Thomas Lisle

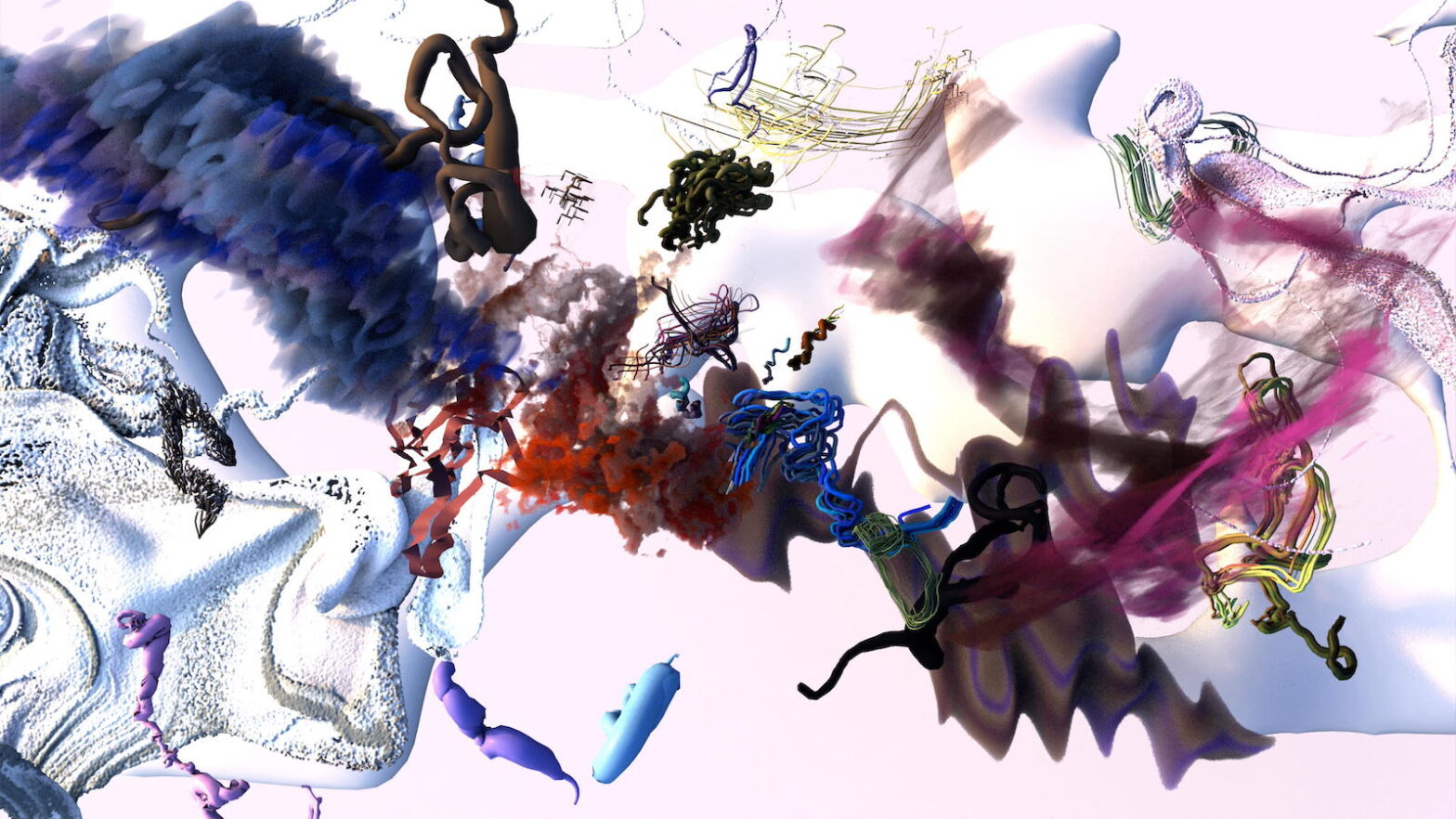

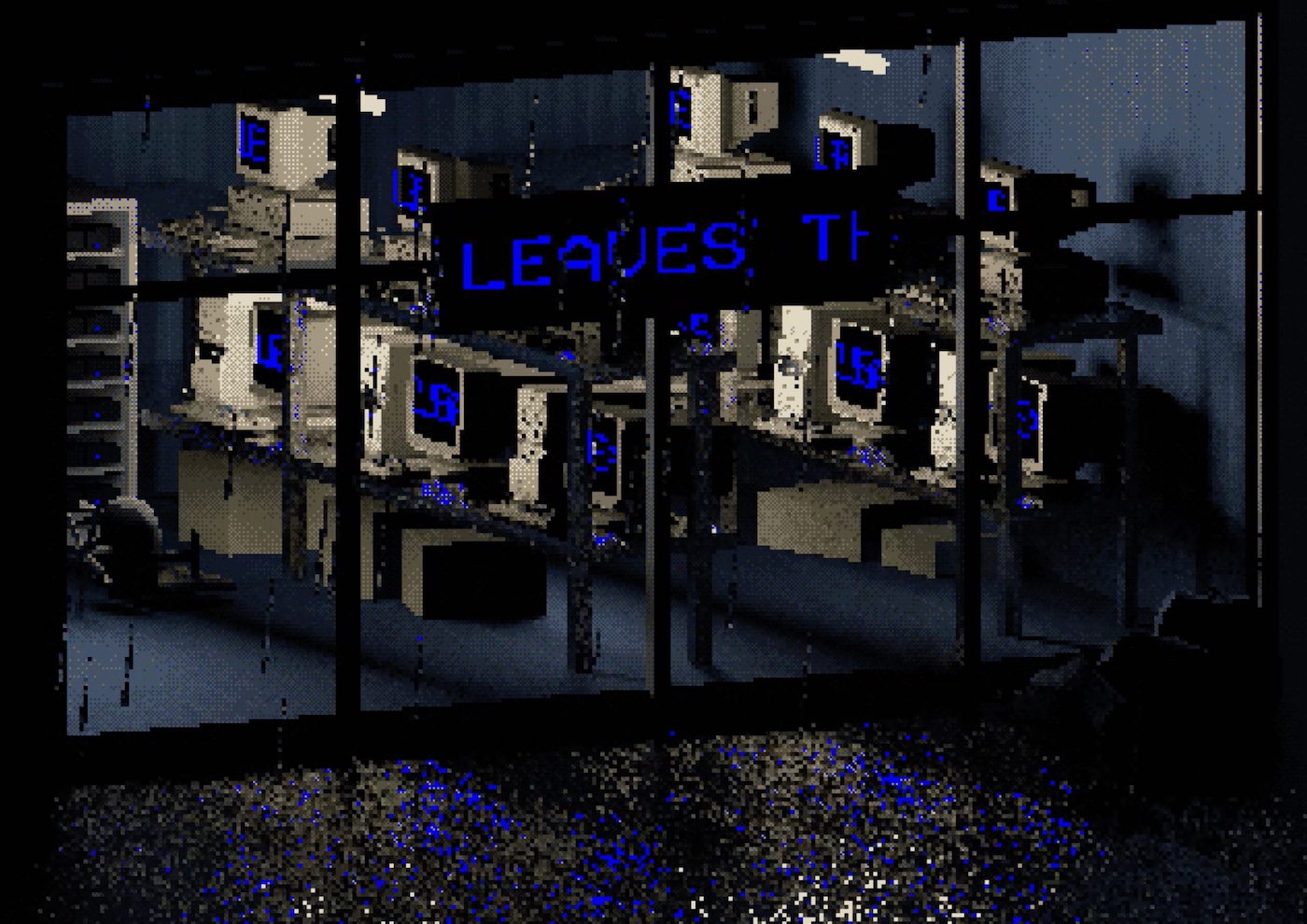

Thomas Lisle. Changing Values, 2023.

Our guest author, Thomas Lisle, is an artist with more than 30 years of experience in digital media who is exploring how painting transitions into a time based medium.

The art world seems to be in a moment of change; suddenly, digital is relevant to more people, and most of us have a computer and a smartphone. To many contemporary artists, digital technology is opening up new possibilities with new issues to circumnavigate. As an artist who has embraced electronic and digital art since 1981, I think it’s important to write a more in-depth analysis of the medium and its relationship to art and my art. My aim is to give those who do not have 40-odd years of experience a deeper insight into the technology, ideas, and practice of digital art from the perspective of my artistic output.

I started making glitch video art in 1981 as a process to make abstract painterly images, and I worked in this medium almost exclusively for 6 or 7 years. I’ve had lots of time to think about it. I eventually came to the conclusion that it’s really not enough; it’s like outsourcing the creative aspect, the making of the abstraction to some random process. Sometimes it makes great results, but there’s no control, that’s inherent in glitch art. I described glitch art then as a deconstruction. A glitch is a technical malfunction; it’s impersonal. Glitch seems to me a visual deconstruction that is a dead end in terms of artist development and impersonal. This makes glitch art ‘classical post-modernist,’ an art thinking and practice of the last century.

which formed the basis for a series of installations and videos.

A glitch is a one-off phenomenon that can look visually interesting; it’s not a way of making art that can be consciously built upon and developed; it’s an accident; it’s not consciously designed. Without control, it’s like throwing a bucket of paint over your shoulder –occasionally, something new and interesting might appear that you had never thought of. But the process of thinking about it and the journey of discovery, with tools you can control, is far more rewarding, stimulating, and produces results that can be built upon and explored. A metamodern approach, that comes from the artist, is needed. Generative and AI art, to me, are also classically post-modern, an art form initially developed in the 60s and 70s, impersonal in that it’s an algorithm rather than a human that makes the art.

Generative and AI art, to me, are impersonal in that it’s an algorithm rather than a human that makes the art.

