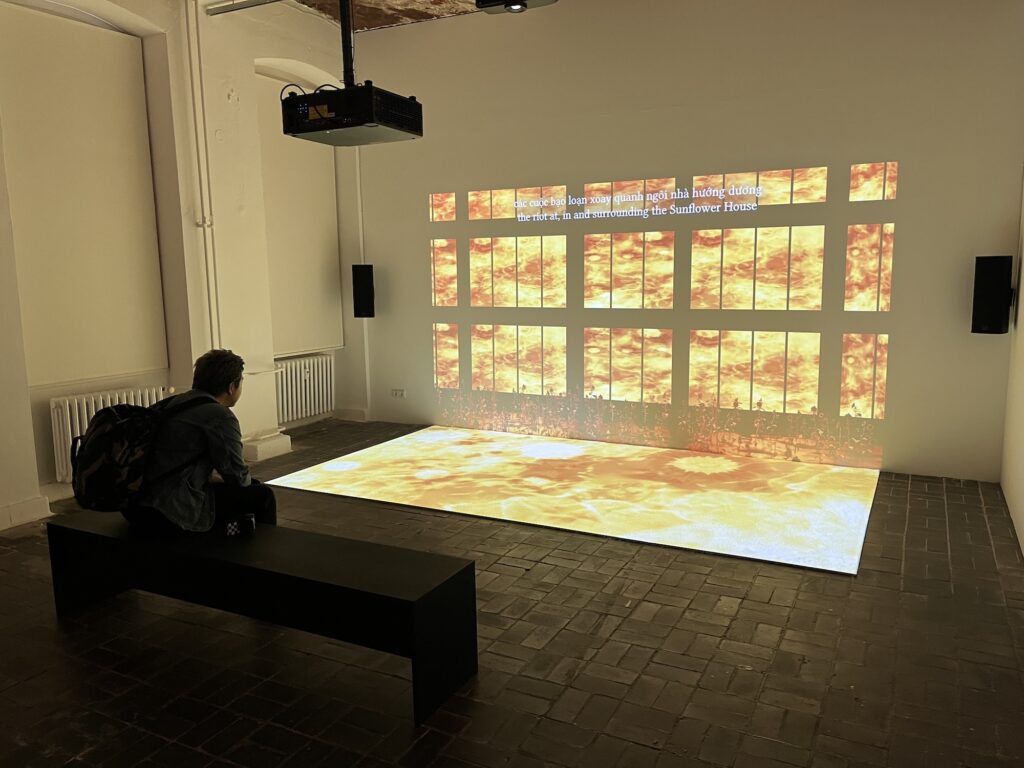

Maithu Bùi’s Mathuật – MMRBX (2022) is a video installation based on a virtual reality game that addresses the Vietnamese diaspora through mythology and magic rituals for communicating with the dead. The virtual space here allows for a suspension of disbelief and the assimilation of a set of cultural codes that belong to the artist’s personal memory and the country’s collective history. The video installation occupies the room in a way that invites to perceive the projected images as a real space and immerse oneself in the narrative that the artist has created.

Zach Blas goes one step further in this direction by creating a theatrical setup in PROFUNDIOR (LACHRYPHAGIC TRANSMUTATION DEUS-MOTUS-DATA NETWORK) (2022). An ambitious installation composed of eight screens and two projections, the piece presents a fictional AI god that feeds on the emotional tears of simulated humans. The tears are transformed into text, images, and sound, in what is seemingly an autopoietic system that seeks to compute human emotion. Continuing his exploration of the politics and imaginaries surrounding facial recognition and predictive policing based on artificial intelligence algorithms, Blas creates a dystopian world in which humans have been replaced by their avatars and emotions have become data. While this overtly fictional story seems to be far removed from the reality depicted by Bouras, Abbas and Abou-Rahme, or Lebel, it is nevertheless deeply rooted in our present. Blas’ subject matter requires a different form of expression, which is more effective as an extravagant fiction than it would be as a collection of documents and people’s accounts.

Media art has often been described as the “art of the future,” but as these works show, it is an art of the radical present.

This selective vision of the artworks on display at the Berlin Biennale aims to point out how artists address the present through moving images, appropriated footage that was leaked online, witnesses’ accounts recorded on smartphones, simulated environments and 3D-rendered fictions. These contents, and the way they are presented, allow in turn to create a different temporality, as stressed by Kader Attia, that leads the viewer to a state of presence. If, as the artist and curator suggests, we must be “still present,” this can only be achieved through art that does not claim to be atemporal, but that is time-based. Media art has often been described as the “art of the future,” but as these works show, it is an art of the radical present.