Pau Waelder

Tamiko Thiel is a pioneering visual artist exploring the interplay of place, space, the body and cultural identity in works encompassing an artificial intelligence (AI) supercomputer, objects, installations, digital prints in 2D and 3D, videos, interactive 3d virtual worlds (VR), augmented reality (AR) and artificial intelligence art. In this conversation, that took place on the occasion of the launch of her solo artcast Invisible Nature curated by DAM Projects, she discusses the evolution of technology over the last three decades, her early AR artworks and her commitment to create art that invites reflection.

Your work is characterized by the use of Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality technologies, with pioneering artistic projects. Which technical challenges have you met over the last decades in the creation of these projects?

My first exposure to real time computer graphics was at MIT when I was a graduate student in 1982. At that point, writing everything from scratch, you had to program for a semester in order to get a cube that would rotate in three dimensions. Coming from an artistic and design background, I felt that this is not really where I want to create art right now, I’ll have to wait. And then about 10 years later, in 1992, Silicon Graphics came out with OpenGL, an open standard that made it possible to do real time interactive computer graphics on PCs. Then in 1994, I started to work with a company called Worlds Incorporated, which was taking this new potential for doing interactive 3D computer graphics on PCs connected to the Internet. At that time I worked with Steven Spielberg on the Starbright World Project, the first 3d online Metaverse for ill children, a virtual world where they could momentarily escape the space of the hospital. This first Metaverse was running on high end PCs, with fast connections provided by various high tech companies, but it was still unaffordable for people at home. The project ran from 1994 to 1997, and at that time the technology was still unstable.

“It takes maybe 10 to 15 or 20 years to get there instead of the five years that all the evangelists predict.”

So you must jump from that to 10 years later, when Second Life came about and this time people had more powerful graphic cards and ADSL connections at home. Second Life was able to create a much more developed virtual world, which seemed like the next phase of the Internet and all the corporations wanted to move there. Then around 2007-2008, probably due to the financial crisis, but also the rise of Facebook, which allowed people to share photographs on a common platform, the excitement around Second Life fizzled. And then if we jump another 15 years more, we find ourselves with still bigger processing power and faster connections. Now it is much easier to create virtual worlds than it was 25 years ago, partly because it is easier to create 3D objects, or you can buy them online, and also because of the advancements in hardware and software.

So, as you can see, big steps come on later than you think. It takes maybe 10 to 15 or 20 years to get there instead of the five years that all the evangelists predict. People talked about virtual reality at that time in the 90s as being a failure, just as they talked about AI being a failure in the 80s and 90s. And what they don’t realize is that technological change takes longer than you’d want it to. So it’s wrong to call it a failure. It’s more like: “Okay, we have to keep on working on this.” And if you wait long enough, 20 years or so, then you’ll get it.

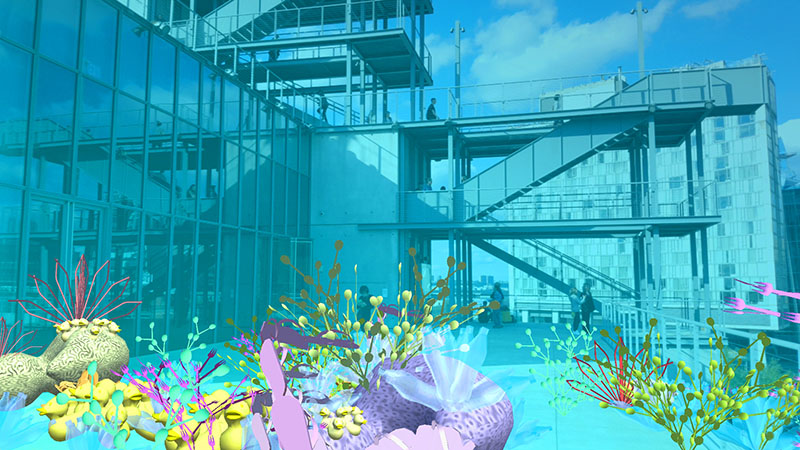

Video by Tamiko Thiel, Rewilding the Smithsonian, 2021. Created with the ReWildAR AR app (2021, with /p). Commissioned by curator Ashley Molese for the 175th anniversary of the Smithsonian Institution, in the Arts and Industries Building.

Interactive 3D and VR artworks such as Beyond Manzanar and Virtuelle Mauer have a strong narrative component as they explore historic and political issues. What is the role of the user in constructing these narratives?

Basically, what I tend to do is look for key moments that I think can be expressed and experienced and communicated better in virtual reality than in other media. In Beyond Manzanar, for me that was the moment where you’re sitting in a beautiful Paradise Garden, and you see the mountains covered in snow around you. This is an image from the book Farewell to Manzanar by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston: the author tells that when she was an eight-year-old and she was imprisoned in the camp, she would pick a viewpoint where she couldn’t see any guard towers, any barracks, nor barbed wire fence. And she tried not to move for the longest time, because as long as she didn’t move, she could preserve the illusion she was in paradise of her own free will. As soon as she moved, she saw that she was indeed in prison, she fell out of paradise back into prison. And so this moment occurs in Beyond Manzanar, where you enter a garden which is framed by the beautiful mountains. But if you go too deeply into the garden, then boom! – the garden disappears, and you’re back in the prison camp.