As an artist, I’m interested in abstraction, visual languages, colour theory, hand-to-eye relationships, and composition, as well as psychology and human consciousness. Visual abstraction, both figurative and non-figurative, is the primary means of communication and expression. Figurative abstraction, above all, seems to me to be the most human mode of expression. Non-figurative abstraction, when the time-based medium allows abstract forms to take on a narrative, is not just a paint stroke/geometric shape; it is a paint stroke/geometric shape that’s saying something through its movement or time-based transformation. It represents so much more when consciously manipulated in time.

If you imagine Van Gogh, who famously painted a painting a day, making 1 minute of animation, which is 1,500 paintings (frames), it would take him about four years. I’m sure he would have gotten bored after a few days, as most people would. It’s this same time constraint of painting which drove my early glitch work. Then six years later, my artistic experimentation crossed paths with feature film effects software, which has developed and continues to develop sophisticated 3D systems to represent everything from humans to lava monsters.

If you were to ask me what digital medium offered artists the widest scope to produce any form, any liquid, any painting, anything in fact i.e ‘time based meta-plasticity,’ the art of the future. I would say without a moment of doubt it’s the software that has been developed to produce these box office hit movies. Software like Maya and Houdini. The main reasons that artists don’t use this software are that it’s difficult and time-consuming to learn and that it requires moderately expensive software and computers.

This workflow of making animation time efficient is called procedural. 3D software literally means that it makes everything in 3 dimensions; in films, you see it as a 2D output; in games, you see a 2D output that, if you are wearing goggles, it all comes out 2D but different to each eye making you think it has depth. In the digital world this means that everything you compute in 3D has a volume, it is basically sculptural in nature, rather than flat like a print, except, of course, paint in most cases has a thickness and layers. If the digital artwork you are looking at is flat, with no sense of depth, it is probably some kind of generative art; otherwise, it’s modelled or realised in 3D.

What appeals to me about painting/sculpture is and always has been the consciousness behind the artwork; it’s impossible for AI or an algorithm or a vast database of information to ever know what it is to be human. It’s the originality, poetry or beauty or chaos, craftsmanship, emotional, transcendent, humbling impact that humans bring to art that matters.

