Pau Waelder

Julian Brangold (Buenos Aires, 1986) is one of the leading names in the growing digital art community in Argentina. Through painting, computer programming, 3D modeling, video installations, collage, and a myriad of digital mediums, he addresses how technologies such as artificial intelligence and data processing are shaping our culture and memory, as well as our notion of self. An active participant in the cryptoart scene and NFT market in Argentina he has been exploring art on the blockchain since 2020 and is currently the Director of Programming at Museum of Crypto Art, a web3 native cultural institution.

Coinciding with the launch of his solo artcast Observation Machines, which brings together a selection of four artworks from a recent series exploring classical sculpture and computer glitches, we sat down to discuss his work and views on the digital art scene.

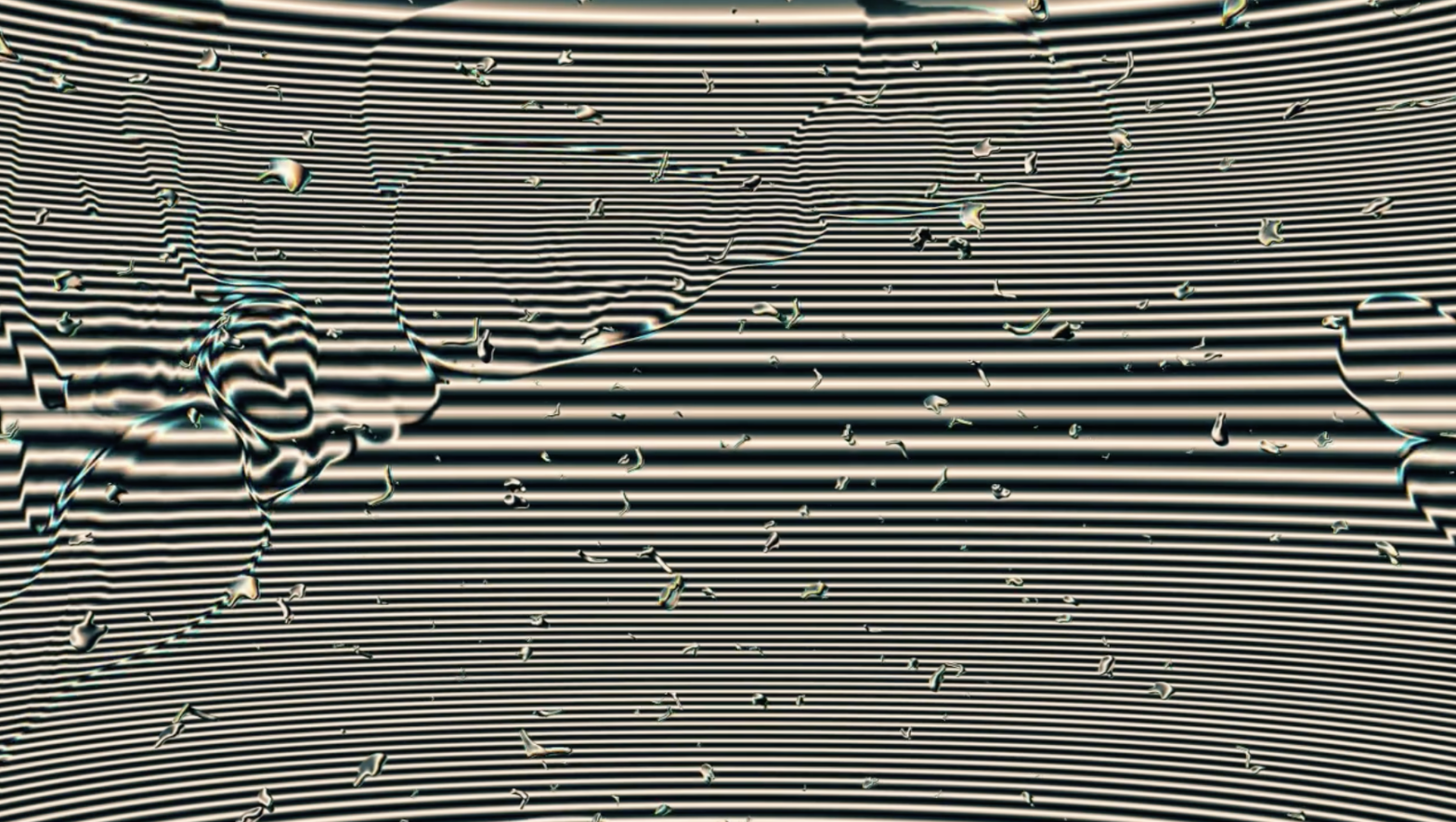

Julian Brangold, Observation Machine (Bifurcation), 2022

Every artist studying Fine Arts is confronted with classical sculpture as a model and a source of inspiration, to the point that this particular period in the history of sculpture has become intrinsically associated with the concept of Fine Arts and academia. Is it correct to see in your work a reaction to this?