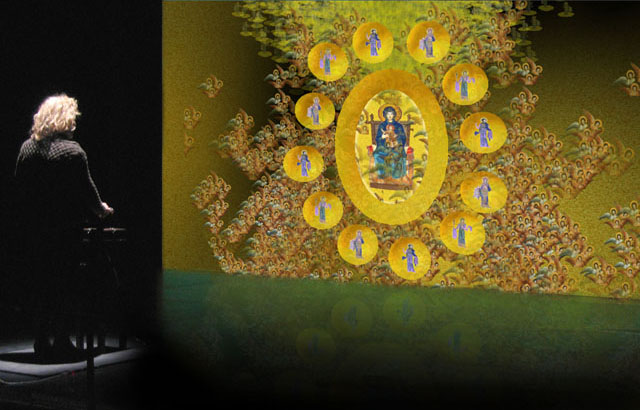

My second piece, The Travels of Mariko Horo, has a much more complicated structure with several heavens imagined by a time traveling 12th century Japanese female artist inventing the West in her imagination. In this work there is this moment when you enter the different churches, which are in fact liminal spaces between the prosaic everyday life and the world of the supernatural. When you cross that threshold, Mariko Horo takes you to heaven or takes you to hell. But it is always by your own free will, you’re always making the decision and making the motions that all of a sudden present you with the consequences of your decisions.

By Tamiko Thiel, with original music by Ping Jin.

Finally, in Virtuelle Mauer/ReConstructing the Wall, I introduced some characters that take you in a time travel through the history of the Berlin Wall. But if you cross over the invisible boundaries of the former Death Strip,, then you fall back into the 80s, the wall appears behind you. So in all three pieces, it’s really about letting you feel like you have the freedom to go anywhere you want and do anything you want to do. But then you must face the consequences of these actions, which might take you to Paradise or they might take you to prison. But you always feel like it was your decision to go there, or to examine this, and therefore you’re sort of complicit with whatever happens to you.

Video by Tamiko Thiel, Atmos Sphaerae, 2022. Created with the Atmos Sphaerae VR artwork, 2021.

Creating artworks in Augmented Reality offers the possibility of intervening in institutional art spaces uninvited, as you did at MoMA, the Venice Biennale, or TATE Modern, or within a curated exhibition, as is the case with Unexpected Growth, which was shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Can you tell us about the creative process in both cases and your experience with “guerrilla” interventions versus curated exhibitions using the same technology?

Let’s start with We AR in MoMA, an augmented reality project created by Sander Veenhof and Mark Skwarek that took place at the Museum of Modern Art in New York on October 9th, 2010. The iPhone had been around since 2007, as well as other smartphone models, and in the course of 2009 both Mark and Sander had been playing around with the technology and developing AR artworks on mobiles in public spaces. And then they realized they could also geolocate the artworks to have them appear in certain spaces, so they came up with this idea of doing the spectacular intervention at MoMA. I knew Mark from the art circles before we had both shown in the 2009 Boston CyberArts Festival, so he dropped me and many of his artist friends an email saying: “Hey, we’re able to do this now. Send me some content and I’ll put it up and we’ll do a flashmob at MoMA.” They were not asking permission from MoMA. They didn’t know about it, and they couldn’t stop us. At that time, people didn’t realize that location based AR could be used anywhere. But then it turned out that they did find out about it beforehand, because Mark and Sander were doing the intervention as part of a citywide public art festival of psychogeography, so it was publicly announced by the festival all on Twitter. MoMA actually posted a link to the festival and said: “Hey, looks like we’re going to be invaded by AR,” which was very forward thinking and embracing this new development in technology. So, that was incredibly good publicity. It was a really exciting moment, when we realized that there were these possibilities that the new technology was bringing about. I would say this was a path breaking exhibit in the history of media.

After this intervention at MoMA, the artists who took part in it created the group Manifest.AR. We were thinking about where to do the next incursion, and since I live in Munich, which is a six and a half hour beautiful train ride to Venice, I suggested we go to the Venice Biennale in 2011. It was a group of about eight of us. We created virtual pavilions that were located inside the Giardini and at Piazza San Marco, so that people who didn’t want to spend money to enter the Giardini could also experience the artworks in a public space, because the Giardini, with its walls around it is a classically closed curatorial space. The point was that having your work shown at the MoMA or the Biennale is a sign of achievement, of having been able to enter these closed curatorial spaces, but now with AR interventions that was not true anymore, anybody can place their artwork wherever they want. But then people’s reaction was: “Oh, wow, you’re showing in the Venice Bienniale, you’ve made it!” Then we told them we hadn’t been curated and that we were doing this of our own accord, but people would respond: “Oh, that’s even better.” So we thought we were doing this sort of Duchampian breakdown of all sorts of structures that define prominence in the art world. Duchamp exhibited his famous urinal not to say that an artwork becomes an artwork when an artist says it’s an artwork and places it in an art context, but to state that this whole thing is ridiculous.