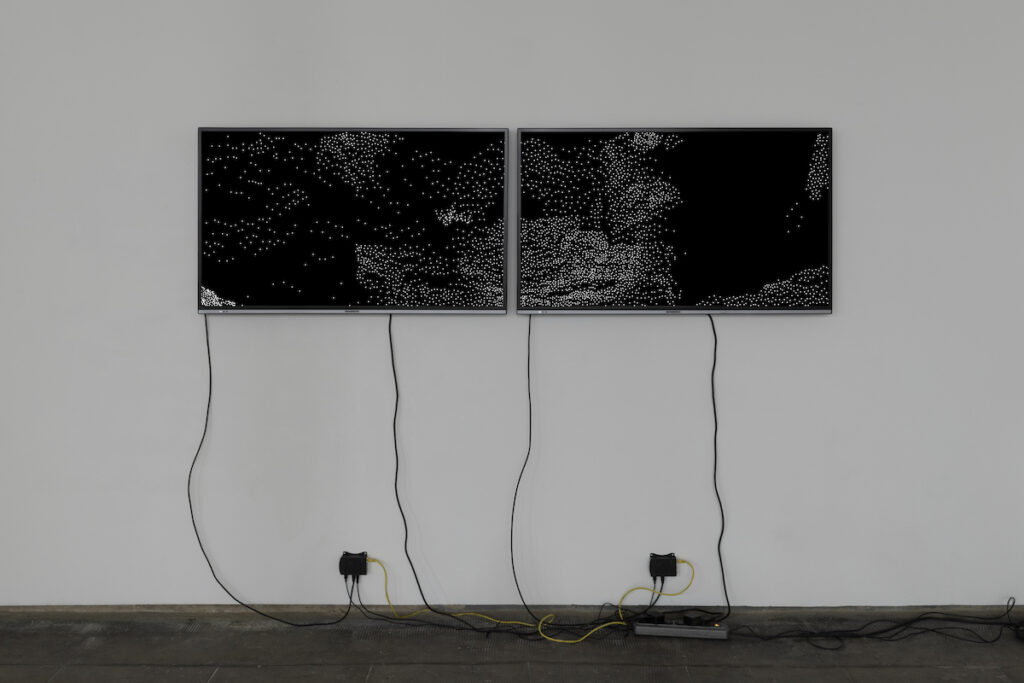

Thomas Lisle. Dynamic Relationships, 2023.

Human consciousness or AI

Art produced by AIs

Is it impossible for AI or an algorithm, or a vast database of information to ever know what it is to be human?

Joseph Weizenbaum first pointed this out in the 1960s when he invented the first chatbot, that AI can’t make judgements and have no values but that they can only calculate. His AI chatbot, Eliza, mimicked a psychotherapist and people believed it was a real person. It was clear to Weizenbaum that people thought the AI chatbot was a human or, in other words, had intelligence. The reason it’s relevant today is that psychological transference is taking place, and its ramifications of ‘transferring understanding and empathy’, basically human caring attributes to something that clearly does not care for the human individual, is basically very dangerous. Anyone who thought a computer cared about you would be totally deluded and could be easily manipulated.

Digital art made by AI systems is basically fooling us into thinking that what we are looking at is man-made and has human attributes. It’s the same transference that is going on with therapist chatbots like Eliza, it’s just harder to identify. The point is: do you want to hear, read or see something that talks about the human experience, the joy or otherwise of life, being in a relationship, the environment, or love, from a human or some AI program that scrapes the internet and draws conclusions based on things it can never understand? Even if somebody declares some software as sentient they will never be human.

Creating art with AI using prompts is a transference of responsibility, skills and judgement by the artist.

The AI we are talking about today in art is a tool that creates art or visual output based on prompts, this to me, is outsourcing the business of making the actual art to a third party. It’s a transference of responsibility, skills and judgement by the artist. For Weizenbaum, judgement involves choices that are guided by values. Computers can’t make human judgements; they can only make calculations, statistical inferences or glitches. Even more worrying is artists or anyone seeing themselves as interchangeable with a computer; that sounds sad!

Weizenbaum wrote in Computer Power and Human Reason that we should never “substitute a computer system for a human function that involves interpersonal respect, understanding and love.” It sounds to me like he’s talking about art.

Suppose I’m looking at the work of an artist who has been developing their art for their whole lifetime. This lifelong journey gives the artwork meaning and depth; it’s the result of this person’s desires, interests, experimentation, experiences, and influences; it’s their consciousness communicating to us about life, and the art they produce is in some ways a record of that and the manifestation of that consciousness.

Computers, if they become conscious, are going to think in terms of computers. Their reference will be how fast are my processors, how much storage have I got, where is my food source, and where can I find a mate? And so on. If they are conscious, you can’t force them to like humans, just as you can’t force a human to like computers. Consciousness means free will. It seems we are stuck in a world order where the most intelligent AI computer will dominate us all.

The real battle is not art. AI can’t replace artists, but more importantly it could have a profound effect on many other areas of our society and the planet. The dream that AI will give us endless energy, super batteries, cure cancer, and sort out all the world’s problems is as true as that AI may destroy us all!

Artist’s expression has been traditionally through the relationship of hand to eye in painting for most of its history – and that’s because there is a direct connection with our consciousness; draw anything while looking, and it will be personal/original to you. If people don’t know how things are made, they don’t understand the art. I think it’s essential to understand what’s going on.