I see the aesthetic territory of Greco-roman classical statues as a marker for how contemporary imaginaries are constructed today. Our cultural identities are shaped by this legacy, and my interest resides in a sort of ontological anchor to this node, and how it connects with the now, how it has an impact on our collective cultural memory. More specifically, I am fascinated by how information storage technologies today shape our relationship to that legacy that exists in the form of data, and how it makes us connect to that information so differently from how we could in the past.

“My approach is mediated by error aesthetics, the computing error as a sort of visualizer of the hidden side of technology, of a great revealer of what commercial technology tries to hide.”

My bond to this imagery began when I came across an overwhelmingly enormous Russian database that stored hundreds of thousands of photographs of ancient Greco-roman culture (art, architecture, ornaments, technical objects). I wanted to explore how appropriating this complete sea of information as a subject matter would look like. The first exploration came from creating a data scraper that stole all the images of sculptures from the website and then grabbing small bits from that huge span of data and developing an intimate relationship with just one cutout to create something very human, very handcrafted and detailed. In this case a drawing, or a series of drawings. In the process, I also explored how technological tools would facilitate a sort of mishmash of the aesthetic “trigger” of these classical imaginaries (we know immediately what we are seeing when we come across these images) with modern computer aesthetics.

Physical mixed media artworks such as the Anonymous Elements of Cultural Memory (2019) series already show an interest in classical sculpture, a form or rendering (as a drawing) and duplication. These elements are clearly present in your digital artworks, what does working with 3D rendering bring to your original intentions in these series?

This is a very interesting question because for years I worked with flat images, as you mention, in drawings, and then translated them to physical large-scale collages where the process of printing and then hand-pasting the different parts of the composition was part of the work itself. The jump to 3D was in the same line, a large database of 3D scanned classical sculptures (in this case one that is meant for people to be able to print out their own versions of this classic statuary), but I became very enticed with the idea of manipulating these object in 3D space because the visual possibilities expanded enormously. My approach is mediated a lot by error aesthetics, the computing error as a sort of visualizer of the hidden side of technology, of a great revealer of what commercial technology tries to hide. So error was a big part of the transition from 2D to 3D, in the sense that the manipulations were about destroying these 3D models, breaking them, bending them, and then seeing what happens when I tried to put them back together. 3D models have a lot more potential for destruction, at least in my mind, because there is simply more data to work with, more possible iterations of the same object when, for example, you can rotate 360 degrees.

Your digital drawings bring to a tangible medium (paper) a single fixed composition that stems from your exploration of 3D models. How is the process that goes from the 3D model to the drawing? Do you build the composition “manually” (intervening in every step) or do you let the software decide on certain aspects of it?