“The point of putting our artworks at the MoMA or the Venice Biennale was that with Augmented Reality anybody can place their artwork wherever they want.”

These interventions gave us a feeling of exhilaration that we could hold our own exhibits anywhere, even though no one in the art world was interested in media art at that moment. And we could also play off site. Because AR is a site-specific medium, you’re always dealing with the site. And that opened up whole new possibilities. Interestingly, shortly after that, George Fifield, the Boston Cyberarts director, arranged our first invitational show at the ICA Boston. This was in April of 2011. The ICA curators didn’t understand how the technology works. They said: “Okay, you can do it on the first floor, but not on the second floor. You can do it in the lobby and outside, but you can’t do it inside of the galleries.” And we had to tell them it doesn’t work that way. The artworks are triggered by a GPS location which has a radius of a mile or so.

As for showing Unexpected Growth at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, it was thanks to Christiane Paul, the adjunct curator of media art at the museum. I have known her for quite a while, I think since about 2002, and she has curated me into many of her shows over the years in different venues, but this was the first time at the Whitney. She had of course done the visionary work of creating Artport, a space for net art supported by the museum, but she still hadn’t placed an AR artwork inside the museum. Then in 2014 she commissioned an AR intervention by Will Pappenheimer, Proxy, 5-WM2A, at the Whitney’s final closing gala for the old Breuer Building. So when she contacted me in 2018 to create an artwork to show at the Whitney, she had already gone through the process of introducing this technology in the museum. She invited me to create an artwork for the terrace, which is 20 by 10 meters in size. Since this was a big show, I needed to make sure that the piece would work properly, so I contacted the people at Layar, the AR app we had used in all our previous interventions, but by then they told me they would shut down their servers, so I had to find a solution. My husband Peter Graf, who is a software developer, told me he could write an app for me. We worked side by side on this project, so I realized he should co-author it with me and he came up with the artist name /p, so now the artwork is in the Whitney collection credited to myself and /p in collaboration. Now the artwork is not officially on view at the museum, but if you download our app and go to the terrace you can still experience it.

Video by Tamiko Thiel, Unexpected Growth (Whitney Museum Walk1), 2018. Created with the Unexpected Growth AR app (2018, with /p), commissioned by and in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

There is also the fact that the artworks are invisible, so how did you communicate their existence and solve the technical problems associated with having the proper device, software, and connectivity?

At the Venice Biennale intervention, Sander got in touch with Simona Lodi, director of the Share Festival Turin , and the artist group Les Liens Invisibles, who were together mounting another AR intervention The Invisible Pavilion. We created a common postcard with QR codes to download the app. We also invited people to come to Piazza San Marco and the Giardini on certain days and times and help them experience the artworks. Collaborating with the team from the Share Festival was a huge help, because those of us from outside of Italy had terrible connection issues, and also it was the first Venice Biennale when hordes of people were walking around with their cellphones, overloading the networks. The Vodafone network actually broke down in the Venice area. Gionatan Quintini of Les Liens Invisible loaned me his smartphone to show my work, and this is an example of the kind of collaborative atmosphere that you get in the media art world and that is not that easy to find in the contemporary art world. By connecting our networks with those of Share, we got a lot of publicity for both the interventions in MoMA and in the Venice Biennial, and that put AR in this early time into the media art history books, and therefore into the art canon.

Video by Tamiko Thiel, Sponge Space Trash Takeover (Walk1), 2020. Created with the VR space “Sponge Space Trash Takeover” courtesy of Cyan Planet and xR Hub Bavaria.

The artworks in your latest artcast titled Tamiko Thiel: Invisible Nature all deal with different aspects of our intervention of the natural environment. What has been your experience addressing this subject in terms of the balance between the artistic expression and the message you want to convey?

Perhaps because I started out as a product designer, with the Connection Machine being what I consider my first artwork, I am always thinking of my audience and how to communicate with them. When I approach political or social issues, such as climate related problems, I know that the really shocking photographs (for instance, a dead bird whose stomach is full of plastic) give you an immediate emotional jolt, and make you realize that this is a serious problem. But I personally cannot look at those images day after day, time and time again. So, balancing my work as an artist with my desire to communicate, sometimes I think that I should be a journalist, so I could write articles that can go into the details in much more depth. But how often do you reread the same article? So I think that what is truly the value of an artist making work about a subject such as these is that the art work can be exhibited time and time again, in different places around the world. And people might see it again, they may be willing to look at it time and time again, but not if it is something horrible and shocking. I’m traumatized enough by what’s happening in the world, so I’d rather create something that is not traumatizing for people, but at the same time it makes you think.

“What is truly the value of an artist making work about a subject such as these is that the art work can be exhibited time and time again, in different places around the world.”

For instance, Unexpected Growth shows a very colorful, bright coral reef on the terrace of the Whitney. And when you look at it more closely, you realize this beautiful coral reef is made out of virtual plastic garbage. So people are confronted with something that is really beautiful, but after a while they realize that they are surrounded by garbage. So my strategy is to seduce people with a strong visual composition that is captivating. And then, when I’ve got their attention, I let them figure out that there is actually something else going on here, if you actually spend the time to look at it.