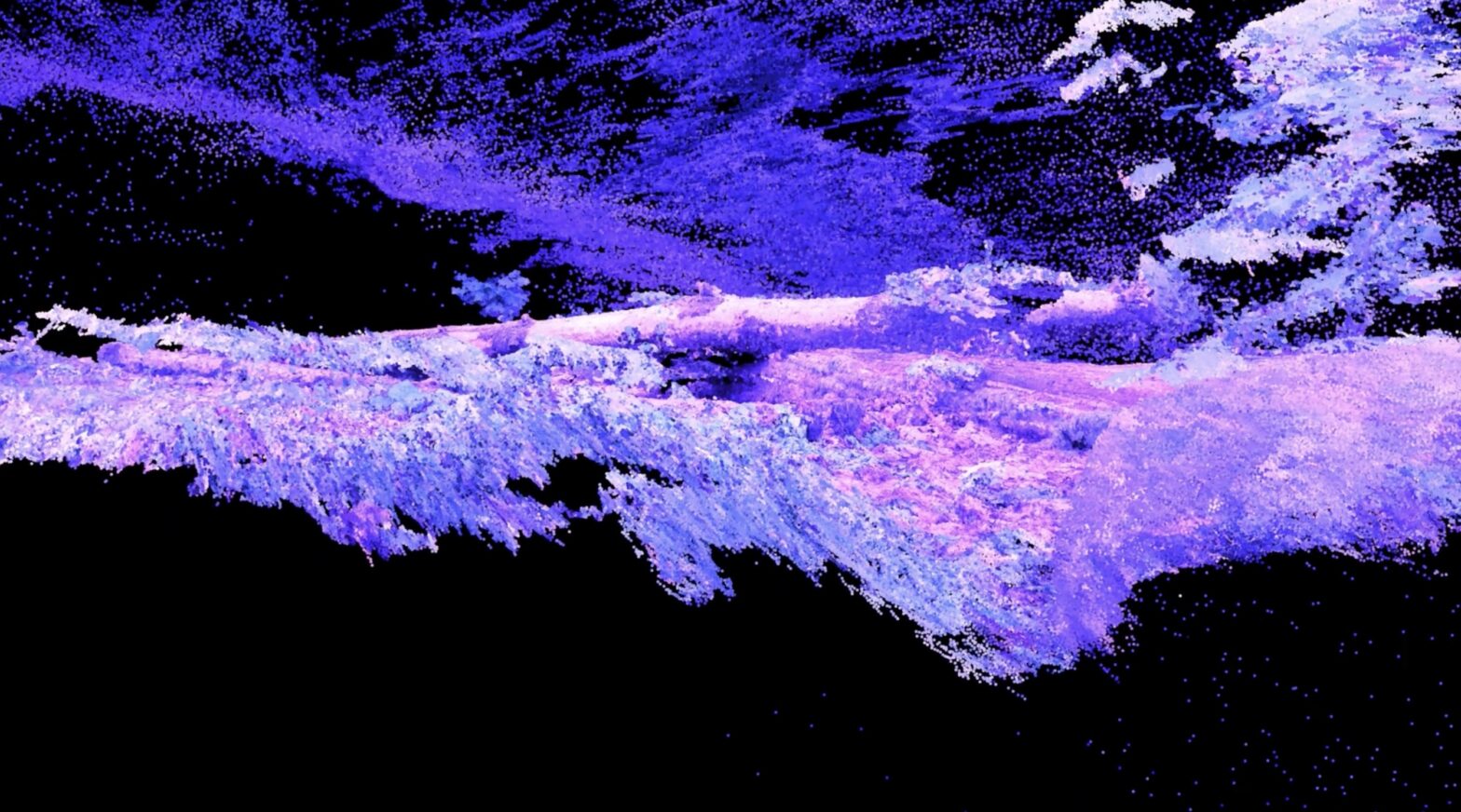

Thomas Lisle. Peaceful Co-Existence, 2023.

Art made consciously by humans vs AI art

The expectation of creating digital art without the need to learn the craftsmanship of sophisticated digital tools or to acquire visual skills is the biggest fallacy. You think that you have some control over what you have made with AI systems, but the truth is that you have none. If someone had made a similar artwork in software like Blender or Maya – I would be impressed, it would no doubt have taken much effort, and the end result would be made all the better through the time spent trying to make the visual effect and the time thinking about it. The big difference is that had it been made in Blender, the artist would be in full control of the artwork, every aspect of the image’s construction would be editable, manipulatable, and could be experimented with; it would be in 3D and not a 2D simulation, it could be built from the ground up by the artist who had some relationship with the tools he was using.

You think that you have some control over what you have made with AI systems, but the truth is that you have none.

But as an AI output, the artist hasn’t done anything other than ask a computer that knows nothing about humans to make an image or animation. The artist hasn’t painted anything, hasn’t sculpted anything, just typed in some prompts; the output may be interesting, but it has nothing of the artist’s hand or commitment, and I’d say consciousness in it. Who is to say whose images are being used to make this, and will it still be even legal in a few year’s time? It’s not legally copyrightable in the US as deemed not made by a human. It’s another case of asking an AI psychologist to help you with your problems. You are not learning anything about how to make digital art; you are just learning what instructions to use to make an image in a style which is not your own, which you could never make without years of learning, and if you did have those years of learning, it would be far better and far more valuable.

This is not art for the masses; it’s a mass delusion it seems to me. Only human consciousness and human intellect is relevant. A computer can’t be my therapist, nor can it draw my pictures for me; taking away these functions of humans enslaves us, imprisons us and strips us of our humanity. Across the board, individuality, the value and uniqueness of human consciousness, and free will are under attack from technology that gives the impression of offering freedoms, whilst at the same time eroding our privacy and selling our every online choice and decision to the highest bidder.

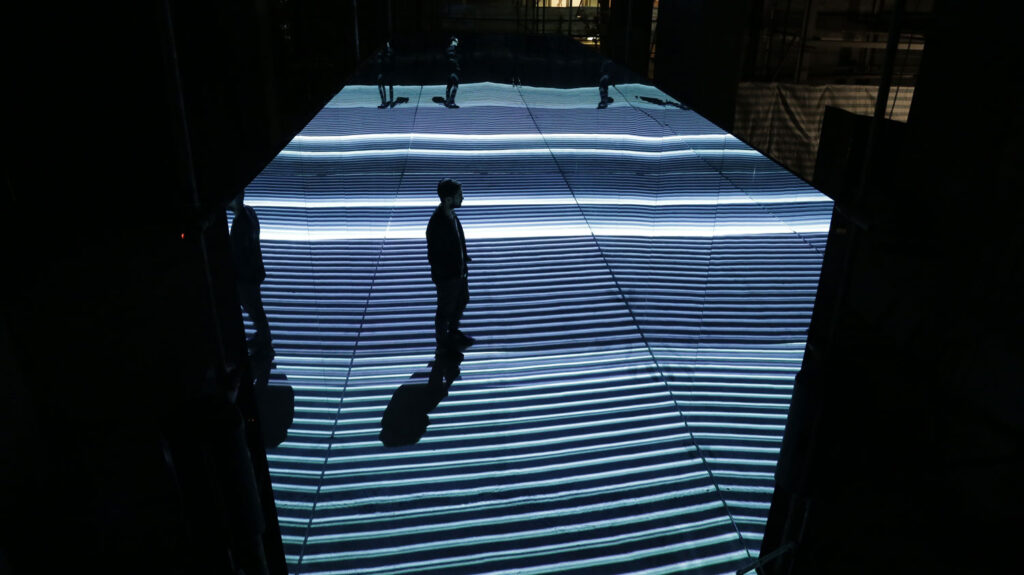

Thomas Lisle. Subconscious Motions, 2022.