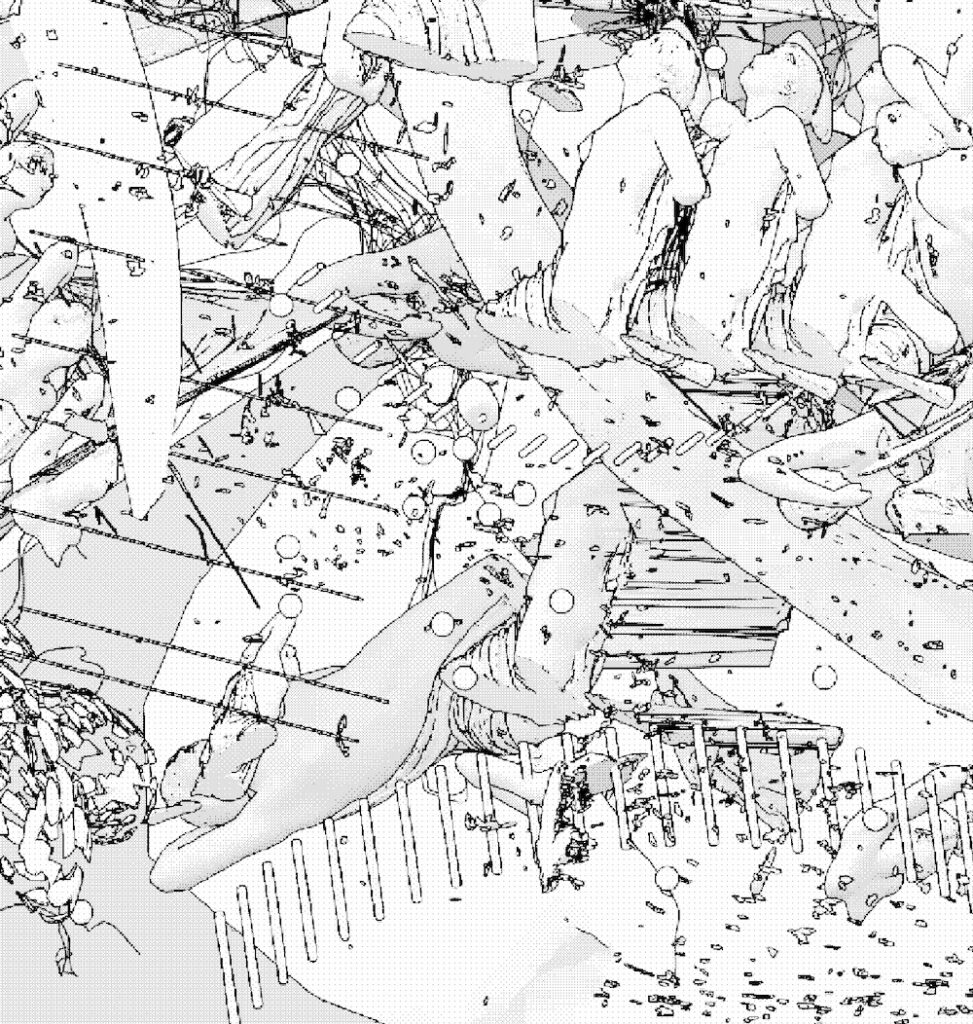

I love to use randomness in my work. I am very fond of serendipitous findings in the process of building an image, especially when working with computers, because this error aesthetic shines through. I use a lot of procedural tools in 3D to create the destruction and decomposition of these 3D models, and the outcomes are usually very surprising and accidental. The first explorations based on photographs from 2019 and 2020 were digital but hand drawn, because I was looking to convey a more intimate relationship with the material. Even the return to the physical outcomes (the printing and then collaging these drawings on a canvas) was also related to that same intention. The later 2021 and most recent drawings are created with 3D shading tools that imitate a flat style, a technique called “Toon Shading”, mixed with a tool in Blender called “Freestyle”. I find it funny to go back to 2D using 3D tools, it’s like the flat, drawing aesthetic is somehow calling me.

In your video works there is often an atmosphere of decay and decomposition, the latter being also present in Observation Machine, albeit as something fluid and reversible. Is this a comment on our society, or rather on the ephemeral nature of 3D renderings, despite appearing “real” and “solid” to the eye?

It is definitely more related to the ephemerality of 3D objects. It has to do with this notion of “showing what is behind”’ the tools we are using, of using technology to reveal more than what we try to hide. I use industrial and commercial tools that always invite us to orbit closer to streamlined aesthetics that tend to deny the fact that they are being used, to “cheat” the eye into realism, or hide the process happening behind. This is a constant in all artistic disciplines. Film montage for example works very hard to hide itself, to give a feeling that you are “not watching a film”. I think (and this is not a very new notion) that there is a form of subversion in using the tool in ways it is not intended to be used, and thus the outcome is not about cheating the eye, but more about revealing what hides underneath. This is where error, destruction, decay, and “untidiness” come to play.

Julian Brangold, Observation Machine (Bifurcation), 2022

In the Observation Machine series, we see several classical sculptures that are used as raw material for digital manipulation. Which sculptures did you use for these artworks? Are these 3D scans that you made yourself, or that you took from an online library? If so, which one? Is the iconography or original placement of the sculptures relevant to you, or have you chosen them mainly for their aesthetic appeal?

The 3D scans come from an open-source library called “Scan The World”, as I mentioned before, meant for people to be able to print out their own versions of classical sculptures. The process of selecting which sculptures I use for each work varies from series to series. In this case, I wanted to explore different possibilities of the 3D tool I’m using (Blender), and ended up choosing the sculptures using very visual parameters (scale, shape, amount of information). Sometimes I like to empty the sculptures of their cultural meaning and just look at them as pure subject matter, almost like an abstract object, particularly to see what happens if I do that, what happens to the archival baggage. It is kind of paradoxical, but I like that it’s all intertwined in the same process.

A common trait of the artworks included in this artcast is that, unlike previous works, they play shadows and contrast to appear flat, going back and forth between what could be seen as a digital painting and a 3D object floating in a virtual space. Color also plays an important role in creating this perceptual effect. Can you elaborate on these aspects of the artworks?

“Observation Machines” is a series of time-based works that present an emulation of a machine learning process being operated on these sculptures. The movement and sound are inspired by a machine’s logic of movement. It is an imagination exercise: what would it look like if a machine were trying to study this object? In the works included in this artcast (a subset of this series), I wanted to explore how when using color alone within the 3D software the image would transition from two-dimensional to three-dimensional. The only thing changing in these pieces besides the sculpture is the color of the background, which makes the shadows and the textures react differently and thus reveals the depth of the object being observed.