Art made consciously by humans vs Generative art

My main concern with generative art is that it produces many multiple random compositions. They seem meaningless to me, maybe the original one has meaning but the subsequent random variations are not controlled by a human consciousness.

I think generative art, which produces thousands of random variations on a theme, is outsourcing the creative process, as glitch art does. Generative art uses code to independently determine an artwork that would otherwise require decisions made directly by the artist. It’s impersonal.

I do see the point of people making code to do something unique that’s human and creative; however, the results are often visually uninteresting, and the people making them often have no or very little art background (which is true across the board with digital art), no knowledge of the history of art, and no interest in painting.

Artists making generative art often have no art background, no knowledge of the history of art, and no interest in painting.

I will always remember the day in mid-1980 I showed one of my tutors from university, a dedicated hard-edge painter, how I made a square and a few circles on a computer. His first reaction was: “This makes a mockery of hard-edge painting.” And he was right. Really good hard-edge painting involves great composition, colour theory, and the patience and commitment to actually realise the work by hand in paint. It is no mean feat to make a canvas 5 x 5 metres in dimension- this was a big commitment – the hard work of making and realising the work over many weeks, compared to spending a short amount of time moving geometric shapes on a screen.

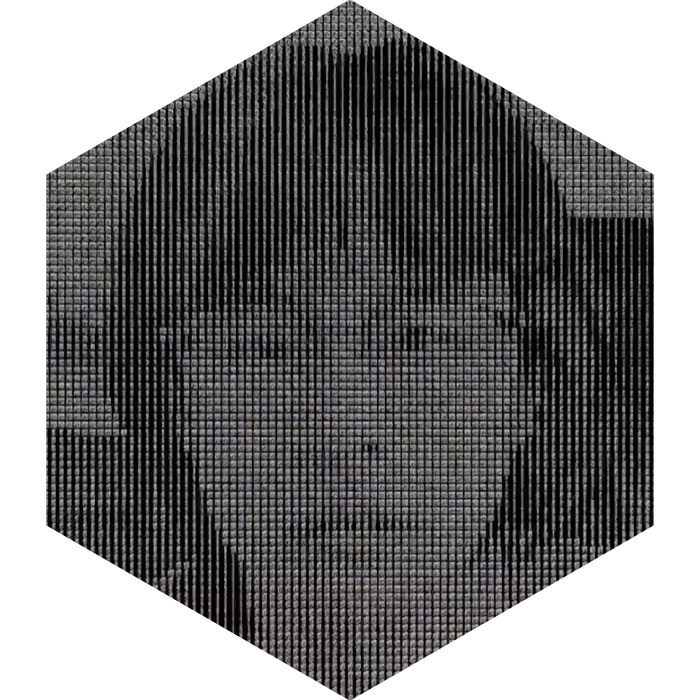

Thomas Lisle. Abstract 01, 2022.

Digital Art in Relationship to Contemporary Painting

How does the art of contemporary painters transition from the material to the virtual and time-based? I can only use my experience to answer this, and that is by finding ways to simulate paint and to incorporate painting using my hand as the basis of any paint stroke. I soon discovered that what flows out of a virtual digital paintbrush doesn’t have to be a liquid; in fact, to make a liquid simulation, I first need a model that defines where the liquid simulation comes out. That model is made by painting a model shape of a paint blob, which is animated by the movement of the hand and pen. Point, line and plane are actually the building blocks of all 3D models and systems, except they call the plane a polygon (still has to be flat) and the line a curve, as it doesn’t have to be straight and a point, a point or a vertex.

The Bauhaus got it right! It’s possible to link all sorts of data, like brush pressure, to different factors in the digital paint, such as width, enabling paint strokes which no longer look like traditional paint strokes. Mark-making also has a wide scope of possibilities. I like to use sort of squished-up hacked cloud simulations to simulate blobs of smeared paint. The analogies often get lost in the creation of new paint idioms. Everything is model based, Clouds, technically termed a ‘volume’, need a boundary that is defined by a model, which can be painted or sculpted.

The new possibilities of this technology are multiple and profound. Painting becomes painted sculpture and time-based painted sculpture.

The new possibilities of this technology are multiple and profound. Painting becomes painted sculpture and time-based painted sculpture. These are really fundamental shifts in the painting universe; where we have had hand-painted 2D animations in the past, we now have procedural 3D painting. Painting has never been 3 dimensional, nor has it ever offered so many possibilities. I see my digital 3D painting as fundamentally metamodern, firstly as a rejection of the impersonal, which has morphed today into the “no person”. As a rejection of deconstructionist ideas, it is more a reconstruction and reappraisal of all the most interesting aspects of abstraction and figurative abstraction. The integration of psychology into my work seems to me fundamentally a metamodernist approach to art. In terms of subject matter, psychology is, after all, the study of consciousness, of becoming, of how we live in the world and relate to it and how we do this personally and collectively.

Most artists using digital 3D are not using any painting; they are all modelling or using particle systems. The modellers make their own models or use models from the internet such as volcanoes, flowers, etc. They animate teh models by, say, rotating them or the camera that views them, to make a time-based artwork. Some artists abstract their models by manipulating and animating the points that form the polygons. The particle systems you see so many of are movements of points or large points that look like spheres driven by the maths of gas advection or by using random noise fields, basically using motion vectors to move particles through 3D space rather impersonal in my view. These artworks are not paintings, and there is no hand that has drawn/painted anything in them. They may have some visual relationship to painting, but that’s where the analogy ends.

The paintings of contemporary painters are not random and not sculpted and are rooted in the tradition of abstract art that spans over a hundred years. When I look back on 60 years of contemporary abstract painting in an objective way from Julian Schnabel, Albert Oehlen, Georg Baslitz, and Helen Frankenthaler, it’s really a bit of a random list of figurative and non-figurative painters. There is an important and passionate direction in their art to transcend the apparent, the photorealistic and the directly representative, which sounds like a definition of abstraction. There is an intellectual and personal journey of expression which broadly conforms with ideas or “thinking” of the time, a poetry of consciousness that can only be realised in a medium as flexible as paint and the hand and eye-to-consciousness relationship.

When I look at any artwork, I think primarily about its visual qualities and visual language. I initially set aside all conceptual ideas and technical craftsmanship and look at the piece solely on its visual qualities. I feel that an artwork should stand up on the basics first; it is, after all, a visual art.

Music that doesn’t have a good musical composition would not get listened to. In fact, music with random notes is difficult to listen to. Suppose the rhythm was wonky, having no merit whatsoever, made by someone like me, who is tone deaf and knows nothing about music except how to enjoy listening to it. Randomness, lack of structure, and disregard for traditional ways of doing do not necessarily equate with groundbreaking innovation.

If you don’t understand the principles of form, visual rhythms, and colour, then it shows in the artwork.

I like a very wide range of music from baroque to trip-hop. Even in the most cut-up, remixed, mangled trip-hop music, the rhythm, beat, and groove hold it together; it often reminds me of an Albert Ohlen painting. My point is that most music has structure and composition, holds together as a whole, follows the basic rules, and builds depth in dynamic new ways built on strong basics of musical concepts. The same is true of visual arts: if you don’t know the basics or can’t make basic compositions, if you don’t understand the principles of form, visual rhythms, and colour, and you don’t know anything about art history and how contemporary art evolved, then it shows in the artwork.

To me, the composition is the groove in art from Piero Della Francesca to Terry Frost to Titian to Gillian Ayres.

There doesn’t seem to be a natural progression for this type of art in the digital world as yet, and I think that’s partly due to the complexity of the software. But it’s super easy to do other stuff that looks interesting. There are all sorts of ways to do something similar to Maya in Blender, which is free.

Thomas Lisle. Abstract 02, 2022

Metamodernism

There is no clear definition of metamodernism yet. This term refers to a heightened sense of cultural, philosophical, psychological, and political awareness that draws on the past and the present, bringing more information to give better solutions and understanding of consciousness and reality. A catchall for people rethinking the world.

If postmodern values are built on modernist values, then metamodern values are built on postmodern values in a general sense. Metamodernism has also been called “deconstruction deconstructed.” Metamodernism tries to sort out the issues which postmodernism doesn’t deal with, such as empathy, sustainability, equality, alienation and universality.

Why are the arts important, and why do we make theories about art? Because art is the most important way to understand the world, people, and ourselves. Meaning in life is under attack. Metamodernism is perhaps a tool for finding meaning.

One way I like to think of metamodernism is, as philosophy and thinking in therapy, “So post-modernist thinker, when did you realise it wasn’t working, that things needed to change? Well, I heard these sounds coming from behind the shopping mall walls. And how do you feel about that now? I’m missing something?”

If I have a criticism of metamodernism, it is that it’s almost totally Western thinking-centric; there are no references to non-Western thinkers, who I feel have already covered some of the topics of the metamodernists and post-modernists. Comparative philosophy needs more inclusion, the writings of Toshihiko Izutsu are wonderful and enlightening, and although writers like Julian Baggini, have only just started to write about comparative philosophy, his book How the world thinks is a great introduction. Integral Theory, a building block of Metamodernism does start to take this into account. The Leading Edge Of The Unknown In The Human Being, a talk by Ken Wilber, is a powerful global framework for comparing world ideology.

There seem to be universal physiological structures, universal philosophical themes such as existence, how do I live my life, consciousness, and even universal language models are starting to appear with AI research from the ESP foundation; we are all more connected than we ever thought before seems to be an important building block of metamodernism.

Digital technology and figurative abstraction

This is one of the most complex and rich visual abstraction possibilities of digital 3D. Firstly, it’s possible to take a model of a person, abstract or non-abstract, and apply the motion of another human captured digitally to your model. This in itself is quite interesting, and it’s equally possible and perhaps more creative to animate the figure yourself. This makes a base layer or canvas model upon which to paint in 3D. The paint moves with the motion capture data. You can turn off the visibility of the canvas model below and then just see your painting.

This is a totally new way of looking at abstract figuration, which opens all kinds of new possibilities that were unthinkable ten years ago.

Abstraction

I grew up and became interested in abstract art when I was about 6 or 7. I was never really interested in drawing in itself – it seemed to me that that era had passed. I love and admire great drawings and draughtsmanship, but like music, which is all abstract, I think art needs to reflect internal processes, ideas and concepts, reality abstracted.

Reality is not flat. I think the first computer-like 3D abstract face was made by Duhrer back in the 15th Century. You can see Picasso taking a real interest in 3D abstraction, especially in the 1930s and 1940s, even 3D tubular lines. As an artist, I don’t want to and can’t emulate Picasso. To me, it seems that he strived for a deep and meaningful level of abstraction, his abstraction is three-dimensional in a great deal of his paintings. In other words, it looks 3D but it is 2D in paint. I love German expressionism but it has a very different approach to figurative abstraction and doesn’t think in 3D terms very much; you could say it’s gone out of fashion, and it’s probably harder to do especially if you want to paint a bad picture. However, trying to make abstract figurative art in 3D makes you realise Picasso was pre-empting the digital possibilities of today. As soon as you start abstracting digital 3D figures, you’re reminded of his work.

Look at Glitch art: in the 1990s, it was difficult to get the technology and difficult to make. Today, every art student has access to the Adobe Creative suite, where they can use hundreds of templates with After Effects to make Glitch effects. Now it’s mainstream.

Why is the history of contemporary art important?

Technology aside, it is the journey of the artwork and artist in developing abstract art that is also essential. If you don’t learn how to make something, and you just have to type “make me an elephant flying in the clouds with thousands of balloons, in an abstract style”, I have a lot of issues with it as art to be taken seriously.

While it’s great that so many people are finding pleasure and fascination in making digital art, and it’s super easy to do all sorts of fun things, I think it’s really important to understand some key things about making art digitally.