Julian Brangold, Observation Machine (Iteration), 2022

You have come to prominence in Argentina as a leading figure in the contemporary art scene linked to NFTs. Can you tell us how this scene is evolving and how do you participate in it? What have NFTs brought to digital artists in Argentina, and is it different from other art scenes, as far as you can tell?

I have a background in the traditional art world, where I spent almost 12 years, so for me entering the crypto art world had a very strong influence on how I see my practice and my career. Argentina hosts one of the largest, more organized communities of crypto artists in the world, called Cryptoarg. I was part of the conception of this community from the start, and the relationship with other artists that came from very diverse backgrounds in art and the creative industries, intertwined with a novel art world that had very new dynamics and potentials, was a very impactful experience for me. Argentina already has a very close relationship with crypto technologies, being one of the “capitals” for Ethereum development, for example. I think we are very prone to adopting alternative means for the distribution of labor, information, and capital management, mostly because of our very precarious economic conditions.

“The crypto art scene is very different from the traditional art scene. The tools for the experimentation, collaboration, and distribution of art make it a very fertile landscape for exploration and experimentation.”

The crypto art scene is very different from the traditional art scene. The tools for the experimentation, collaboration, and distribution of art make it a very fertile landscape for exploration and experimentation. Honestly, I find the traditional art world quite stagnant in its approach to technology. It is almost as if traditional art curriculums turn their back to our contemporary technological realities, and if they adopt some sort of look or introspection that relates to technology, it is usually quite a few years late. It is crazy to think it is still hard in some traditional circles to have technological art considered a valid art form. This is why, for me, the crypto art environment is interesting, it is very technology-native, and so the attention to what is happening with technology is very novel and updated, it is fast-paced in the same manner that technological development is, and it provides an honest, accurate look at contemporary culture, in a way that the traditional art world can’t keep up with because of its interests and scale. I don’t renounce the traditional art world, I’m very much interested in a lot of things that it has that the crypto art scene doesn’t, so I keep advocating for a cohesive intertwinement of both, a mutual nurturing. Even the distinction between both feels a bit silly sometimes. It’s all art we are talking about in the end. But the crypto art world developed so fast and came out of the underground so quickly that I feel it missed a bit of depth in its contextualization and organization.

Julian Brangold, Observation Machine (Fragmentation), 2022

You are now director of programming at the Museum of Crypto Art. Tell us about this entity and your role in it. How do you define crypto art, and what do you find more interesting about it?

The Museum of Crypto Art (MOCA) is in my mind the very first web3 native proper art institution project. It began as one of the largest crypto art collections and became a space for empowering, contextualizing, and displaying digital art in experimental new ways that were in tune with web3 technologies. Decentralization plays a very important role in the museum’s ethos, and so my role as director of programming is to create a cultural output curriculum that follows that ideology. This is why, beginning next year, we will begin to experiment with the museum’s DAO and have the community of art enthusiasts, collectors, and artists participate in the construction of that curriculum collectively.

We are looking into ways of creating an art program that escapes the top-down dynamics of traditional institutions, which are inescapably mediated by political and cultural bias, without losing the paramount power of cultural resources such as expert curation, historicization, critique, archiving, and the creation of artistic experiences. It is a very challenging project and holds a great deal of responsibility, but it is one of the most exciting ones I’ve ever been involved with.

“The fact that an artwork can be sold as unique to one individual at the same time that it is readily available for anyone to experience in its native form is very powerful.”

I find the definition of crypto art as challenging as the definition of art itself. I am a big advocate of definition by context, both in the notions of art and crypto art. So, I guess I would define crypto art as whatever art exists in the context of blockchain technologies. The same goes for art in general, which for me is whatever exists within an “art-appointed” context. As an artist, I find crypto art interesting in its nativeness to technology, and in its potential for experimentation and the exploration of distribution and commercialization. The fact that an artwork can be sold as unique to one individual at the same time that it is readily available for anyone to experience in its native form is very powerful.

As an Argentinian, I’ve struggled a lot with the accessibility of art (my artistic idols had exclusive exhibitions in London and New York all the time, so I simply didn’t have, and still don’t have, access to their works), so the fact that crypto art is an ecosystem that hosts art that is naturally networked and accessible to anyone with access to the internet is very captivating to me. The problematizing of certain arbitrary boundaries established by the traditional art market, between “the high arts” and other creative disciplines, is also something I find quite appealing. In general, I have to say that the disruptive nature of crypto art, and the fact that it challenges an art world status quo, is one of the most interesting things for me. It kind of fucks things up a bit, and I find that quite exhilarating, and honestly, quite necessary too.