If you don’t learn how to make something, but just type a prompt, I have a lot of issues with it as art to be taken seriously.

Technology and art

It is essential to understand what digital artists are doing; if you think someone has painted something when they have just given a prompt to a computer to “make a black square”, it would be many miles from the truth.

It’s difficult to evaluate something if you don’t know anything about it; however, from a visual perspective, the same principles apply to a digital work as they do to contemporary painting and sculpture, except when the artwork is time-based, then there is much less history behind it.

The number one key factor I apply to all digital and video effects –well, it’s also important to understand the difference between the two– is, “Is this visual effect? I’m looking at something unique, something handcrafted and to what extent is it handcrafted? I think nowadays; nearly everybody is using blocks of code that have been developed by someone else to some extent and then reusing this code in some way, or the code they are using is in some way just a tool to let you do something.

For example, I use a visual programming language called Bifrost inside the 3D software Maya. A team of people have built the tools that let you manipulate procedurally the fundamentals of form, movement and colour. The artist controls how it works by programming through nodes, which act as modular lumps of code that do very specific functions and tools, basically.

If you don’t know anything about what is available off the shelf for video, 2D or 3D graphics, then it’s difficult to evaluate any artwork, in the past you couldn’t photocopy a Richter painting and say it was yours. But one way is to see if the artist talks about their process, as in most cases, if they don’t, they haven’t struggled to develop anything unique but are just starting on the path of learning digital technology. It is by no means an accurate way to evaluate the technical craftsmanship of an artist! But it shows some intent.

When you think about, say, Albert Ohlen talking about his painting, where he describes the process as being all on the canvas, there’s nothing hidden. I would say the same is true for much of digital art, but that’s because I know the capabilities and technology extremely well, having been working as an artist, a freelancer and a consultant in this field for 40 years. It’s not surprising curators or art galleries, even digital art specialist galleries, don’t know much about it. It’s just not as simple as pencils and paint, which everyone has some experience in and can see where the skill lies.

It’s not surprising curators or art galleries don’t know much about how digital art works. It’s just not as simple as pencils and paint.

There are hundreds of years of art criticism and evaluation to draw upon for the evaluation of drawings and paintings. In today’s world, that all tends to get thrown out the window, and when so few people actually are able to paint or draw in time-based digital media, then that exacerbates the problem. Directly drawing and painting in 3D is really not that common; it’s not something that is used much in feature films, websites, and corporate videos, and as such, it has been sidelined by software developers. There is a free Google VR headset software that lets you paint in 3D, and you could also do it in Blender, I believe. I think Maya is the only professional software package that has a paint system that is incorporated at the base level into all the other features and tools that Maya offers. This means 3D paint output can be easily incorporated into all the other systems in Maya.

Time-based abstraction

Digital art offers artists the ability to make abstractions in ways that are simply beyond the possibilities of traditional painting, yet keep the plasticity of paint, by plasticity, I mean the ability to depict and represent anything. Digital art can only compete or match this plasticity in 3D. Yes, you can probably paint something 2D in software like “Painter,” it will not automate anything for you; it won’t animate it or make it procedural, and it will take thousands of paintings to make 10 seconds of animation. The real revolution is in 3D, where your creation is in 3 dimensions as opposed to 2D; however, this doesn’t stop it from being painted or using 2D images, which are manipulated in 3D. If you build a realistic head in an application like Zbrush, it can look amazingly realistic, yet it can also be viewed from any angle.

Digital art offers artists the ability to make abstractions in ways that are simply beyond the possibilities of traditional painting

The big problem for painting and abstract art is how to make it time-based. This is clearly the next development for painting and sculpture. Making a painting time-based by animating it by painting each frame 25 times per second makes it laborious beyond belief and would test the endurance of most artists, i.e., spending a year making 5 seconds of animation is just impractical. And here is where we have to thank Hollywood and the need to make impossible things look realistic and be time-based, from explosions and aliens to lava, hair cloth and humans, and the billions of dollars spent developing these technologies, as the art world would never have done so. In fact there are so many different things in the real world and multiple imaginary universes that the software that engineers built to achieve these goals became totally modular and interconnected so that it could meet the needs of an industry that might want characters made of sand or glue or leaves, etc. They expose and allow the accurate manipulation of 3D models at the pixel and voxel level, the atomic level of an image, you might say, or the smallest drop of paint or finest particle of marble, to put it in traditional terms.

But that is just the start because instead of just being able to control each drop of paint, they have built systems to control great swathes of drops of paint or the equivalent and laid bare all the parameters and code – made it so that artists, in the wide sense of the word, can animate and abstract forms, be they paint strokes, characters of sculpted objects easily and quickly.

When you make software that can make anything visually, you have tools that contemporary artists can make use of to make contemporary art.

We are probably at the stage where we have the tools to make most contemporary paintings, the only thing holding artists back is computing power. However, a great deal can be done on a computer of a few thousand pounds, as the developers have built workflows to get around slow computer limitations.

Abstraction without any structure and composition doesn’t seem to work for me, and I often think of Jung’s theory that some paintings are just empty, and it is viewers who fill them with meaning. I think Jung is implying that the painting is basically empty and impersonal. I know that when I make abstract paintings that rely on just form and colour, it can be difficult to pin down what it’s about and I can sometimes give a painting ten different titles all of which might fit. I was reading Albert Oehlen’s talk about Richter’s new paintings, and he was saying that the squeegee paintings that Richter makes are like Richter has given up trying to make compositions or meaningful art. I would wholeheartedly agree. They may be rich and colourful, but there’s no meaning, no structure, no narrative.

My time-based abstract painting aims to be quite different; each element moves, transforms, deforms, evolves, devolves, coalesces, or oozes with a purpose and tells a story, has a narrative. It is a process. Sometimes I see my work as mental processes in the abstract, not mine in particular but the universal. Think of the decision-making process of something difficult you need to decide on, there will be a host of influences pulling you in multiple directions. If there were none, then the decision-making process was not difficult. This is going on throughout our daily life on big and small issues, over long and short periods of time, then think of all these factors as abstract forms, it probably doesn’t look anything like my paintings! But it hopefully gives an idea of the thinking behind the work. You could see it as painting the subconscious, which is way more complex than simple decision-making. My point is that time-based painting is totally different to non time based painting.

In my own work it becomes very apparent to me that time-based paintings are much more expressive than static ones. I put this down to the fact that Psychology and consciousness are not inanimate, not 2D, but dynamic and as soon as an artist makes a mark that has a life of its own, the viewer looks and thinks about it in a different way.

Painting

A painting can only be made by using your hands with or without a brush or something to make marks on a surface or in 3D. The definition of a painting needs hands, humans and perhaps a tool. It’s a human expression from mind and eye to hand. Typing/generating code to create a square is not painting! Applying a filter to some video footage is not painting, algorithmically generating shapes is not painting, scanning an object in 3D is not painting, and making images without the hand-to-eye relationship is something else.

Painting needs hands, humans and perhaps a tool. It’s a human expression from mind and eye to hand. Typing/generating code to create a square is not painting!

If there isn’t any actual painting involved, then it’s not a painting. It’s something with some reference to painting in some way or the other. Hard-edge painters like Frank Stella still made them by painting them.

Animated models and character animations code constructed cubes, particle animations driven by mathematical fields, calling any of this type of art a painting is as silly as taking the text of this essay and calling it a painting in black and white. I have seen some really good work by digital artists that has some kind of visual language and relationship to painting, but they are not paintings.

My key points are that art theory on point line plane, composition, and colour from the Bauhaus onwards is still relevant. Painting is still relevant, even if you take the act of painting out of a visual artwork as most digital art does – you can’t take the understanding of composition, form and colour out. You can’t take the artist out of the equation. You can’t take art history away and pretend it doesn’t exist, unless, of course, you don’t know anything about it in the first place.

Poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity.

Audre Lorde

Time-based art

Under cover of the digital art umbrella, what is going unnoticed is that the vast majority of contemporary digital art is time-based, and this is a fundamental shift in thinking and working practice for artists, especially for artists who were painters, as time-based painting doesn’t really exist much.

Time implies that there is a narrative, a progression, a process, a story, or all combined. Painting up until this time had evoked movement, been called capturing movement, even called dynamic, but it was all static. There is a fairly long history of artist filmmakers and artists who made animations, some with paint. I can only think of a very few artists working in animation who actually painted every frame. Digital painting does away with the tiresome need to paint every frame through procedural procedures, these procedural techniques can apply to computer-generated cubes, artist-sculpted flowers, or library models of humans.

Time implies that there is a narrative, a progression, a process. Painting up until this time had evoked movement, but it was all static.

There seems to be an array of different narratives for artists to draw upon:Abstract narrative, process narrative and figurative narrative. All offer a new and profound change in how art is perceived.

3D painting

The funny thing about 3D painting is that as soon as you make it, it’s a sculpture! And as soon as you animate it, it is telling a story, it’s got a history.

There are four fundamental types of 3D painting:

- One is the single tube, which can vary in diameter.

- Two are multiple tubes together, which can start to look like a loaded realistic brush stroke. These are especially interesting, as it’s possible to procedurally manipulate how all the strands behave, if they stick together or not, for example.

- Three is where either of these previous two types of brush stroke is used as an emitter of a liquid of a fluid or goo.

- Fourth is where the first two types of brush strokes are converted into clouds, or cloth simulations, or particles, or any number of other types of procedural effects and the base form is made through painting.

Let’s not forget sculpting. I don’t use Zbrush, but it is by far the most sophisticated 3D modelling tool out there I’m not sure it lets you animate your model. Maya and Blender have sculpting ability which are animatable.

All the painting types I just listed are basically 3D forms and, as such, are sculptures. I think it’s safe to say that time-based sculptures can, on the whole, be called sculptures as you can send them to a foundry and have them cast, a 3D painting is a sculpture as well.

3D paint, which is a fluid emitter, can have all sorts of procedural forces applied to it, it’s also possible to adjust gravity up or down or to animate it over time, every aspect of the fluid can be abstracted and animated over time.

I tend to work in two very different ways: I either think I’m going to make a still image that I turn into a painting, or I make an animation that I see as being time-based. Recently, I have been making physical paintings that I might make into animated digital paintings. I see a very clear difference between a still image and a moving image and a very different way of working and organising what I do.

Thomas Lisle. “Something Stirs,” 2023

My art history

I was maybe the first person to invent glitch video. I thought it was a great way to abstract images in time to make images that look like paintings. I made videos and large-scale installations using glitch video, instead of going into art education for an income, as there was no real income stream for digital contemporary art at the time.

I got freelance jobs and also worked closely with Apple Computers UK. I worked as a digital video graphics consultant as a way to learn in-depth about digital technology and use all their kit, which I couldn’t afford. By the mid-1990s, I knew all the major digital graphics 3D and video software and how to use them, and I taught TV production companies how to use them. I have seen these software systems develop and grow over the years, and new ones emerge. I worked in the broadcast video, architectural, graphic and interactive design sectors for a while.

Why is digital 3D the most important technology

In 1990, I quickly realised that the technology which offered the most exciting possibilities and opportunities was 3D. It’s a kind of synthesis of 2D and 3D and time-based visual sensibilities. 3D offers perhaps the current pinnacle of what is possible on computers and is the basis of film effects AR and VR – it’s all just 3D viewed and computed in different ways. What has super boosted this technology is the film and games industry. Suddenly, people realised that games and VFX in film meant big buck profits, and this feedback led to the development of cool software.

Having taught lots of people how to use 3D in the past, I realise that it’s hard to learn. There is a huge amount to learn and get your head around. There are off-the-shelf effects in 3D animations, too, but the creative part of the craftsmanship comes in understanding the techniques you are using and using them in the way you want. The great majority of people working in film FX professionally can look at any 3D effect and can easily break it down.

My art

I see a strong relationship with art and psychology on a broad spectrum, and I enjoy discovering the rich and diverse world of the human psyche.

The more I learn about Metamodernism the more I discover its deep relationship with psychology.

Understanding ourselves, our motives, our conditioning, seem to me to be the keys to unlocking a better society, better art, better environment, better thinking.